Molecular Blueprints: Unraveling the Core Elements of Nucleic Acids

Molecular Blueprints: Unraveling the Core Elements of Nucleic Acids

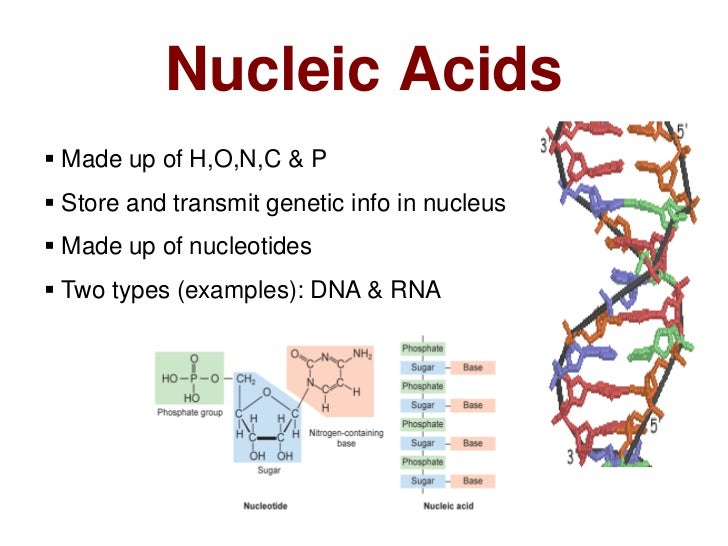

At the heart of every living cell lies a hidden language written in the language of nucleic acids—DNA and RNA. These complex molecular structures serve as the foundation of genetic information, guiding everything from inherited traits to daily cellular functions. Their intricate architecture, governed by precise chemical principles, encodes life’s blueprint and enables the dynamic processes that sustain biology.

Understanding the core elements of nucleic acids reveals not only how genetic code is formed but also how evolution, disease, and biotechnology converge through the dynamics of these remarkable molecules.

The Dual Identity of Nucleic Acids: DNA and RNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA) are the two primary forms of nucleic acids, both composed of nucleotide monomers linked in long chains through phosphodiester bonds. While structurally similar, they serve distinct biological roles.DNA stores and transmits genetic information across generations, functioning as the cellular analog of biological software. Its double-helical structure—first described by Watson and Crick—protects genetic code while enabling precise replication and repair. RNA, in contrast, operates as a functional messenger and catalyst.

Unlike DNA, most RNA molecules exist as single strands, allowing them greater structural flexibility. Critical roles include translating DNA’s instructions into proteins, regulating gene expression, and forming catalytic cores in ribozymes. As Francis Crick once noted, “RNA is not just a passive copy—its active participation reshapes how we view life’s molecular machinery.” This distinction underscores the specialized functions that distinguish these two nucleic acid types.

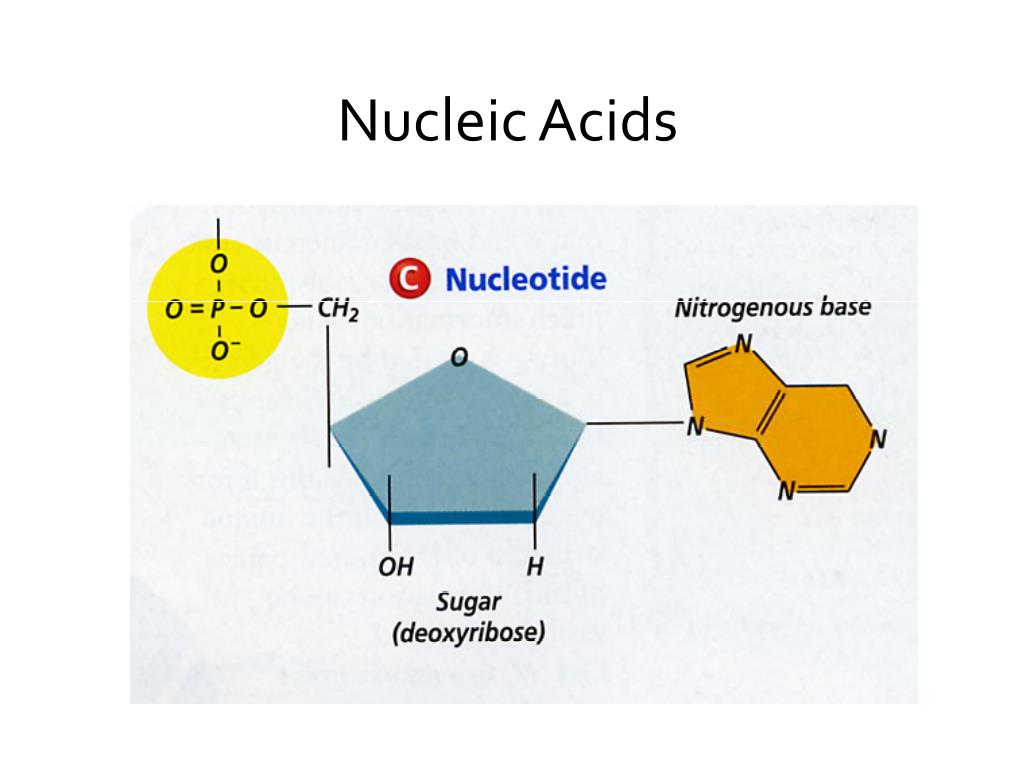

Decoding the Nucleotide: The Building Blocks of Genetic Code

Every nucleic acid is assembled from nucleotides—complex molecules composed of three key components: a nitrogenous base, a phosphate group, and a sugar moiety. The nitrogenous bases fall into two categories: purines (adenine and guanine), which feature a double-ring structure, and pyrimidines (cytosine, thymine in DNA, and uracil in RNA), with a single-ring configuration. This complementarity allows precise base pairing—adenine with thymine or uracil, and cytosine with guanine—forming the rungs of the nucleotide ladder.The sugar in DNA is deoxyribose, partially lacking an oxygen atom to reduce reactivity and enhance stability. In RNA, ribose contains this hydroxyl group, facilitating dynamic conformational changes essential for its catalytic and regulatory roles. The phosphate group links nucleotides via 5’ to 3’ phosphodiester bonds, creating a sugar-phosphate backbone that confers structural integrity while allowing flexibility for processes like transcription and replication.

Each nucleotide’s distinct identity and arrangement ensures the accurate storage and expression of genetic information, illustrating how molecular simplicity underpins life’s complexity.

Structural Architecture: From Strands to Three-Dimensional Shapes

The molecular architecture of nucleic acids unfolds across multiple levels. At the primary structure, individual nucleotides are linked end-to-end through phosphodiester bonds, forming long homopolymeric or heteropolymeric chains.The secondary structure emerges as specific base pairing—guided by hydrogen bonding—drives the formation of the iconic double helix in DNA. This right-handed helix features antiparallel strands twisted around a central axis, stabilized by base stacking and electrostatic interactions between phosphate groups. RNA folds into intricate three-dimensional conformations driven by internal base pairing, enabling it to fold into intricate stem-loops, pseudoknots, and tertiary interactions.

These dynamic shapes are not random but evolutionarily optimized to perform specific biological tasks, such as enzyme catalysis or targeted gene silencing. The structural diversity enabled by nucleic acid folding illustrates a remarkable adaptability central to cellular function and regulation. “Cómo estructuras secundarias permiten que el RNA explore múltiples conformaciones y realice funciones catalíticas – algo atribuido principalmente a su flexibilidad estructural,” 분석a el bioquímico Thomas Cech, ganador del Premio Nobel.

Furthermore, nucleic acids self-assemble with computational precision. In DNA, complementary base pairing ensures faithful replication and transcription, with DNA polymerase and other enzymes acting as molecular architects. In RNA, transient secondary structures guide self-cleavage, localization signals, and ribosome binding—processes critical for post-transcriptional regulation.

These structural hierarchies exemplify how molecular form enables biological function, showing nucleic acids as dynamic, responsive entities rather than static molecules.

Genetic Code and Information Flow: From Nucleotides to Life Processes

The sequence of nitrogenous bases along a nucleic acid chain encodes the genetic instructions that direct all cellular activities. This information flows through central dogma pathways—DNA to RNA to protein—each step dependent on the fidelity and specificity of molecular interactions.DNA acquisition, replication, and repair form the foundation of genetic continuity, mediated by enzymes like helicases, polymerases, and ligases. Transcription converts DNA sequences into precursor RNA transcripts, enabling gene expression. RNA then undergoes splicing, capping, and polyadenylation to mature before directing protein synthesis during translation.

Conversely, RNA molecules such as microRNAs and siRNAs fine-tune gene expression by binding complementary sequences, silencing unwanted mRNAs. “Nucleic acids are not passive templates but active regulators of life, shaping development, adaptation, and disease through both coding and non-coding RNA networks,” explains geneticist Emily Hatlen. This dual capacity underscores their role as central mediators between genome and phenotype.

Errors in nucleic acid structure or sequence underpin countless genetic disorders and cancers, emphasizing their importance in health and therapeutics. RNA’s catalytic capabilities further expand nucleic acids’ functional range. Ribozymes—RNA molecules with enzymatic activity—drive spliceosome assembly and peptide bond formation, revealing RNA’s primordial role as both genetic carrier and catalytic agent in early evolution.

In clinical research, engineered nucleic acids power gene therapy, mRNA vaccines, and CRISPR-based genome editing, revolutionizing medicine. These advances highlight nucleic acids as dynamic, programmable tools capable of precise, targeted intervention.

The Role of Nucleic Acids in Evolution and Biotechnology

Beyond cellular function, nucleic acids are the raw material of evolution.Mutations, insertions, deletions, and recombinations within DNA sequences generate genetic variation, serving as the substrate for natural selection. Over generations, these molecular alterations drive adaptation and speciation, embodying the principle that “life flows through the strands of nucleic acids.” Comparative genomics reveals conserved sequences across species, linking molecular evolution to shared ancestry and adaptive innovation. In biotechnology, nucleic acids enable transformative tools.

DNA sequencing technologies decode genomes with unprecedented speed, unlocking insights into health, ancestry, and disease. Recombinant DNA technology allows precise gene cloning and expression, fueling insulin production and biopharmaceutical development. RNA interference and mRNA nanotechnology offer novel therapeutic strategies, leveraging nucleic acid design to modulate biological pathways.

Emerging fields like synthetic biology push nucleic acid engineering further, constructing artificial genes, genetic circuits, and minimal genomes. These advances challenge traditional notions of life, demonstrating nucleic acids’ versatility as both information carriers and programmable molecular systems. The integration of nucleic acid science into medicine, agriculture, and environmental management reflects its central role in shaping the future of science and society.

Toward a Deeper Understanding: The Enduring Significance of Nucleic Acids

Elements of nucleic acids constitute the foundational language of biology, encoding life’s complexity through chemical precision and structural elegance. From DNA’s genetic archive to RNA’s dynamic regulation, these molecules drive replication, expression, and innovation at every biological scale. Their architecture, sequence specificity, and functional diversity enable life to unfold with remarkable fidelity and adaptability.As research continues to reveal new dimensions of nucleic acid behavior—whether in gene regulation, epigenetic modification, or synthetic systems—the story of nucleic acids remains central to understanding life’s molecular basis and harnessing its potential for science and medicine.

Related Post

The Chemical Backbone of Life: Decoding the Essential Elements of Nucleic Acids

Taylor Lorenz Husband: Navigating Love, Identity, and the New Frontiers of Marriage

Protein Yang Kita Perlukan Dapat Diperoleh Dari 9 Makanan Tinggi Murah – Kampus Kabarmu Hidup Kamu Biasa da Silva

Beyond the Spotlight: Aminah Nieves, The Rising Star Redefining Modern Entertainment