Sanitary Landfill: How Modern Waste Disposal Safeguards Cities and Ecosystems

Sanitary Landfill: How Modern Waste Disposal Safeguards Cities and Ecosystems

In an era of rapid urbanization, effective waste management remains a critical challenge for cities worldwide. Among the most widely adopted solutions, sanitary landfills distinguish themselves as engineered, sanitized disposal systems that minimize environmental and public health risks. Far from open dumps, these environmentally regulated facilities transform waste handling into a controlled process—protecting groundwater, reducing pollution, and supporting resource recovery.

Understanding sanitary landfills—how they operate, what benefits they deliver, and the intricate steps enabling their function—is essential for sustainable urban development.

Defining Sanitary Landfill: More Than Just a Dump

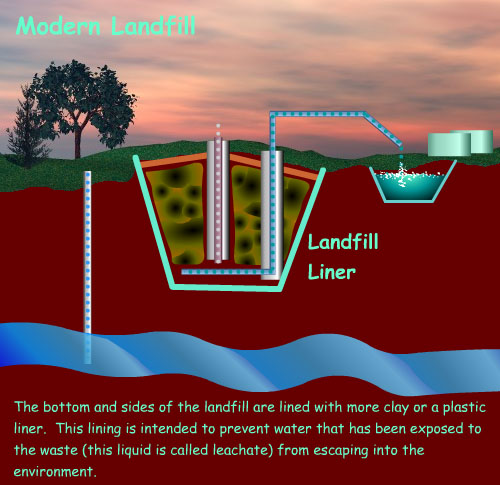

A sanitary landfill is a meticulously planned and monitored site designed to contain and manage solid waste in a way that prevents contamination of soil, water, and air. Unlike traditional open dumps—characterized by uncontrolled disposal, leachate runoff, and methane emissions—sanitary landfills incorporate multiple protective barriers and engineering controls.According to the International Solid Waste Association (ISWA), “A sanitary landfill is a engineered system where waste is deposited in a way that maximizes containment, controls leachate and gas, and ensures long-term environmental safety.” These facilities follow strict regulatory standards that define their structure, operation, and post-closure care. Key technical components distinguish sanitary landfills: - **Pre-treatment processes**, including sorting and shredding, reduce volume and remove hazardous materials. - **Liners and leachate collection systems** prevent toxic fluids from seeping into groundwater.

- **Gas capture and management** systems collect methane and compress or burn it to energy, minimizing greenhouse gas emissions. - **Compaction and cover layers** stabilize waste layers, minimizing dust, pests, and pressure on the containment system. “Modern sanitary landfills are filtering, controlled ecosystems rather than static waste piles,” notes Dr.

Elena Marquez, environmental engineering specialist at the Global Waste Management Institute. “Every phase—from design to closure—is governed by science and regulation to ensure environmental integrity.”

Environmental and Public Health Benefits: A Major Leap Forward

The adoption of sanitary landfills delivers transformative benefits for urban ecosystems and human health. At the core, these facilities dramatically reduce contamination risks.Without proper liners and leachate systems, hazardous chemicals from batteries, electronics, and medical waste often seep into soil and contaminate drinking water. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reports that sanitary landfills with effective boundary controls reduce leachate infiltration by over 95%, drastically lowering the risk of groundwater pollution.

Equally impactful is the containment of methane, a greenhouse gas 25 times more potent than carbon dioxide. Landfills account for approximately 15% of anthropogenic methane emissions globally. Sanitary landfills mitigate this through passive or active gas recovery systems: captured methane is either flared to reduce emissions or converted into renewable energy.

The World Resources Institute highlights data showing that properly managed landfills can reduce methane output by up to 90%, turning a potent climate threat into a valuable energy source. Beyond emissions and contamination, sanitary landfills enhance public health by eliminating breeding grounds for disease vectors. Open dumps attract pests like rats and flies, spreading diseases such as leptospirosis and typhoid fever.

By containing waste in sealed cells and applying effective covering protocols, modern landfills suppress rodent activity and vector proliferation. This transformation supports community well-being and reduces public health burdens in densely populated areas.

The Operational Lifecycle: From Construction to Closure

The journey of a sanitary landfill spans decades and follows a rigorous sequence of operational phases, each critical to long-term safety and environmental protection.1. Site Selection and Preparation Choosing a suitable location involves geological, hydrogeological, and environmental assessments. Developers evaluate soil composition, depth to bedrock, proximity to aquifers, and seismic activity.

The site must support impermeable liners, prevent lateral contamination, and withstand long-term structural loads. “Site selection is non-negotiable,” warns Dr. Marquez.

“Poor geography can render even the best-designed landfill unsafe and costly to repair.” Only locations meeting stringent regulatory criteria proceed to construction. 2. Waste Acceptance and Pre-Treatment Not all waste suited for landfills enters unsorted.

Pre-treatment includes sorting recyclables, removing hazardous materials (batteries, chemicals), and shredding organic or bulky waste to improve density. This phase maximizes space efficiency and prevents damage to containment systems. Innovations such as automated sorting conveyor belts and sensor-guided separation technologies now enable precision recycling at intake points.

3. Controlled Deposition and Compaction Waste is deposited in horizontal cells, compacted with heavy machinery to minimize air pockets and settlement. Modern landfills use vertical compaction and customizable compaction ratios—often exceeding 1.7 to 1—ensuring dense, stable layers.

Real-time monitoring of compaction effort prevents uneven settling and structural weaknesses that could compromise the liner system. 4. Safety Systems and Environmental Controls Each landfill layer functions as a defense.

Above-ground, impervious geomembranes or clay liners prevent leachate migration. Beneath lies a composite liner system—typically a high-density polyethylene (HDPE) membrane paired with a gravel drainage layer—collecting and redirecting leachate to treatment facilities. Active gas collection systems, comprising a network of wells and vacuum pumps, extract methane and input gases for energy or flaring.

These measures collectively form a multi-barrier defense designed to withstand centuries of use. 5. Post-Closure Monitoring and Care After waste placement ceases, landfills transition into monitored sites.

Engineers track leachate quality, gas compositions, and settlement patterns for decades—sometimes over a century. Liners may require repairs if breaches occur; gas systems are regularly maintained to prevent malfunctions. “Closure is not an end but a new beginning,” says Dr.

Marquez. “Ongoing stewardship ensures legacy sites remain safe for future generations.”

Sanitary landfills exemplify how industrial necessity and environmental responsibility can converge. Their layered structure, operational rigor, and advanced engineering render them far superior to historical waste disposal methods.

Yet, their true value emerges not only in containment—but in systemic transformation: reducing pollution, reclaiming energy, and protecting public health. As cities continue to generate ever-growing volumes of waste, the sanitary landfill stands as a cornerstone of sustainable urban futures, proving that responsible disposal is not a compromise, but a critical step toward resilience.

Related Post

Silaturahmi: The Heartfelt Bond of Trust, Its Spiritual Essence, and Lifelong Benefits in Islamic Teachings

Decoding Pemerintah Daerah: The Essence and Unmatched Value of Local Governance

Why Blockchain Must Be Embraced: Its Critical Benefits and Transformative Mechanism

PDA Dalam Hubungan: Pengertian, Manfaat, Dan Batasannya