Define American Imperialism: Empires, Ambitions, and the Shaping of a Global Power

Define American Imperialism: Empires, Ambitions, and the Shaping of a Global Power

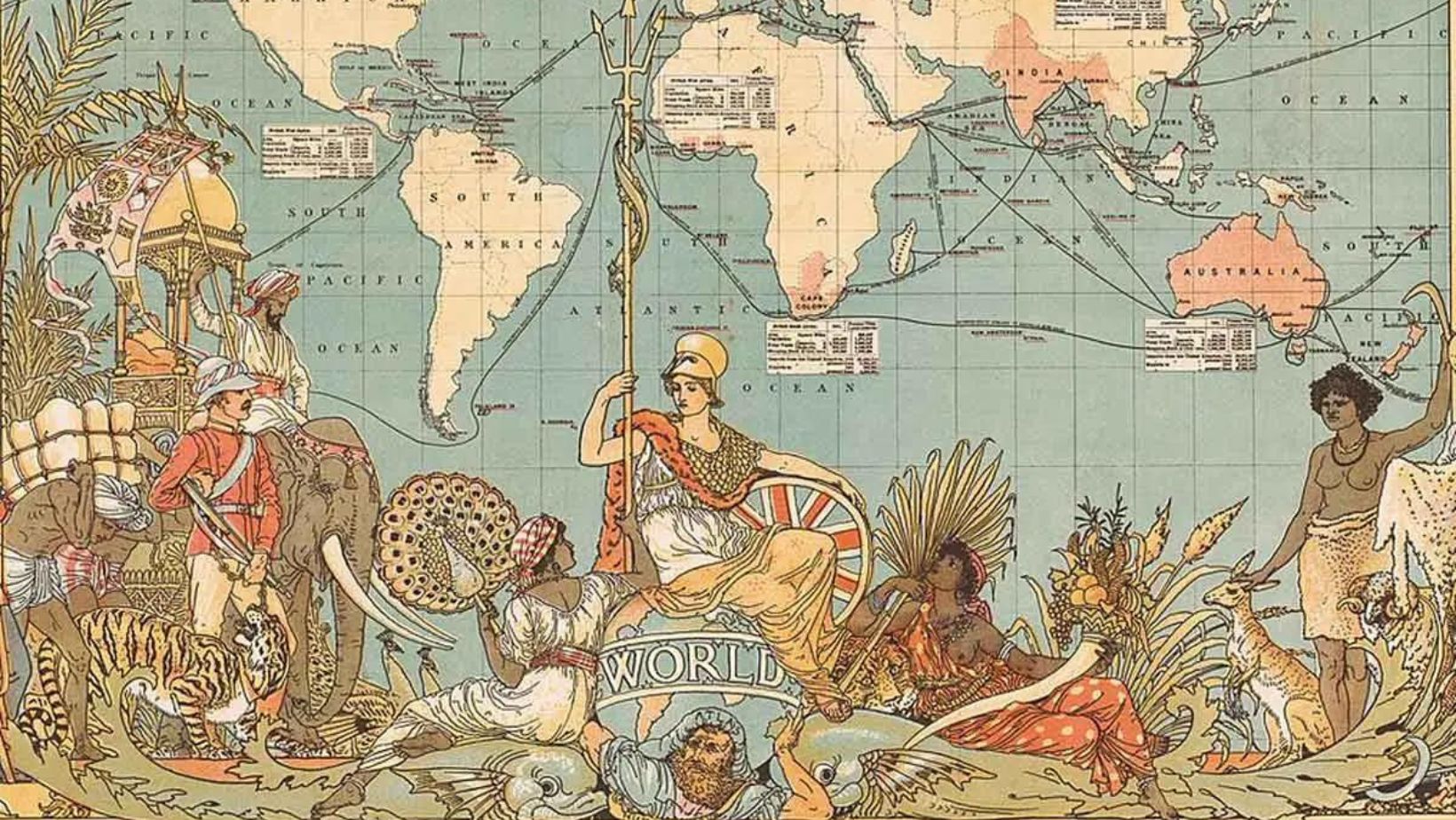

From territorial conquests that reshaped continents to economic and military influence that extended far beyond its shores, American Imperialism stands as a defining chapter in the nation’s history and global identity. Defined as the strategy through which the United States expanded its political control, economic dominance, and cultural reach from the late 19th century onward, this phenomenon reflects more than mere conquest—it embodies a complex interplay of ideology, strategy, and unintended consequence. American Imperialism emerged not as an abrupt shift but as a calculated evolution, driven by economic growth, military strength, and a belief in national destiny.

Understanding its trajectory reveals how the U.S. transformed from a continental republic into a global power with enduring influence across Pacific, Caribbean, and Atlantic regions. The roots of American Imperialism are deeply entwined with the aftermath of the Spanish-American War of 1898, a pivotal turning point that shattered the nation’s previous isolationist posture.

The defeat of Spain not only ended centuries of colonial control in the Caribbean and Pacific but also unleashed a wave of territorial acquisitions: Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines—each representing a commitment to overseas governance. As historian Thomas Sowell notes, “The United States found itself not merely as a military victor but as a colonial power, inheriting the responsibilities—and contradictions—of empire.” The annexation of the Philippines, in particular, ignited fierce domestic debate over whether empire aligned with American democratic ideals. American Imperialism manifested through multiple vectors: military force, economic integration, and cultural expansion.

The Philippines, for example, became the centerpiece of early imperial policy, where debates over Filipino self-determination exposed deep moral and political fractures. Beyond direct rule, the U.S. extended influence via unequal treaties, trade agreements, and financial investments that anchored Pacific economies to American interests.

Naval expansion—epitomized by the construction of a modern battleship fleet and the establishment of coaling stations—provided both strategic mobility and a visible symbol of imperial reach.

Military intervention remained a defining tool of American Imperialism. In Cuba, the Platt Amendment (1901) granted the U.S.

a formal right to intervene in Cuban affairs, effectively making the island a protectorate despite nominal independence. Similarly, in Hawaii, annexation in 1898 eliminated centuries of native governance and integrated a vital sugar-producing territory directly into the national economy. These actions, though often justified by claims of stability and modernization, systematically curtailed sovereignty and entrenched American control under legal and economic frameworks.

Economics shaped another pillar of imperial expansion. The United States leveraged its growing industrial capacity to dominate trade networks across the Pacific and Caribbean. U.S.

companies acquired vast plantations, mines, and utilities in territories, often displacing local entrepreneurs and redirecting wealth to American investors. In the Philippines, raw materials flowed eastward while American manufactured goods flooded local markets, creating patterns of dependency that endure in regional economic relations today. This economic imperialism, while spurring development in some sectors, simultaneously undermined indigenous economies and entrenched inequality.

Cultural dimensions of American Imperialism reveal a less-documented but equally powerful form of control. Missionary efforts, public education reforms, and media dissemination promoted English, democratic values, and American norms, embedding U.S. influence into the social fabric of conquered territories.

The Miles Brown High School in the Philippines and similar institutions played a critical role in shaping elite class structures aligned with American interests. These soft power tools, though subtle, helped naturalize U.S. presence and smoothed the path for prolonged administration.

Counter-movements emerged alongside imperial consolidation, most notably among Filipinos who resisted colonial rule through armed struggle and political activism. The Philippine-American War (1899–1902), marked by brutal combat and widespread civilian casualties, underscored the violent costs of empire. Domestically, anti-imperialist leagues—notably led by figures like Mark Twain and Filipino nationalist Emilio Aguinaldo—challenged the moral legitimacy of overseas expansion, arguing that empire contradicted foundational American principles of liberty and self-rule.

These debates laid early groundwork for modern discourses on interventionism and human rights.

By the mid-20th century, American Imperialism evolved with global dynamics. The shift from formal colonies to protectorates, aid-based relationships, and military alliances reflected a more nuanced strategy suited to Cold War geopolitics.

Bases in Guam and Puerto Rico remained critical to projecting power, while economic aid and trade partnerships extended influence without formal sovereignty. Today, the legacy persists in U.S. foreign policy, military presence, and cultural reach—evident in everything from diplomatic leverage to the global spread of American media.

Defining American Imperialism requires acknowledging its transformative ambition and its complicated, often contested outcomes. It was a strategy born of national pride and economic necessity, executed through a mix of force, diplomacy, and cultural assimilation. While it expanded American influence and reshaped global structures, it also generated enduring tensions over sovereignty, equity, and identity.

Understanding this history is essential—not merely to recount the past but to critically assess how imperial legacies continue to inform contemporary foreign relations, domestic values, and America’s role in an interconnected world.

In essence, American Imperialism is not a chapter neatly closed by

Related Post

Calm Sea, Beautiful Days: Episode 4 Epitomizes Serenity in Every Frame

Chris McKendry’s Net Worth: The Rising Force Behind a Multi-Million-Dollar Empire

WCA Production: The Engine Behind Modern Entertainment’s Most Beloved Experiences

BloxpartyOrg Pioneers Next-Gen Community Building in the Blockchain Gaming Space