Charles’ Law Unveiled: How Temperature and Volume Dance in Perfect Equilibrium—And Why It Powers Modern Industry

Charles’ Law Unveiled: How Temperature and Volume Dance in Perfect Equilibrium—And Why It Powers Modern Industry

At the heart of thermodynamics lies a foundational principle that governs the behavior of gases: Charles’ Law. This scientific cornerstone describes the direct relationship between the volume of a gas and its absolute temperature, holding pressure constant. Formulated centuries ago by Jacques Charles, the law remains indispensable in engineering, meteorology, and countless industrial applications.

From weather balloon trajectories to refrigeration systems, Charles’ Law explains why gases expand when heated and contract when cooled—behavior so predictable that modern technology relies on it daily.

Charles’ Law states: At constant pressure, the volume of a gas is directly proportional to its absolute temperature (in kelvins). Mathematically, this is expressed as V ∝ T when P is fixed.

Translated into modern scientific notation, the formula becomes V₁/T₁ = V₂/T₂—a deceptively simple equation that unlocks precise predictions about gas behavior under thermal change. This proportionality reveals a fundamental truth: temperature and volume are not independent; when one rises, the other expands, provided external pressure remains unchanged.

To fully grasp Charles’ Law, one must first understand absolute temperature. Unlike the Celsius or Fahrenheit scales, absolute temperature must begin at zero—absolute zero—where molecular motion theoretically ceases.

The kelvin scale, defined by absolute zero at 0 K, ensures mathematical consistency. When converting temperatures for Charles’ Law calculations, shifting to kelvins prevents erroneous results. For instance, a temperature of 27°C (300 K) and 57°C (330 K) reflect the same thermal state when expressed in kelvins: V₁/300 = V₂/330.

The lambda in physics—ΔV/ΔT = V₀/T₀—captures the essence of Charles’ Law: a change in volume (ΔV) is proportional to a change in absolute temperature (ΔT).

This linear relationship enables engineers to design systems that manage gas response to heat with precision. Unlike gases governed by more complex equations, Charles’ Law applies strictly to ideal gases under reversible and isobaric conditions—making it both elegant and robust in controlled settings. “The law’s simplicity is its greatest strength,” noted Dr.

Elena Torres, a thermal scientist at the Institute of Applied Thermodynamics. “It provides a clear, testable model that underpins countless real-world innovations.”

Historically, Jacques Charles first observed the volume-temperature relationship in the 1780s using self-made gas-filled spheres. Though later refined by Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac and formalized by Émile Charles—after whom the law is named—Jacques laid the empirical groundwork that remains central to gas law documentation today.

The formal equation V₁/T₁ = V₂/T₂ emerged from meticulous experimentation, proving temperature and volume are not merely related but fundamentally interconnected in gaseous systems.

In industrial practice, Charles’ Law governs critical processes ranging from pipeline conveyance to HVAC system design. Consider natural gas transportation: pipelines must account for seasonal expansion—cold winter air causes gas volume to contract, reducing flow pressure, while summer heat triggers expansion that increases internal pressure. Engineers use Charles’ Law calculations to design expansion joints, pressure relief valves, and flow regulators to prevent emergencies.

“Without understanding how temperature shifts volume, pipelines could rupture or underperform,” explains Mark Delgado, senior piping engineer at National Gas Holdings. “It’s not just theory—it’s safety and efficiency in motion.”

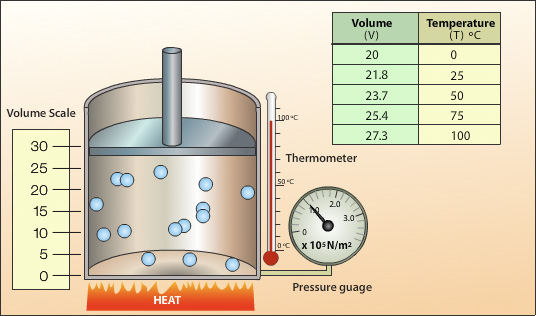

Another vital application appears in laboratory settings. Gas measurement devices like water displacement rigs and digital manometers depend on Charles’ Law to interpret volume changes under controlled heating.

In education, the law is a proving ground for thermodynamics students, where visual demonstrations—such as balloons inflating in a warm water bath—make abstract principles tangible. These real-world examples reinforce why Charles’ Law isn’t confined to textbooks—it’s alive in the machinery that sustains modern infrastructure.

When working with Charles’ Law, careful attention to units and conditions is essential. Temperature must be in kelvins; pressure must remain constant; and the gas must approximate ideal behavior.

Deviations occur under extreme pressures or with real gases that exhibit non-ideal characteristics, particularly near critical points. Nonetheless, in ideal or near-ideal scenarios, the V₁/T₁ = V₂/T₂ relationship delivers reliable, repeatable predictions—qualities prized in engineering calculations. “Accuracy begins with proper assumptions,” warns Dr.

Torres. “Using absolute temperature in kelvin ensures the proportionality holds, avoiding costly miscalculations.”

Broader impacts extend into environmental science. Weather balloons, for instance, expand as they ascend into colder upper atmospheres due to climbing temperatures.

Without Charles’ Law

Related Post

Alert Oriented X 3: The Next Evolution in Proactive Threat Response

Lisa Mesloh: The Life Behind the Scoreboard — Wife, Mother, Golf Enthusiast, and Family Pioneer

Shielding the Diamond: The Precise Positions, Initial Setup, and Essential Roles in Baseball

Rudy Pankow Age Unveiling the Rising Star of Hollywood That’s Redefining the Industry