Chemical Changes That Shape Everyday Life: From Toast to Tea — The Invisible Science Behind Common Moments

Chemical Changes That Shape Everyday Life: From Toast to Tea — The Invisible Science Behind Common Moments

Everyday life is a continuous theater of chemical transformations that unfold without fanfare—often unseen, yet foundational to how we experience the world. From the moment bread is toasted to crisp perfection to the hot cup of coffee awakening our senses, chemical changes are quietly at work, altering matter at the molecular level to deliver familiar comforts, flavors, and conveniences. These transformations—defined by the breaking and forming of chemical bonds—are not abstract laboratory curiosities but active participants in morning routines, cooking, cleaning, and even self-care.

By examining five defining examples, we uncover how simple chemical processes sustain and enrich daily existence.

1. The Heat of Toasting a Slice of Bread: Carbohydrate Transformation

The crispy, golden edge of toasted bread is more than a textural delight—it’s a textbook example of the Maillard reaction, a non-enzymatic browning process where heat and amino acids react with reducing sugars.When bread is exposed to high temperatures, such as in a toaster or griddle, complex molecular interactions trigger profound changes. Sugars caramelize while amino acids from the wheat proteins catalyze reactions that produce hundreds of flavor compounds and aromatic molecules responsible for that rich, toasty aroma. Though no atoms are lost, the chemical structure of the original bread sugars and proteins is irreversibly altered—demonstrating how thermal energy drives transformation without changing a substance’s molecular weight, but dramatically shifting its sensory quality.

“The moment bread turns golden, it’s not just browning—it’s a symphony of chemistry,” explains food chemist Dr. Elena Marini. “The Maillard reaction converts starches and proteins into compounds that deliver flavor, color, and aroma, turning a simple grain into a complex, delicious experience.”

2.

Brewing Coffee: Complex Reactions Behind Every Sip Coffee consumption offers a vivid illustration of the chemical diversity triggered by heat and water interaction. When water extracts compounds from roasted coffee beans, a cascade of reactions unfolds. Roasting initiates caramelization—sugars breaking down into aromatic molecules—and pyrolysis, where heating primes cellulose and lignin to release volatile compounds.

During brewing, solubilization draws out chlorogenic acids, caffeine, and fatty acids, while further reactions between amino acids and sugars generate hundreds of flavor constituents. Even the bitter notes mask nuanced sweetness born from precise chemical shifts. As chemist Dr.

Raj Patel notes, “Coffee’s profile is a chemical fingerprint made in the bean, water, and heat—no two batches taste alike due to subtle variations in these reactions.”

3. Cooking an Egg: Denaturation Transforms Raw to Set

The transformation of liquid egg to tender yet firm custard is one of the most visible and familiar examples of protein denaturation—a chemical change driven by heat. Raw egg contains fully folded, three-dimensional protein structures held together by weak bonds like hydrogen bridges and hydrophobic interactions.As heat destabilizes these bonds, the proteins unravel and re-form into a denser network, trapping water and creating a solid texture. This unfolding and realignment marks a definitive shift from liquid to semi-solid, visible even before cooking begins. The process doesn’t involve breaking peptide bonds—preserving the amino acid sequence—but the structural reorganization is irreversible.

This same principle applies to cooking other proteins such as milk curdling in yogurt or meat fibers tightening when seared. “The science of cooking hinges on understanding these molecular rearrangements,” says chef and food scientist Maya Thompson. “When you cook an egg, you’re literally reshaping its internal architecture—turning fragile proteins into a stable matrix that retains moisture and creates texture.”

4.

Browning an Apple: Enzymatic Oxidation at Work The quick brown edge on an apple slice isn’t just caused by heat—it results from enzymatic oxidation triggered by exposure to air. Enzymes called polyphenol oxidases act on phenolic compounds naturally present in apple tissue when cellular damage releases both enzymes and substrates. Upon contact with oxygen, molecular oxygen and these enzymes catalyze phenolics into quinones, which polymerize into brown melanin pigments.

This oxidation, though chemical, proceeds rapidly at room temperature and halts if cooled—preserving the fruit’s crispness for minutes. “This browning is a defense mechanism,” explains botany researcher Dr. Fiona Clarke.

“It makes the fruit less appealing to pests while signaling ripeness—but the process is purely a chain of oxidation and polymerization, rooted in biochemical control.”

5. Brewing Steam: Condensation and Expansion in Gas Phase Shifts

Great steams rising from a kettle are not merely vapor—they represent a daily showcase of condensation, a phase change driven by chemical and physical principles. Water molecules at boiling point absorb heat, transitioning from liquid to gas.Yet those escaping air don’t remain invisible; as they rise into cooler air, they condense into tiny droplets through intermolecular attractions. The water molecules reorient from a disordered liquid state into a structured,

Related Post

Are Rob And Dan Schneider Related? Uncovering the Family Ties Behind a Media Dynasty

Alfalfa Little Rascals: Pioneers of Early Childhood Learning Through Humor and Play

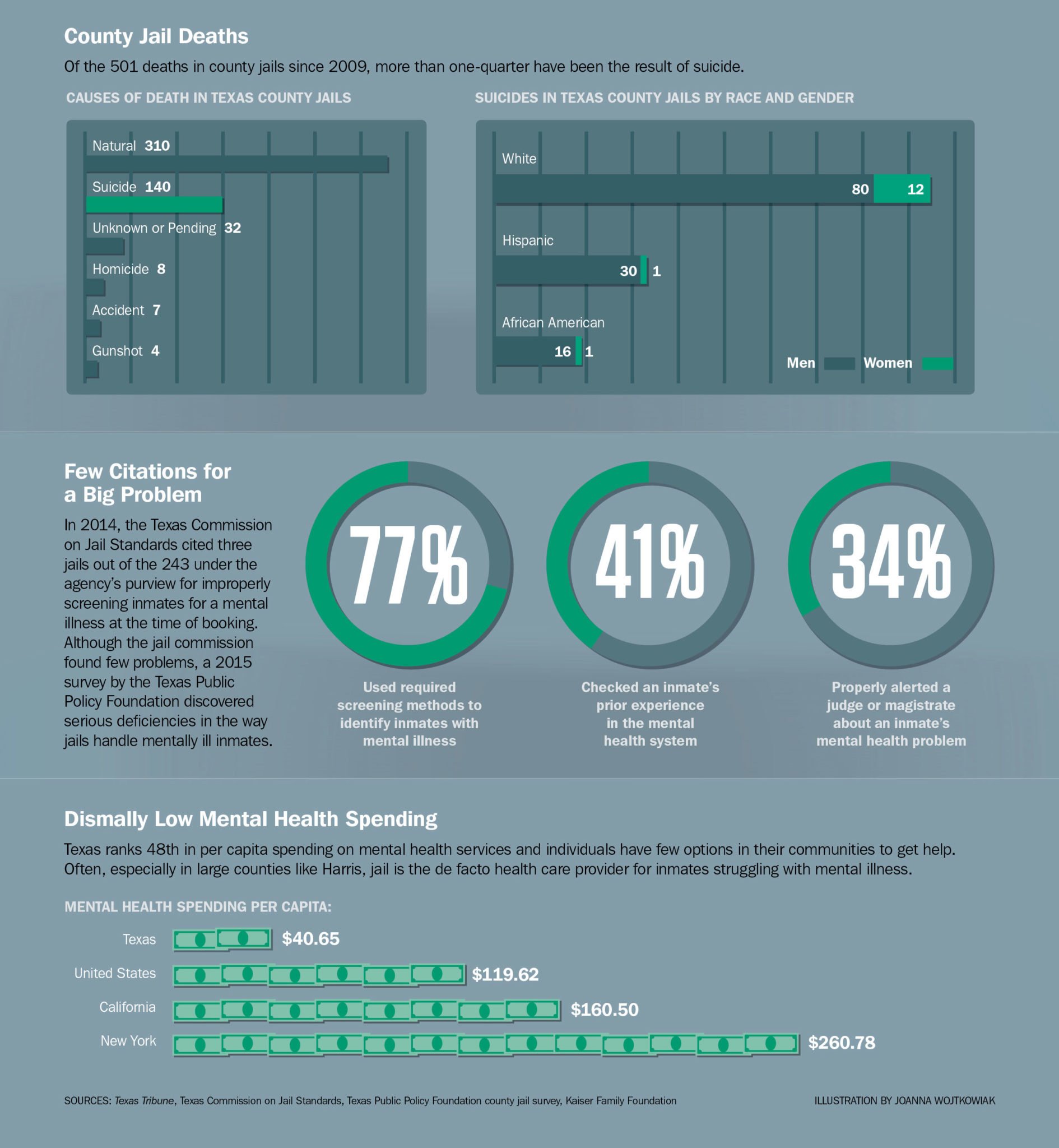

Prisons In The Netherlands: Answering Your Top Questions About Justice, Reform, and Reality Behind Bars

Jennifer Love Hewitt: From Dance Shows to Daring TV Roles—The Evolution of a Versatile Star