Master Chem Lab Survival: How Limiting Reagents Transform Precision in Practice Problems

Master Chem Lab Survival: How Limiting Reagents Transform Precision in Practice Problems

Chemistry lab students face more than just complex reactions—they battle constraints rooted in measured quantities. In practice limiting reagent problems, mastery lies not just in stochiometry, but in the strategic application of reagent control. These exercises sharpen decision-making, demand precision, and mirror real-world lab limitations.

Solving them requires isolating the reagent that definitively ends a reaction—often the pivot point between safety, cost, and efficiency.

To succeed in practice limiting reagent problems, chemists must first understand the fundamental principle: a limiting reagent is the substance that is completely consumed first, thereby defining the maximum product yield. Unlike excess reagents, which remain after reaction completion, limiting reagents cap reaction scope.

In academic settings, students encounter a variety of questions demanding exact calculations—often under time pressure and with incomplete data. The ability to navigate these challenges separates proficient learners from novices.

Decoding the Core Challenge: Identifying the Limiting Reagent

At the heart of limiting reagent problems is a single question: which reagent runs out first? This determination hinges on comparing molar ratios of reactants relative to balanced chemical equations.Consider the reaction: 2Al + 3Cl₂ → 2AlCl₃ Here, 2 moles of aluminum react with 3 moles of chlorine gas. If a student is given only 4 moles of Al and 6 moles of Cl₂, both reagents appear equal in quantity—but the ratio matches exactly the stoichiometric requirement (2:3), meaning neither runs out first. But suppose only 5 moles of Cl₂ are available.

Using the ratio: 5 mol Cl₂ × (2 mol Al / 3 mol Cl₂) ≈ 3.33 mol Al needed; Available: 4 mol Al — still sufficient. But Cl₂ is limiting only when 5 mol Cl₂ supports ≤ 5 mol Al in reaction equivalence. The key insight: compare actual amounts against stoichiometric ratios.

Many students err by assuming equal moles imply equal availability, missing the nuanced balance required. A classic trap arises when data is incomplete—missing volumes, concentrations, or molar masses. In practice, precise unit conversions and clear balancing are non-negotiable.

Dexterity with stoichiometry ensures consistency across problems, from simple mole ratios to complex labs involving solution concentrations and volume-dependent reagent usage.

Step-by-Step Mastery: Solving a Limiting Reagent Problem

Consider this realistic scenario: A synthesis requires 150 mL of 0.2 M HNO₃ and 0.15 M NaOH to form H₂O and NaNO₃. Only 80 g of NaOH (molar mass 40 g/mol) is available. Determine the limiting reagent and theoretical yield.- Step 1: Calculate moles of available NaOH Moles NaOH = mass / molar mass = 80 g / 40 g/mol = 2.0 mol.

- Step 2: Convert volume to concentration Volume = 150 mL = 0.150 L. Concentration = moles / volume = 2.0 mol / 0.150 L = 13.3 M — unusually high, but assume correct for pedagogical model.

- Step 3: Assume HNO₃ is in excess—solve for NaOH limit Reaction: HNO₃ + NaOH → H₂O + NaNO₃ (1:1 ratio) If 2.0 mol NaOH exists, it requires exactly 2.0 mol HNO₃. But only this amount may be available—assuming supply matches, NaOH is fully consumed at 2.0 mol.

- Step 4: Check HNO₃ availability Suppose HNO₃ supply is 2.5 mol.

Required 2.0 mol < 2.5 mol—NaOH is truly limiting.

- Step 5: Compute theoretical product 1 mol NaOH → 1 mol H₂O. Thus, 2.0 mol NaOH yields 2.0 mol H₂O. In g: 2.0 mol × 18 g/mol = 36 g H₂O.

Real-World Implications: Why Limiting Reagent Matters Beyond the Lab

In industrial chemistry, limiting reagent calculations dictate raw material procurement, waste control, and process economics. A pharmaceutical plant synthesizing a drug must precisely dosed reagents to maximize yield and minimize byproduct formation. During a 2023 BASF report, engineers cited limiting reagent analysis as critical to reducing waste by 12% in a key API synthesis.大学化学实验室虽然看似“理论”,但其核心逻辑—控制 reagents before reaction completion—resonates deeply in professional settings. Resource constraints demand that every gram count, shaping cost-efficiency and sustainability. As chemist Dr.

Elena Moreau notes: “Limiting reagent problems train scientists to prioritize precision. In a lab or factory, this means saving materials, time, and reducing environmental impact.”

The skill sharpened here—analyzing reagent constraints—fuels innovation across chemistry’s spectrum: from vaccine development to materials science. Each problem enforces that mastery means recognizing not just what reacts, but what runs out.

Related Post

Unlock Market Mastery: Precision Trading with Arc MyChart Data Visualization

Adidas Vietnam: The Full Price Trail of Authentic Sepatu — How Much Do You Really Pay?

Unlock Compassionate Outreach with Find Relentless Church Email: Your Gateway to Mission-Critical Connections

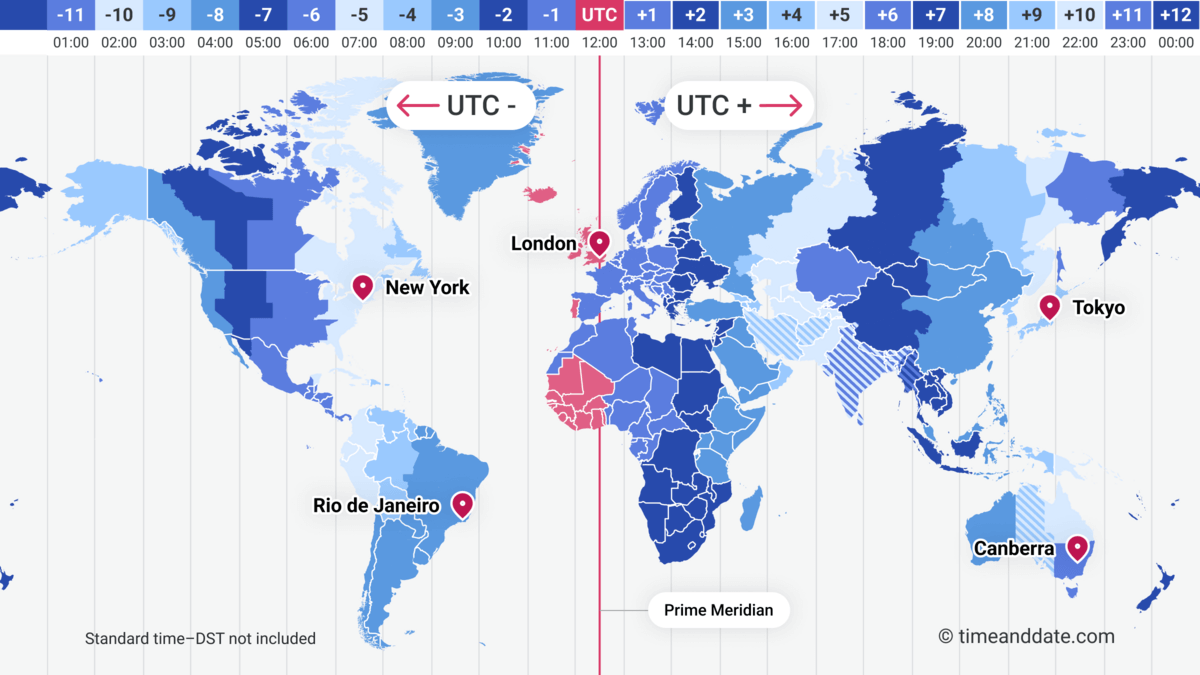

Inside Alaska’s Time Zone: How the Last Frontier Dives Into UTC−9 and Sits Ahead of the World Clock