Decoding Acid-Base Lab Mastery: How Identifying Selected Anions Transforms Diagnostic Precision

Decoding Acid-Base Lab Mastery: How Identifying Selected Anions Transforms Diagnostic Precision

<

pH imbalance in patient samples triggers a chain of analytical decisions, where selective anion identification serves as a diagnostic compass. “The anion hole,” a fundamental concept in clinical chemistry, exemplifies this: a normal value ranges from 8 to 16 mmol/L, calculated as sodium minus (chloride plus bicarbonate). Deviations from this range signal unmeasured or “hidden” anions—such as ketones, lactate, or urate—that standard panels often miss.

Recognizing this subtle shift transforms ambiguous results into actionable insights.

Standard laboratory methods for anion identification remain anchored in ion-selective electrodes and optimized際临实验室溶液滴定.

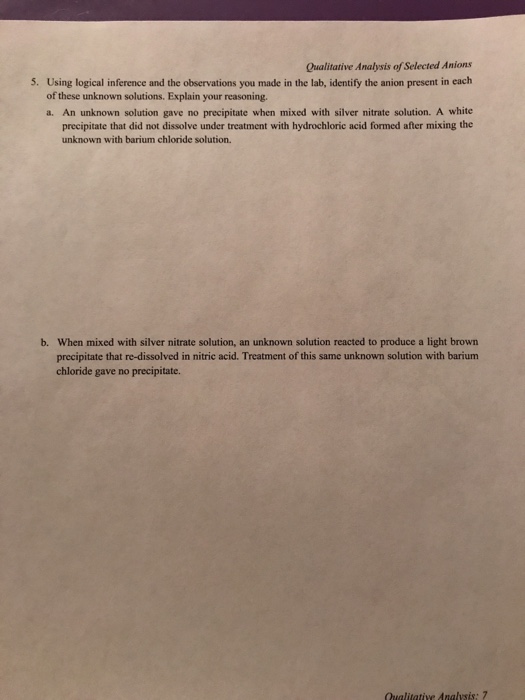

Culture and calibration are paramount. - Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) provide rapid, selective detection but require periodic charging and troubleshooting of interferences.- For accurate anion thràm, laboratory stewards emphasize proper titration techniques—using silver nitrate for sulfate, or precipitation methods with barium chloride for phosphate—ensuring moles are counted, not guessed. - Reference ranges vary by instrument, necessitating knowledge of manufacturer guidelines and sample matrix effects.

Consider common anions and their clinical fingerprints:

- Chloride (Cl⁻): Typically the most abundant in plasma (~96–106 mmol/L), chloride reflects renal balance and hydration status.

A drop below 95 mmol/L may hint at metabolic alkalosis or renal loss; a spike suggests dehydration or renal tubular acidosis.

- Bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻): Central to acid-base homeostasis, normal values hover between 22–28 mmol/L. Decline signals metabolic acidosis—seen in diabetes ketoacidosis or renal failure—while elevated levels indicate respiratory compensation or chronic alkalosis.

- Phosphate (PO₄³⁻): Lower levels (<2.5 mg/dL) may indicate refeeding syndrome or phosph terminated onset, especially in malnourished patients. Very high phosphate levels (>4.5 mg/dL) often accompany renal insufficiency or tumor lysis syndrome.

- Sulfate (SO₄²⁻): Normally 4.5–8.0 mg/dL, sulfate rises modestly in dehydration or renal tubular acidosis but is otherwise a passive metabolic byproduct.

- Carbonate (CO₃²⁻): Usually low (≤2.2 mmol/L), a sudden increase suggests acute metabolic alkalosis, often linked to vomiting or excessive diuretics.

Interpreting selected anions demands more than recall—it requires pattern recognition and clinical context.

For example, a patient with persistent metabolic acidosis and an elevated anion gap (>16 mmol/L) may have unmeasured angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, oxalate toxicity, or severe diabetic ketoacidosis. Yet, if chloride is ex constitutefected, chloride deficiency can mimic bicarbonate loss, a subtle pitfall well-documented in lab error analyses. Lab professionals routinely address these nuances using algorithms that weigh intact gas pressures, osmolal gaps, and extended electrolyte panels to isolate true anionic deviations.

Technological advances are

Related Post

Kansas Lottery: Mega Odds, Massive Cash Payouts, and Funding Public Dreams

Juan Joya Borja: Architect of Intellectual Rigor in Modern Thought

Stay in Good Standing: Mastering the School Absence Letter for Family Events

Uncover The Secret: Unraveling The Age Of The Rock’s Daughters