Famous Romanticism Paintings: The Masterpieces That Defined an Era of Emotion and Vision

Famous Romanticism Paintings: The Masterpieces That Defined an Era of Emotion and Vision

Across the sweeping valleys, storm-tossed seas, and moon-drenched night skies of the Romantic era, art became a vessel for raw emotion, nature’s sublime power, and the inner turmoil of the human soul. Romanticism, flourishing from late 18th-century Europe to mid-19th century, transformed painting into an emotional earthquake—rejecting Cold Enlightenment rationality in favor of passion, drama, and spiritual transcendence. Nowhere is this more evident than in the iconic canvases that capture the spirit of Romanticism.

From churning monsoons to lone figures in eternal contemplation, these masterpieces transcend their frames to invite viewers into a world where feeling reigns supreme and beauty is inseparable from turmoil.

Using bold brushwork, dramatic lighting, and deeply symbolic narratives, these works redefined what art could express. As art historian Howard Holden observes, “Romantic painting is not a mere representation of landscapes and figures, but a visceral outcry of the soul confronting the infinite.”

Embracing the Sublime: Nature as Emotional Cathedral

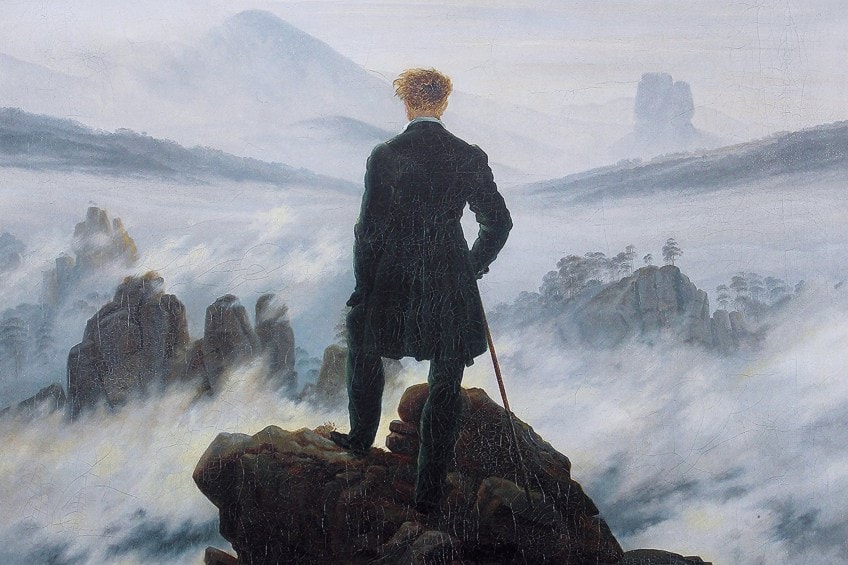

Romantic artists treated nature as a living, breathing entity—ever-changing, overwhelming, and spiritually charged. Instead of tame pastoral scenes, they painted cragging mountains, violent storms, and desolate wildernesses that mirrored inner human struggles.Among the most compelling examples is Caspar David Friedrich’s *Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog*, a 1818 oil on canvas that crystallizes Romantic ideals. A lone figure stands atop a rocky precipice, silhouetted against a swirling ocean of clouds and fog, gazing outward with quiet contemplation. Friedrich’s composition elevates nature as both a physical and metaphysical force—“the sublime is not merely seen,” he once wrote, “it is felt.” Friedrich’s use of perspective draws the viewer into the scene, implicating them in the emotional journey.

The vastness of the landscape underscores humanity’s smallness and vulnerability, yet the figure remains steadfast—particularly emblematic of Romantic individualism and resilience. Other luminaries, such as J.M.W. Turner, expanded this vision further into atmospheric chaos.

His *The Slave Ship* (1840), inspired by a real tragedy, renders a tempestuous sea not just as a natural phenomenon, but as a visual metaphor for moral horror and emotional devastation. “Nature,” Turner wrote, “gets her own voice in the tempest,” and his paintings often blur the line between observer and participant. - Friedrich’s *Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog*: A symbol of human introspection amidst overwhelming nature.

- Turner’s *The Slave Ship*: A searing fusion of nature’s fury and human suffering, rendered through turbulent brushwork. These works invite not passive viewing but emotional immersion—challenging audiences to confront their own place in an intense, unpredictable world.

Emotion Over Reason: The Stirring Drama of the Human Soul

While the Enlightenment championed reason and order, Romantic painters reveled in passion, grief, and existential yearning.Their canvases brim with psychological depth, portraying figures absorbed in grief, awe, or revolutionary fervor. Eugène Delacroix, the French Romantic titan, masterfully captured these emotions in *Liberty Leading the People* (1830), a monumental painting commemorating the July Revolution. The central figure of Liberty—a bare-breasted woman holding the tricolor flag—becomes both a military leader and a mythic symbol, rallying citizens through raw physical expression and symbolic grandeur.

Though historically inspired, the painting transcends documentation, becoming an eternal emblem of freedom’s emotional charge. Delacroix’s technique amplifies the drama: bold, sweeping brushstrokes, vivid contrasts of light and shadow, and a chaotic but orchestrated movement that propels the viewer’s eye across the scene. “Liberty does not speak in calculus,” he declared; “she speaks in fire, in blood, in hope.” This fusion of political urgency and personal anguish defines Romanticism’s core: beauty is never disconnected from feeling.

Other pivotal works deepen this exploration. In *The Death of Sardanapalus* (1827), Delacroix depicts theCDC of a king sacrificing his opulent court to avoid defeat—an explosion of color and anguish that portrays the tragic cost of hubris and emotional collapse. Similarly, Friedrich’s *Monk by the Sea* (1808–1810) features a solitary figure dwarfed by endless dark sky and barren shore, embodying existential solitude and the humility of man before the infinite.

Such images challenge viewers to confront solitude, mortality, and spiritual awakening all at once. - Delacroix’s *Liberty Leading the People*: A dynamic fusion of political revolution and emotional intensity. - *The Death of Sardanapalus*: A vivid, anguished dramatization of pride and downfall.

- Friedrich’s *Monk by the Sea*: A meditative study of isolation and cosmic vastness. These paintings reveal Romanticism’s insistence on art as a mirror of inner and collective soul-shattering realities.

Night, Mystery, and the Mystical: Into the Ethereal

The Romantic fascination extended beyond daylight to the twilight and night—domains where mystery, the supernatural, and the mystical flourished.Painters sought not just to depict stars and shadows, but to invoke a metaphysical dimension where the visible and invisible brushed against one another. William Blake’s visionary *The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun* (1805–10) exemplifies this, merging biblical apocalypse with personal symbolism. The vivid red dragon, clad in ominous fires, amidst swirling celestial force, embodies cosmic struggle and divine revelation.

Blake wrote that art “is the proprietor of the everlasting Beauty,” and his nightscapes deliver beauty charged with spiritual potency. John William Blake, though less widely known, similarly evokes mystery through subtler means. His *Night Landscape* (c.

1815) sediments a shadowed forest bathed in pale moonlight, where ghostly figures emerge from obscurity—each suggestion a whisper

Related Post

Maximizing Space: The Surprising Impact of 8cm in Every Design Choice

Tim NFL Terbaik Sepanjang Masa: Legenda & Warisan – The Immortal Impact of a Football Icon

The Final Twist of THE ETERNAL SEA: Unraveling *Pirates of the Caribbean III* Ending

Fl Oz To Ml: The Surprising Precision Behind Fluid Conversions in Science, Cooking, and Commerce