Inertia Of A Cylinder

The Hauling Power Behind Motion: Understanding Inertia in Rotating Cylinders When a cylinder spins, the invisible force resisting its acceleration—its inertia—shapes how machinery behaves, from industrial engines to everyday tools. Inertia of a cylinder, rooted in Newtonian mechanics, reveals how mass distribution and rotational dynamics dictate performance, efficiency, and stability. This phenomenon, often overlooked, is fundamental to engineering design, reliability, and control systems.

Understanding the inertia of a cylinder under real-world loads enables smarter innovation across mechanical, automotive, and aerospace applications.

What Determines the Inertia of a Rotating Cylinder?

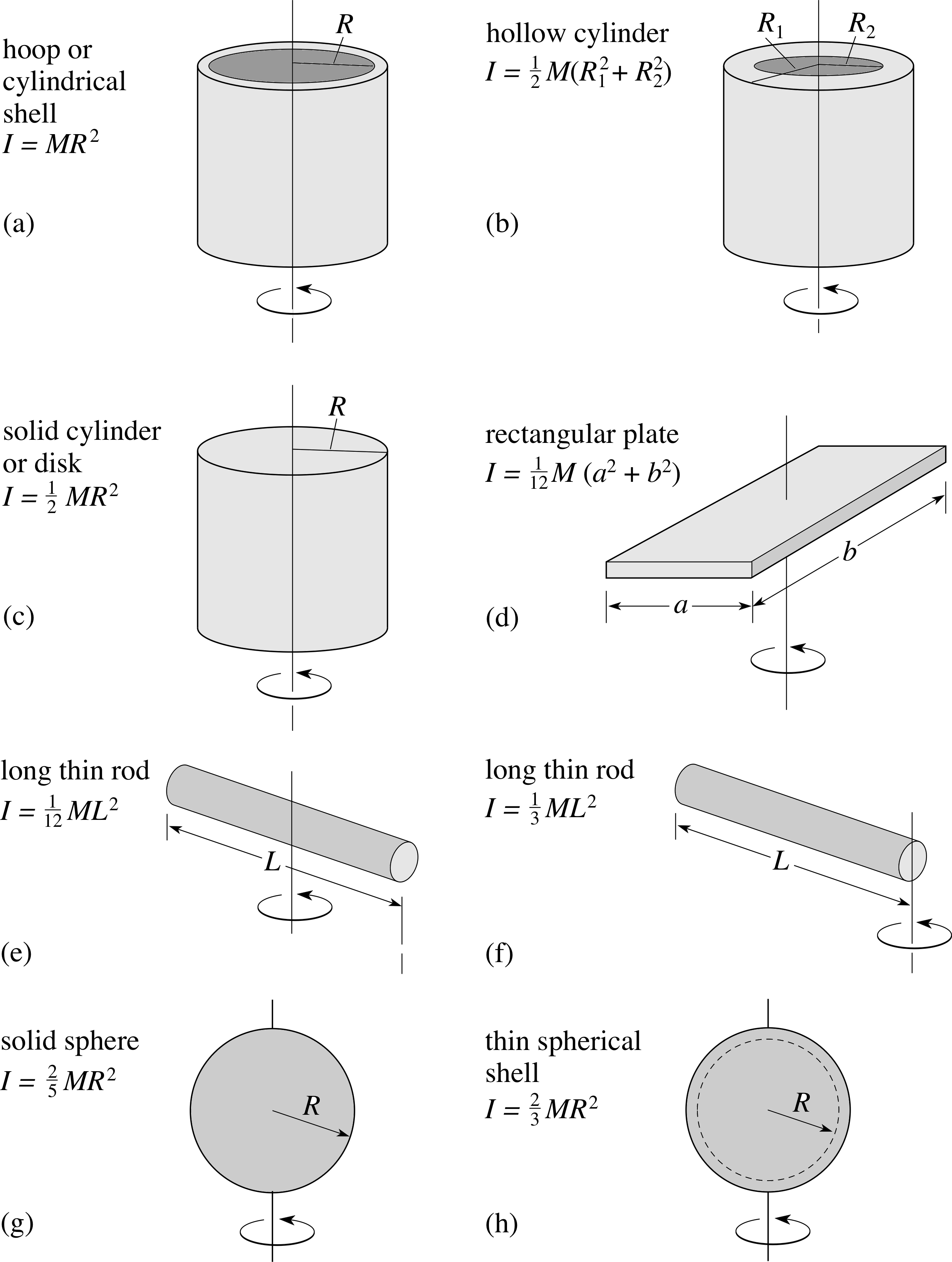

Inertia, defined as an object’s resistance to changes in motion, applies directly to rotating cylinders as rotational inertia or moment of inertia. This resistance depends on two primary factors: mass distribution and rotational speed.For a solid cylindrical rotor, mass concentrated farther from the axis increases inertia significantly—so much so that doubling the radius can quadruple rotational inertia, purely by altering how mass is spatially arranged. The core formula governing rotational inertia is L = I·ω, where I is the moment of inertia, ω the angular velocity, and L the angular momentum. “The further mass extends from the axis, the greater the resistance to angular acceleration,” explains Dr.

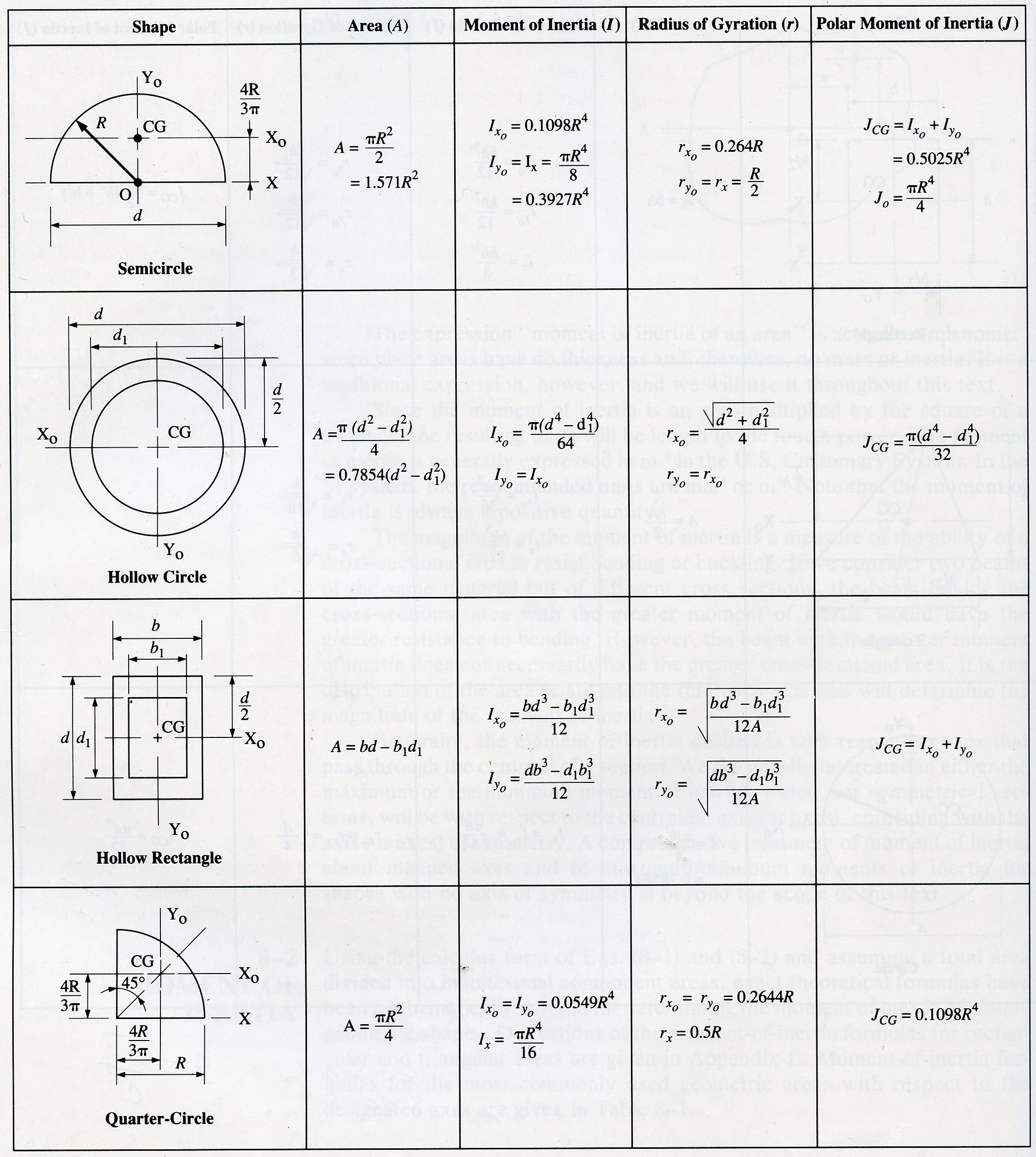

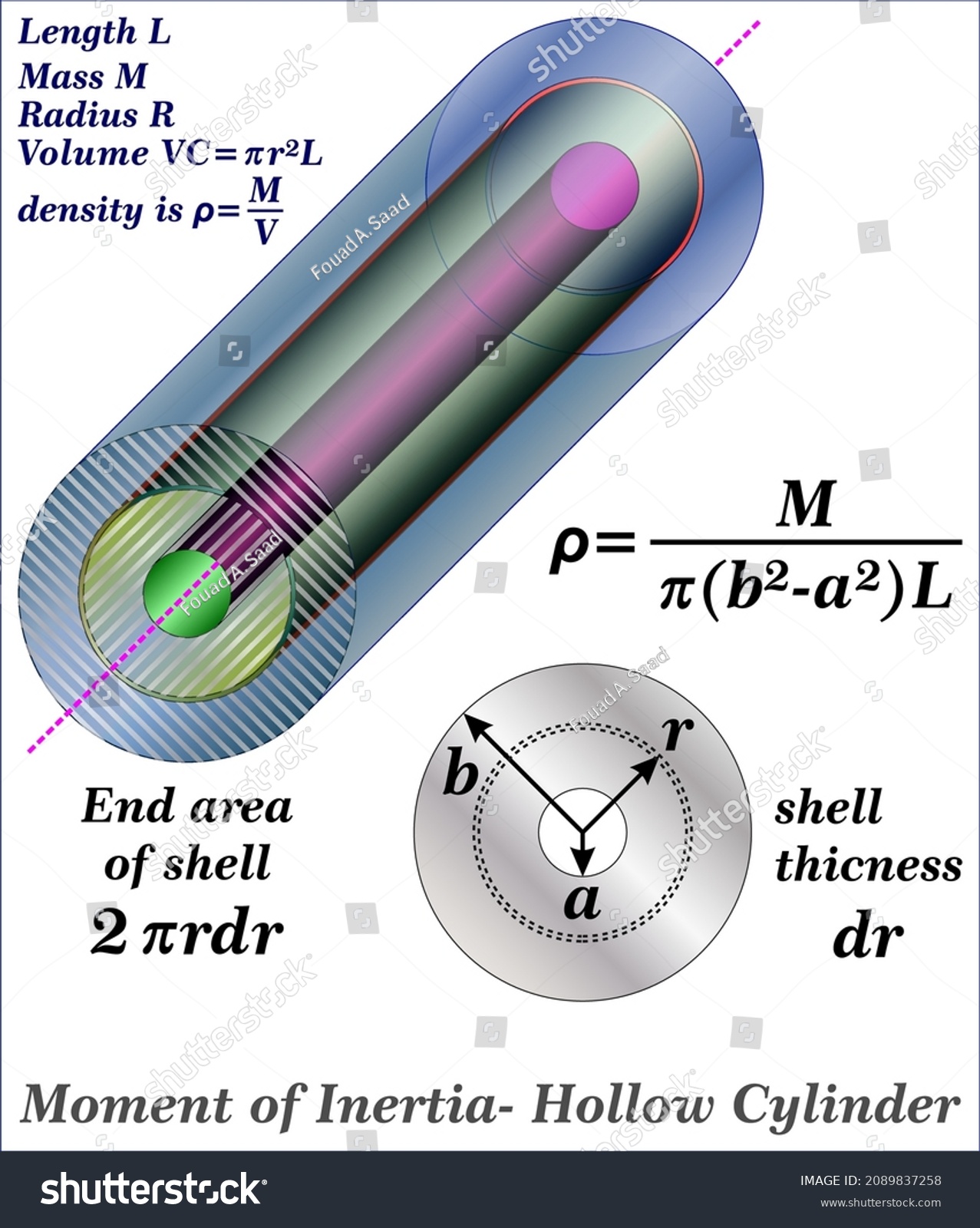

Elena Torres, a senior mechanical engineer at the Institute for Mechanical Dynamics. “This means a cylinder’s shape—its diameter, wall thickness, and density gradient—directly influences how force translates into rotational motion.” Physicists express rotational inertia mathematically using integrals over mass elements: I = ∫ r² dm for a continuous mass distribution, where r is the distance from rotation axis, and dm represents infinitesimal mass segments. For common solid cylinders—used widely in motors, flywheels, and pumps—simplified models like I = (1/2)mr² apply when mass is symmetrically distributed.

However, irregular geometries or hollow designs demand precise computation through CAD simulations and experimental validation.

Real-World Implications: Why Inertia Like This Matters Beyond Theory

In high-torque environments such as drilling platforms or industrial mixers, the inertia of a cylinder dictates energy requirements, motor sizing, and startup torque. A heavy, slowly rotating cylinder resists acceleration, demanding stronger motors and control strategies to overcome inertia-induced delays.Conversely, lightweight, high-speed cylinders—like flywheel energy storage units—leverage optimized inertia to store and release kinetic energy rapidly, crucial for grid stabilization and regenerative braking in electric vehicles. Hollow cylinders present unique behavior: while they reduce overall mass, their inertia becomes sensitive to wall thickness and internal structure. “In hollow shafts, doubling wall thickness doesn’t linearly increase inertia—it amplifies rotational inertia more than proportionally, due to r⁴ dependence in thick-walled formulations,” notes Dr.

Torres. Engineers must therefore balance structural integrity with inertial performance, often using lightweight composites or variable-density materials. Case Studies: From Motors to Machinery Three applied domains vividly illustrate the impact of cylinder inertia:

- Electric Vehicle Drivetrains: Cylindrical motors in EV axles feature carefully balanced mass profiles.

High inertia motors deliver smooth, powerful starts but require precision control to avoid lag. Manufacturers optimize rotor weight distribution to minimize lag while maximizing energy efficiency—turning inertia from a constraint into a design advantage.

- Construction Equipment: Cylindrical hydraulic cylinders in bulldozers or excavators endure cyclic loading and variable speeds. Inertia affects responsiveness: overly heavy sleeves slow actuation, while low inertia increases vibration.

Modern designs use counterweights and composite sleeves to tune inertia, enabling rapid, stable operation under variable stress.

- Aerospace Systems: Rotating machinery in spacecraft—such as gyroscopes and reaction wheels—relies on ultra-low inertia. Every gram saved and every millisecond of response time is critical. Carbon-fiber-laminated cylinders reduce inertia by up to 40% compared to traditional metal rods, enhancing agility and precision in microgravity environments.

Fixed-speed systems disregard inertia’s transient effects, but modern variable-frequency drives and adaptive controls actively compensate for it, ensuring smooth transitions and reduced wear. Feedback sensors monitor angular velocity and torque, adjusting motor input in real time to counteract inertia-induced overshoot and instability.

Engineering the Balance: Overcoming Inertia Challenges

Designing systems around cylinder inertia requires a multi-disciplinary approach.Computational modeling using finite element analysis (FEA) simulates stress and inertia across operating conditions, predicting failure points and optimizing wall thickness or internal ribbing. Experimental validation using laser doppler vibrometers and inertial sensors verifies model accuracy and ensures alignment with real-world performance. Material selection compounds the challenge.

Aluminum alloys offer favorable strength-to-mass ratios but may underperform compared to advanced composites, which combine low density with high stiffness. “Hybrid constructions—metal cores with carbon-fiber sleeves—represent the cutting edge,” says Dr. Torres.

“They deliver strength where needed while dramatically lowering rotational inertia, enabling faster, cleaner operation.” Thermal effects further complicate matters. Rotational friction generates heat, altering material properties and expanding components, which subtly shifts mass distribution. Engineers incorporate thermal expansion coefficients into design margins and utilize active cooling in high-performance systems to mitigate inertia variability.

The Future of Rotational Inertia in Cylindrical Systems

As industries move toward lighter, faster, and smarter machinery, understanding and engineering rotational inertia will remain pivotal. Emerging technologies—such as additive manufacturing—allow unprecedented control over internal geometries, enabling tailored moment-of-inertia profiles impossible with traditional casting or machining. Smart materials with variable stiffness or shape-memory alloys may offer real-time inertia modulation, adapting to changing loads on the fly.From electric vehicles demanding responsive drivetrains to aerospace systems requiring razor-sharp maneuverability, the inertia of a cylinder governs efficiency, precision, and reliability. Advances in simulation, material science, and adaptive control are transforming how engineers harness—or constrain—this fundamental physical property. By mastering inertia, the industry unlocks new frontiers in motion, energy, and control.

Inertia of a cylinder is not a mere theoretical footnote—it is the silent architect shaping how machines turn power into progress, one revolution at a time.

Related Post

Unveiling The Love Life Of Bianca Bustamante: Who Is Her Boyfriend?

Empowering Student Success: Unveiling Lamar University’s Innovative Self-Service Portal

DHL Paket Versand: Your Definitive Guide to Sending Packages Across Germany

Emily Threlkeld Unlocks the Secrets of Language Intelligence with Groundbreaking Research