Is Sublimation Endothermic or Exothermic? Unlocking the Thermal Secret of Solid-to-Gas Transitions

Is Sublimation Endothermic or Exothermic? Unlocking the Thermal Secret of Solid-to-Gas Transitions

Sublimation—the mysterious shift from solid to gas without passing through liquid—brings more than just scientific curiosity; it reveals crucial insights into energy dynamics in materials. Central to this phase change is the question: is sublimation endothermic or exothermic? The answer lies firmly in the realm of energy absorption, fundamentally defining how substances behave under specific temperature and pressure conditions.

Understanding this distinction not only clarifies thermodynamic principles but also drives innovation in industries ranging from freeze-drying technology to atmospheric science.

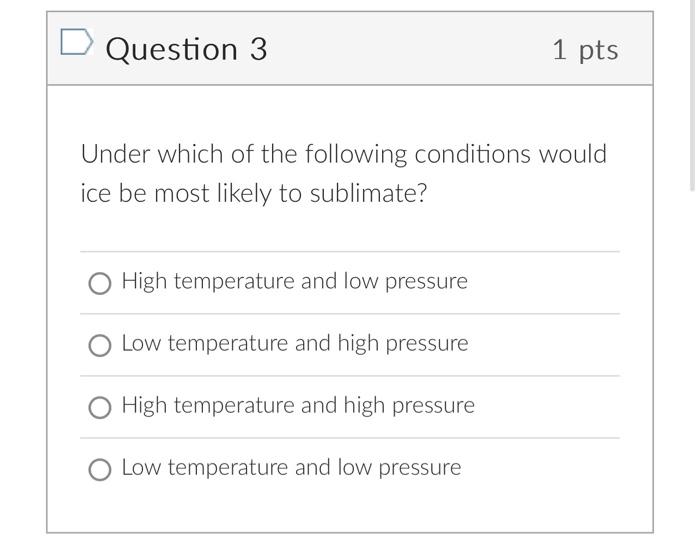

The Thermodynamic Classification of Sublimation

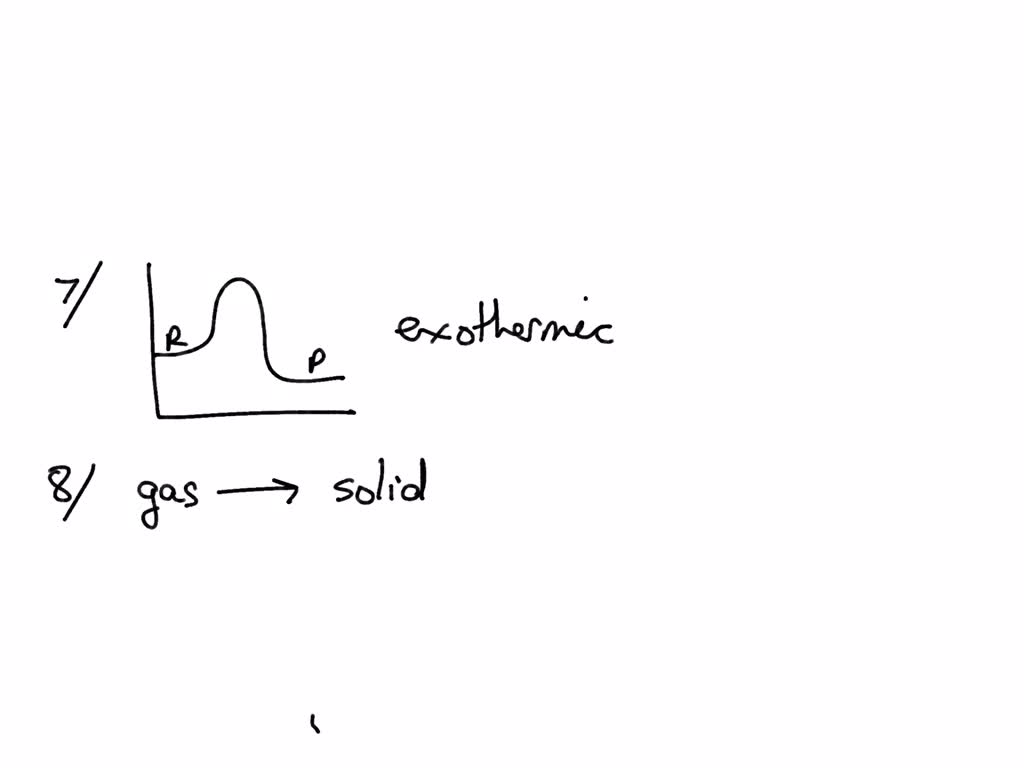

Sublimation is universally classified as an endothermic process. To grasp this requires delving into the core principles of thermodynamics: endothermic reactions absorb heat from their surroundings, while exothermic reactions release it. During sublimation, a solid directly transitions to vapor, bypassing the liquid phase entirely—a process driven exclusively by energy input.

The external energy overcomes intermolecular forces holding the solid structure together, enabling molecules to escape into the gas phase with higher kinetic energy. This energy requirement is the hallmark of an endothermic transformation.

Scientists quantify sublimation’s endothermic nature through enthalpy values. The sublimation enthalpy (ΔHsub) represents the precise amount of heat required per mole to drive this phase change at a given temperature and pressure.

For most common substances—such as dry ice (solid carbon dioxide) or iodine—the sublimation enthalpy ranges from approximately 25 to 52 kJ/mol, reflecting strong but not impossibly extreme energy demands. “When dry ice sublimates in room temperature air, it draws heat from its environment, cooling the surrounding surface by several degrees Celsius,” explains Dr. Elena Marquez, a physical chemist specializing in phase transitions.

“This visible cooling effect confirms the endothermic process in action.”

Why Sublimation Absorbs Energy: Molecular Perspectives

At the molecular level, sublimation requires breaking solid lattice bonds without liquid intermediates. In a solid, molecules vibrate within a fixed arrangement, held firmly by intermolecular forces. To enter the gas phase, molecules must first gain enough kinetic energy to escape these attractions—a process that demands substantial energy input.

This energy uptake destabilizes the solid structure, enabling molecules to break free and disperse as gas. Any release of energy during this process would imply exothermic behavior, which contradicts the fundamental physics of sublimation. “Once the solid lattice is overcome, no subsequent energy is released; instead, energy flows inward from the surroundings,” notes Dr.

Raj Patel, a materials scientist at the Institute of Crystalline Sciences. “This unidirectional flow confirms sublimation’s endothermic character.”

Environmental conditions heavily influence whether a substance sublimates and how energy is exchanged. At pressures below the triple point—such as at high altitudes where atmospheric pressure is low—sublimation becomes thermodynamically favorable even at standard room temperature.

For example, snow remains frozen when exposed to cold desert air because sublimation removes moisture directly into vapor without melting. In controlled settings like vacuum freeze-drying, sublimation is deliberately harnessed: reducing pressure allows ice to sublimate at subzero temperatures, preserving delicate structures in pharmaceuticals without heat damage. “The endothermic requirement means sublimation cools the immediate environment,” adds Dr.

Marquez. “This property is critical in cryopreservation and space-based material storage, where thermal management is paramount.”

Practical Applications Fueled by Endothermic Sublimation

Sublimation’s endothermic nature powers numerous real-world technologies. The most familiar example is freeze-drying, or lyophilization.

By forming ice in biological samples or foodstuffs and then lowering pressure, sublimation removes water without damaging cellular structures or altering flavor. This process, widely adopted by the medical and food industries, extends shelf life while preserving nutrient integrity—all made possible by harnessing the endothermic heat absorption. “Freeze-drying doesn’t freeze water; it converts it directly to vapor via sublimation, cooling the material internally while safeguarding its molecular architecture,” says Dr.

Patel. “Without understanding its endothermic foundation, modern biopharmaceutical preservation would be unfeasible.”

Beyond freeze-drying, sublimation plays roles in atmospheric science and geology. In polar regions, dry ice sublimates into the thin atmosphere, influencing local microclimates.

On Mars, seasonal carbon dioxide ice caps sublimate during spring, releasing gas that shapes wind patterns and surface features. These natural occurrences underscore the global significance of sublimation as an energy exchange process, driven by endothermic principles that distribute heat across planetary systems. “Planetary heat budgets depend on phase transitions like sublimation,” explains Dr.

Marquez. “Understanding whether they absorb or release energy helps model climate systems more accurately across diverse environments.”

Comparatively, suppression of sublimation requires energy input—especially in industrial dehydration and moisture control—because reversing the process demands reheating to surpass already absorbed sublimation enthalpies. Conversely, exothermic cooling methods, such as evaporative cooling, expel heat through phase change but move in the opposite thermodynamic direction, releasing rather than absorbing energy.

The clear delineation between these processes enables engineers and researchers to design precision thermal systems, optimizing efficiency across sectors from aerospace to food preservation. “The predictability of sublimation as endothermic enables reliable engineering solutions,” notes Dr. Patel.

“Engineers rely on this science to build devices that manipulate phase changes with precision.”

The Broader Scientific and Everyday Impact

Sublimation’s role transcends industrial applications, embedding itself in everyday intuition. When one observes frost disappearing on a windowpane on a cold morning—despite nearly freezing temperatures—the process is sublimation in action, drawing heat from glass and air to transform ice directly into vapor. This subtle interaction quietly demonstrates endothermic energy uptake, a phenomenon often overlooked until examined closely.

In scientific education, this tangible example transforms abstract thermodynamic concepts into observable reality, reinforcing learning through real-world demonstration. “Teaching sublimation through visible, ambient examples bridges theory and practice,” asserts Dr. Marquez.

“It illustrates not just endothermic behavior, but how energy shapes our material world in quiet, powerful ways.”

Related Post

Oklahoma’s Zip Code Landscape: Decoding How Locality Shapes Daily Life and Opportunity

Timeless Love Crosses Borders: South Indian Romance Dubbed for China’s Audience

Rob Hall: The Enduring Legacy of a Mountain Legend Who Defined Alpine Courage

Is Kaitlyn Collins Married? Unveiling the Personal Life of the Rising Hollywood Star