Is Fructose a Monosaccharide? The Sweet Sugar Redefined

Is Fructose a Monosaccharide? The Sweet Sugar Redefined

Fructose, long revered as nature’s sweetest ally, is not merely a flavorful enhancer but a biochemical powerhouse—specifically, a monosaccharide with unique metabolic pathways and physiological roles. Far more than just "fruit sugar," fructose operates at the intersection of nutrition, biochemistry, and health, making its classification as a monosaccharide central to understanding modern dietary science. Unlike sucrose or glucose, fructose stands apart in structure, metabolism, and impact, demanding clearer insight into whether—and how—it qualifies as the quintessential monosaccharide.

Defining the Monosaccharide: Structure and Fundamentals

At its core, a monosaccharide is a single, non-digestible unit of sugar—small enough to be absorbed directly into the bloodstream without breakdown in most cases.

Found in the simplest forms of carbohydrates, monosaccharides serve as the building blocks for more complex sugars like disaccharides and polysaccharides. The term “mono” reflects their singular molecular structure, distinguishing them from oligosaccharides (two to ten units) and polysaccharides (chains of hundreds or more). Among the primary monosaccharides—glucose, fructose, and galactose—fructose is distinguished by its molecular configuration and metabolic behavior.

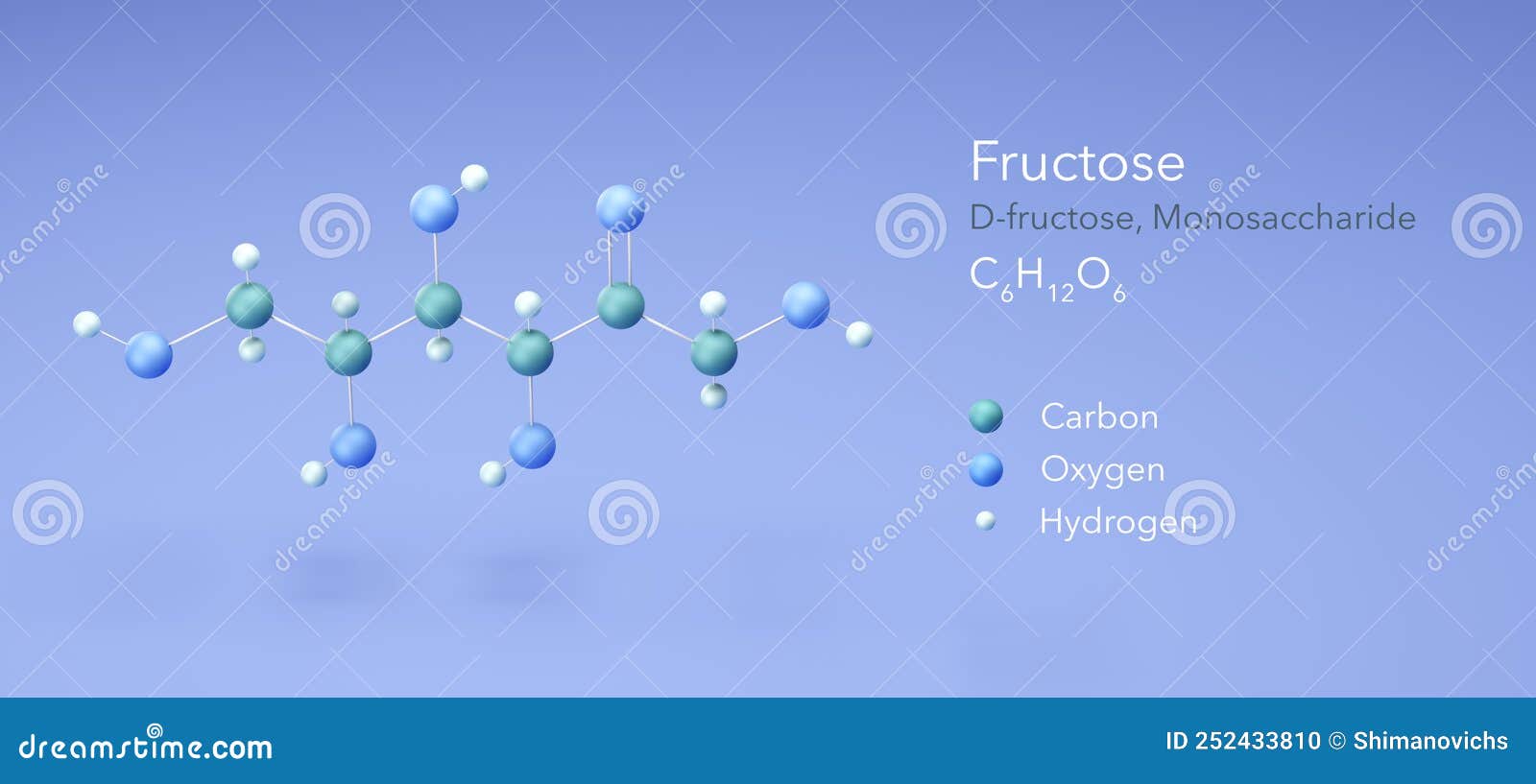

Chemically, fructose is structurally defined by a ketone functional group and a molecular formula of C6H12O6, placing it firmly within the aldose class of hexoses.

Its precise backbone—with hydroxyl groups positioned in a manner that gives it a pronounced sweetness—explains its intense flavor profile. “Fructose’s structure is not just molecularly elegant—it’s biologically strategic,” observes Dr. Elena Torres, carbohydrate biochemist at the Institute of Nutritional Sciences.

“The position of its double bonds and hydroxyl orientation directly influence how enzymes recognize and process it.”

Fructose: A Monosaccharide Among Unique Metabolic Pathways

While glucose and galactose rely on insulin-dependent uptake via transporters like GLUT4, fructose takes a distinct route. Metabolized primarily in the liver, fructose enters cells through the GLUT5 transporter, bypassing major regulatory checkpoints. This allows rapid assimilation but shifts its processing away from typical energy pathways.

“Fructose doesn’t trigger insulin release the same way,” explains Dr. Torres, “meaning its metabolism is free from the feedback loops governing glucose. This makes its fate uniquely tied to hepatic function—whether beneficial or burdensome depending on intake levels.”

Key to understanding fructose’s classification is its metabolic fate.

Unlike glucose, which fuels nearly every cell, fructose is largely processed in the liver, where it fuels de novo lipogenesis—the creation of fat from carbohydrate. This pathway, while natural in moderation, becomes problematic when consumed in excess, linking high fructose intake to metabolic disorders such as insulin resistance and fatty liver disease. “It’s not that fructose is inherently bad,” says Dr.

Torres, “but its singular hepatic exploitation demands careful balance in dietary patterns.”

Fructose in Nature: From Fruit to Function

In natural sources like apples, grapes, and honey, fructose rarely exists in isolation. It coexists with glucose, fiber, and phytochemicals—components that modulate its absorption and metabolic consequences. This synergy shapes how the body handles fructose compared to isolated forms found in sweetened beverages and processed snacks.

“Whole fruits deliver fructose alongside natural fiber and antioxidants,” notes nutritional epidemiologist Dr. Rajiv Mehta. “These co-factors blunt the rapid blood sugar spikes that occur with liquid sugars, illustrating intake context matters profoundly.”

The distinction between natural and added fructose remains pivotal.

Natural fructose from whole foods is metabolized safely alongside protective nutrients, whereas concentrated added fructose—common in sodas and ultra-processed snacks—lacks these mitigating elements, increasing health risks. “The matrix of food matters,” Mehta stresses. “Fructose from an apple and fructose from high-fructose corn syrup reflect two vastly different physiological realities.”

Debunking Myths: Fructose as Monosaccharide vs.

Is It ‘Bad’

Despite concerns linking fructose to obesity and metabolic syndrome, science clarifies its role not as inherently toxic, but context-dependent. “Fructose is a monosaccharide—and like all sugars, its impact depends on quantity, source, and overall diet,” explains Dr. Maria Chen, a clinical nutrition specialist.

“Moderation within a balanced diet poses minimal risk; excess intake, particularly of ultra-processed sources, correlates with adverse outcomes.”

What does current research say? The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition highlights that fructose metabolism, when paired with fiber and micronutrients, does not inherently drive chronic disease. Conversely, isolated fructose in sugary drinks, consumed without counterbalancing nutrients, raises insulin resistance markers and visceral fat accumulation.

“The body evolved to process fructose in moderation, not in concentrated bursts,” Chen adds. The monosaccharide is not the enemy—overconsumption and misuse are.

The Bottom Line: Fructose as a Defined Monosaccharide with Nuanced Implications

Fructose unequivocally qualifies as a monosaccharide, sharing core identity with glucose and

Related Post

Dryer Element Replacement: The Key to Restoring Performance and Lifespan in Your Home Dryer

I Am Woman: The Empowering Lyric Journey Through Helen Reddy’s Iconic Anthem

How to Draw Pokémon: Master the Art with Precision and Passion

From Oldest to Youngest: How the Backstreet Boys Evolved Across Generations