Heating & Cooling Curves: The Science Behind Phase Transitions Unveiled

Heating & Cooling Curves: The Science Behind Phase Transitions Unveiled

<وقع>Understanding phase transitions through heating and cooling curves reveals fundamental insights into the behavior of matter—from solid to liquid to gas and back—driven by the subtle interplay of energy and molecular motion. These temperature-dependent graphs capture more than just numerical shifts; they illustrate the invisible dance of atoms as they absorb or release heat, undergoing dramatic transformations that define materials’ physical properties. From diagram walls to industrial applications, heating and cooling curves serve as essential tools in science, engineering, and education.

At the heart of every heating and cooling curve lies the concept of phase equilibrium—states where two phases coexist in balance at a given temperature and pressure.

As energy input increases, molecular activity surges: vibrational motion intensifies, bonds loosened, leading to melting, vaporization, or sublimation. Each transition marks a distinct plateau or jump on the curve, grounded in precise thermodynamic principles. “The curve isn’t just data—it’s a timeline of molecular intent,” notes Dr.

Elena Torres, a physical chemist specializing in materials science.

Decoding the Key Features of Heating & Cooling Curves

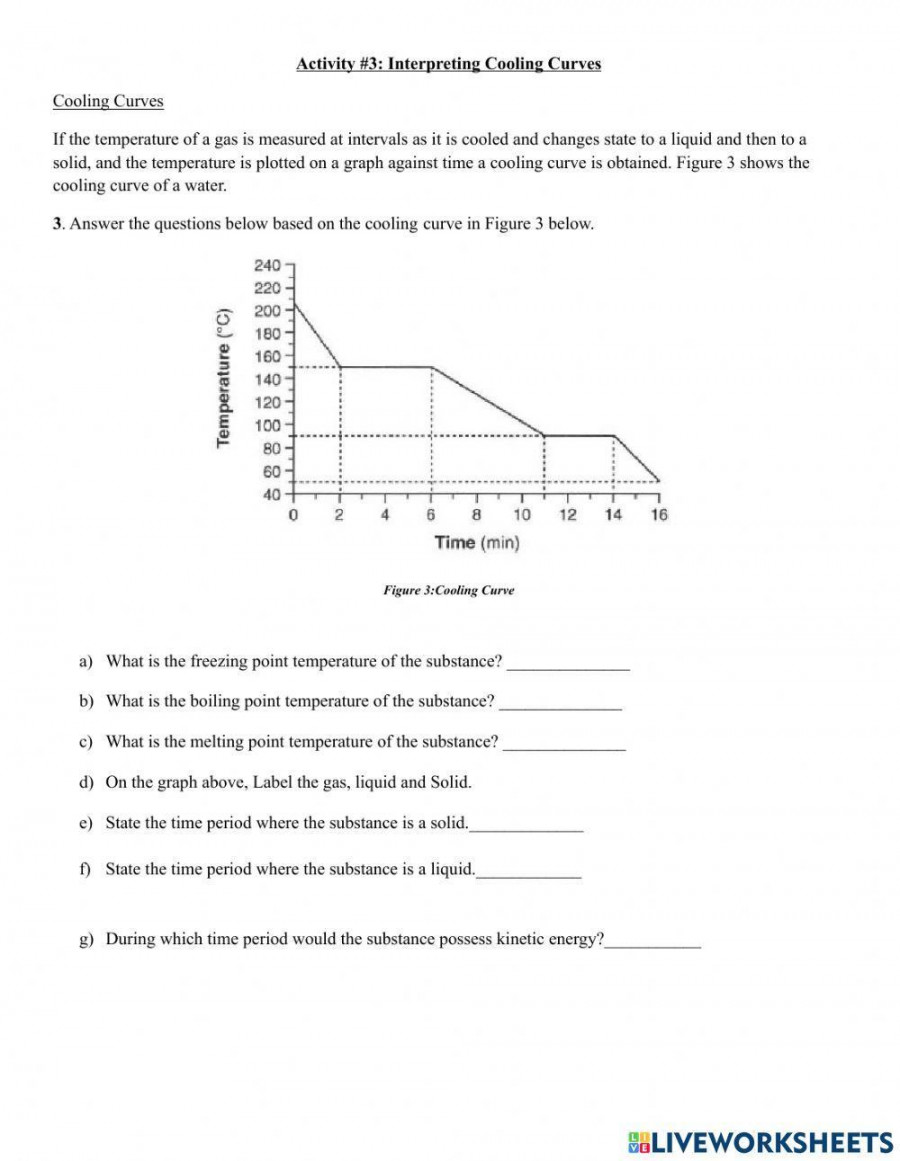

Heating and cooling curves share a common visual framework but reflect opposite thermal journeys. On a typical heating curve, the graph climbs with defined stages:

- Melting (Solid → Liquid): A near-vertical rise signals latent heat absorption as crystalline structure breaks down.

- Vaporization (Liquid → Gas): A pronounced plateau at the boiling point reveals significant energy input with no temperature change—evaporation powered by intermolecular bond rupture.

- Sublimation (Solid → Gas): Rare in common substances but critical in freeze-drying and dry ice applications.

Each curve harbors telling details:

- Slope Steepness: Determines rate of temperature change; flatter slopes during phase transitions reflect high latent heat, while steeper gradients signal sensible heating or cooling.

- Phase Boundaries: Sharp lines define phase transition temperatures under equilibrium conditions; deviations arise under non-equilibrium scenarios like rapid cooling or supercooling.

- Triple and Critical Points: Unique intersections—such as the triple point where all three phases coexist—anchor theoretical models, while critical points mark the limits beyond which liquid and gas dissolve into a supercritical fluid.

Phase Transitions: From Water to Crystals

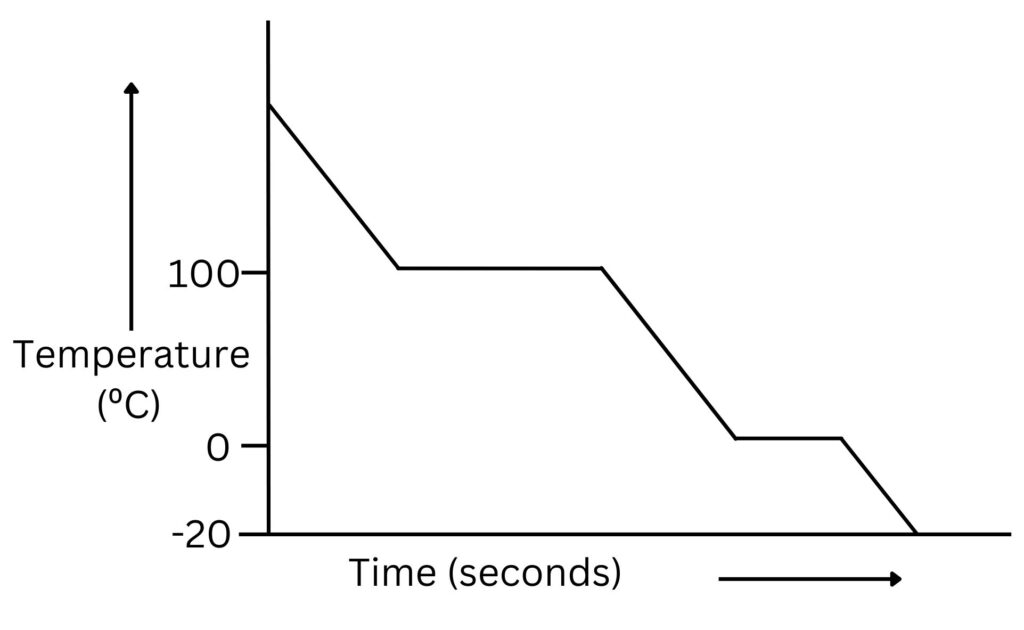

No diagram captures phase dynamics more clearly than water’s heating and cooling curve.

At 0°C under standard pressure, the curve steepens sharply as ice absorbs latent heat to become liquid—a plateau lasting minutes, each degree absorbed quietly. “This isn’t just melting—it’s a battle between order and chaos,” explains Dr. Torres.

“Water resists becoming liquid, holding tight to its ordered lattice, until energy overcomes hydrogen bonds.”

At 100°C, vaporization begins, with energy fully invested in breaking molecular bonds rather than raising temperature. Then vapor cools, condensing with energy release—visible as a horizontal drop on the cooling curve. The latent heat values define material identity: high latent heat in paraffin enables efficient thermal storage, valuable in temperature regulation systems.

In metals and alloys, heating curves reveal solidification temperatures where crystals regenerate, guided by the same thermodynamic rules.

These transitions are vital in metallurgy: controlled cooling prevents defects, ensuring structural integrity in steel, aluminum, and precision components.

Practical Applications Across Science and Industry

Understanding heating and cooling curves extends far beyond academic curiosity—they drive innovation. In food science, freeze-drying leverages sublimation curves to preserve perishables without ice damage, maintaining texture and flavor. In pharmaceuticals, lyophilization relies on precise cooling to remove water while protecting molecular structure.

In climate science, phase transitions of water—evaporation, condensation, freezing—regulate atmospheric energy transfer.

“Every cloud’s formation and rain’s descent are encoded in those curves,” says a climatologist. The latent heat released during condensation powers storms, making phase behavior central to weather modeling.

Industrial processes depend equally on these principles. In polymer manufacturing, controlled heating prevents premature degradation, while annealing relies on cooling curves to relieve internal stresses, enhancing material durability.

Thermal energy storage systems use phase change materials (PCMs) whose latent heat during melting and solidification provide efficient, sinkable energy buffers for solar grids and smart buildings.

The Unseen Forces Shaping What We Touch

Heating and cooling curves distill complex thermodynamics into直观 visual progressions—graphs where every plateau and spike tells a story of molecules contracting, expanding, and transforming. Far from static, these curves embody equilibrium, energy transfer, and the unseen driving forces beneath phase transitions. From freeze-dried spices to steel beams, from raindrops to refrigerants, they offer a window into matter’s adaptive behavior under thermal influence.

Mastery of these curves empowers not just scientists, but engineers, analysts, and educators—giving them the clarity to predict, manipulate, and apply phase transitions with precision. Understanding heating and cooling curves is not merely studying heat

Related Post

Julie Chrisley: Is She Lindsies Mom? Unraveling a Public Identity

Chris Stapleton Trump: The Unexpected Crossroads of Country Pop and Political Fire

How Apple’s Pineapple Pen Lyrics Spark a Surprising Revolution in Digital Expression

Marion Il Your Guide To The Illinois Crossroads