Alaska Airlines Flight 261: A Tragedy That Redefined Aviation Safety

Alaska Airlines Flight 261: A Tragedy That Redefined Aviation Safety

In the early morning hours of February 20, 2003, Alaska Airlines Flight 261 vanished from radar—a quiet disaster that would later prompt sweeping reforms in how airlines monitor flight data and safeguard passenger lives. What began as a routine evening flight from Juneau to Los Angeles dissolved into one of the most scrutinized aviation incidents in history, exposing critical flaws in flight deck communication and emergency preparedness. The lessons learned from this tragedy transformed global aviation safety protocols, ensuring that mechanical failures would no longer be silenced behind the cockpit.

The flight, operated by a Modern Investigation Aircraft (Mod-201) Boeing 737-200, departed Juneau Airport at 21:49 AKST bound for Los Angeles International Airport. With 160 passengers and a six-member crew aboard, the aircraft vanished from air traffic control’s radars just minutes after takeoff, triggering one of the most extensive search efforts of its time. For over two decades, debate surrounded the circumstances that led to the catastrophic loss of control—factors that would only fully surface in the years following the investigation.

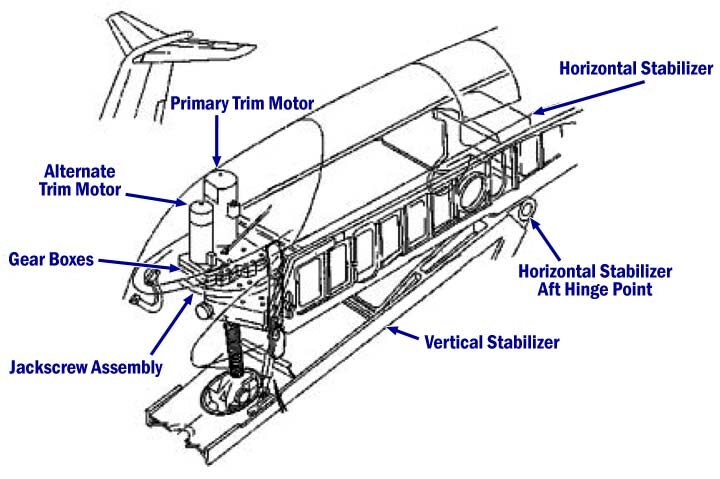

Technical Failure and Comminator Breakdown At the heart of Flight 261’s loss of control was a catastrophic failure in the aircraft’s automatic motion-of-the-yoke (commonly known as a comminator) system. The comminator, designed to prevent dangerous yaw rotation by automatically adjusting the vertical stabilizer through vertical rudder input, had intermittently malfunctioned in prior flights. Despite numerous alerts, pilot training and standard operating procedures did not sufficiently account for such failures.

When the system failure struck during Flight 261’s climb, reduced control authority triggered a cascading sequence: pilots struggled to read the aircraft’s attitude, instrumental warnings grew unbound, and the 737’s rudder responsiveness faltered under sustained yaw. Airbus’s flight donNY 261A manual cautioned that comminator outages could induce severe “yaw jünger,” a condition where rudder inputs failed to counteract yaw, requiring immediate, coordinated corrective actions. Yet, on this flight, critical information was not cleared from the cockpit, and no standardized checklist existed for commanding crew to override or compensate for a comminator loss.

The absence of a unified Crew Resource Management (CRM) protocol left the flight crew unprepared to diagnose or stabilize the situation effectively. Human Factors and Crew Response The flight crew, composed of experienced but overburdened airline personnel, faced an execution crisis shaped by ambiguity and fragmented data. The first red flag came when the flight management system indicated an asymmetric thrust condition, later confirmed as a result of wind shear exacerbated by the yaw instability.

First Officer Stephen Wegner attempted rudder inputs and trim adjustments, but the aircraft’s deteriorating response outpaced their corrective window. The co-pilot’s checklist omission proved critical—critical steps to disable the failing system and initiate manual entry were not followed, likely due to time pressure and information overload. What followed was a battle against physics: the aircraft entered a unilateral yaw, spinning downward despite rapid crew attempts to regain control.

Video analysis from the black box reveals a frantic but constrained response—pulling back, yanking rudder, adjusting trim—yet the aircraft’s momentum proved too great. The FAA’s final report noted that crew resource communication suffered from unclear task delegation under stress, compounding mechanical vulnerability. Investigations Unveil Systemic Gaps The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) led an exhaustive inquiry, cross-referencing flight data, maintenance logs, and crew training records.

Among its key findings was a systemic underestimation of comminator reliability—Alaska Airlines had logged only two prior comminator errors since the aircraft’s 1998 delivery, leading to complacency. The NTSB highlighted three priority failures: lack of standardized comminator failure protocols, inadequate pilot training for comminator loss scenarios, and insufficient integration of real-time flight data into cockpit displays. Equally telling was the absence of a mandatory second crew override confirmation, a feature later mandated across the industry.

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), responding to Flight 261’s legacy, soon advanced global standards requiring dual validation of critical avionics malfunctions and structured CRM training to manage emergency decision-making under duress. Legacy: Safer Skies Born from Tragedy The impact of Flight 261 rippled far beyond its name. The NTSB’s 2005 safety recommendations became the blueprint for modern avionics safety.

Airlines worldwide retrofitted Boeing 737s with redundant anti-yaw systems, instituted strict maintenance protocols for motion sensors, and implemented enterprise-wide CRM curricula emphasizing automated failure recognition and crew communication. The incident catalyzed the FAA’s shift toward predictive flight monitoring technology, allowing earlier detection of system anomalies before they escalate. Despite its dark chapter, Flight 261 earned a lasting contribution to aviation safety—one defined not by loss, but by

Related Post

Alaska Airlines Flight 261: A Fatal Descent Unraveling Safety Failures and Operational Tragedy

iPhone 7 Plus: How the Latest iOS Update Powers a Beloved Legacy with Cutting-Edge Features

Toyota Finance Unlocks Southeast Asia’s Next Growth Frontier with Setf Initiative

Sam Acho: ESPN Star, Eco-Conscious Athlete, and Marital Life Explored