Superficial vs Deep Anatomy: Decoding the Hidden Layers of Human Structure

Superficial vs Deep Anatomy: Decoding the Hidden Layers of Human Structure

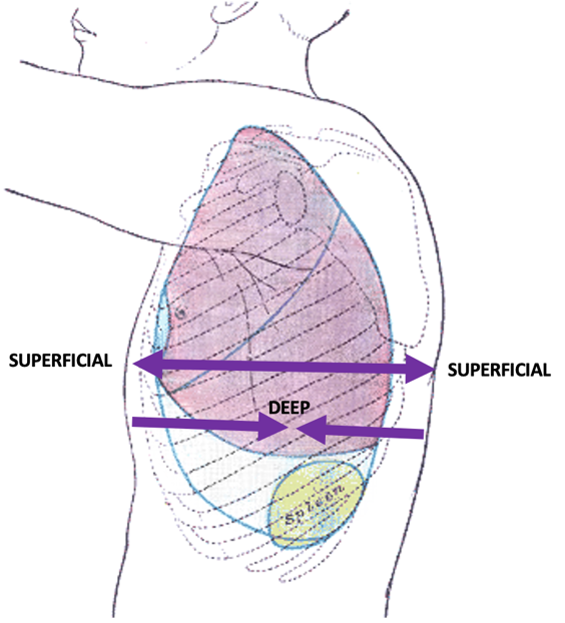

Understanding human anatomy demands more than memorizing muscle names or tracing nerve pathways—it requires a nuanced grasp of both superficial and deep anatomical layers, each critical in its own domain. While superficial anatomy offers a visible, accessible entry point—revealing the body’s outer contours and surface markers—deep anatomy uncovers the intricate systems operating beneath, from buried neural circuits to submerged vascular networks. This duality forms the foundation of clinical medicine, surgical precision, and diagnostic accuracy.

To navigate the complexity of human form, clinicians and students alike must master how superficial features map to—and diverge from—deeper realities, a distinction that shapes everything from patient assessment to specialized interventions.

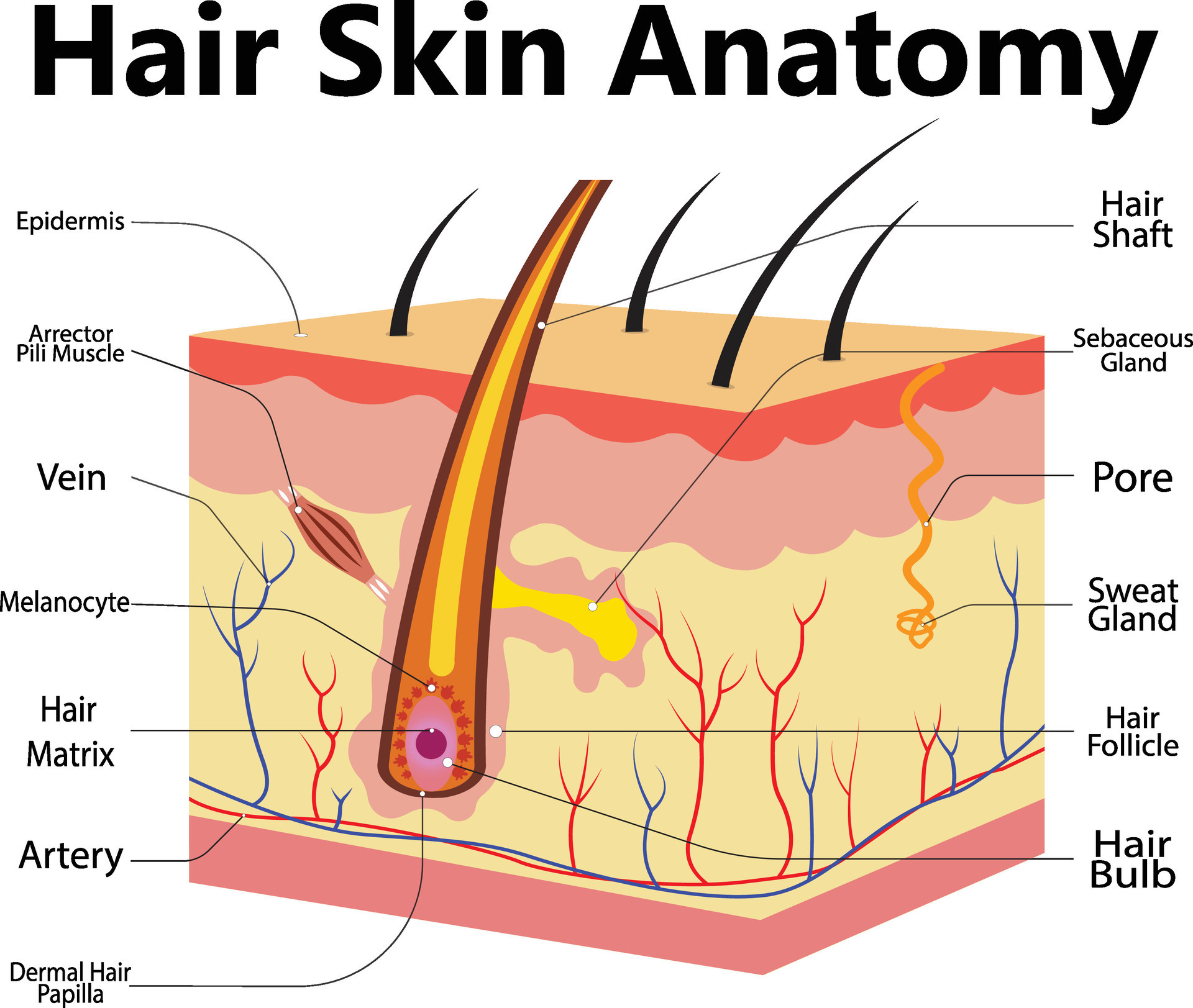

Superficial anatomy focuses on the body’s outer structures that are immediately observable, including skin, subcutaneous fat, muscles visible through the skin, tendons, and underlying fascia. These features cluster into recognizable zones—such as the antecubital fossa, cervical triangle, and inguinal triangle—each serving as a critical landmark in physical exams and landmark-based procedures.

The visibility of superficial anatomy makes it invaluable in fields like dermatology, emergency care, and aesthetic medicine, where surface conditions signal systemic health. Yet, superficial structures exist within a dense network of tissue that obscures underlying complexity.

Key superficial anatomical landmarks—like the linea alba, bony prominence, or vascular patterns—function as reliable cues for clinicians but offer only a surface-level narrative. “Surface anatomy is where diagnosis often starts,” explains Dr.

Elena Morrisey, anatomical scientist at Johns Hopkins. “It’s the first connection patients and providers make, but it rarely tells the full story.” For example, a swollen forearm may appear inflamed superficially, yet deep structures like the ulnar nerve or brachial artery could be the true source—emphasizing the limits of relying solely on visible signs.

The Deep Layer: Revealing the Invisible Architecture Beneath

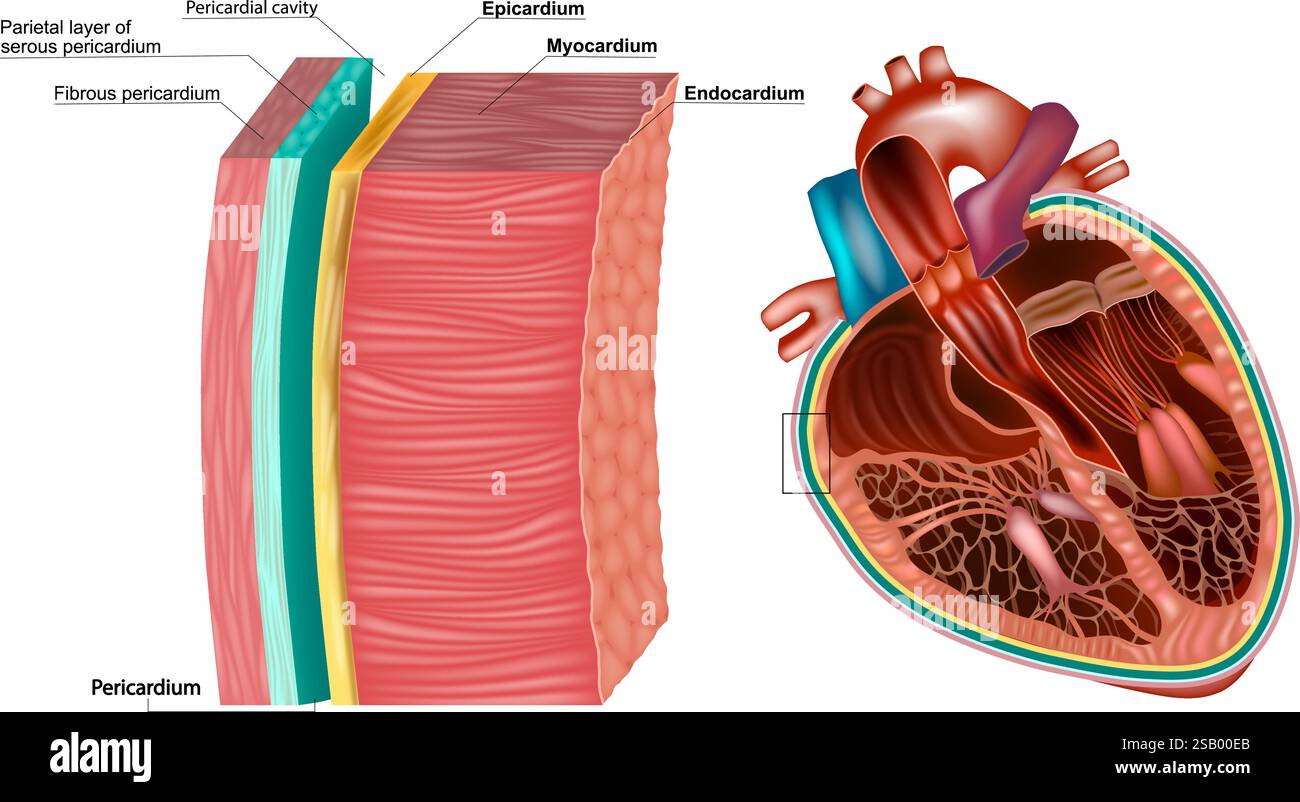

Beneath the surface lies deep anatomy—a realm defined by buried systems governed by neurovascular networks, fascia, and connective tissue embedded within muscular and skeletal frameworks. Deep anatomy lies beyond skin and subcutaneous fat, encompassing critical structures such as the brachial plexus, vertebral arteries, deep spinal ligaments, and the intricate innervation of aponeuroses.This domain is less about appearance and more about functional relationships: how nerves fan beneath muscle, how arteries branch through layers, and how fascia compartmental organs and limits movement.

Central to deep anatomy is the concept of fascial compartments—dense, fibrous layers that separate functional units within the body. “Fascia isn’t just passive tissue; it’s dynamic, transmitting forces and shaping movement,” notes Dr.

Rafael Alvarez, a surgical anatomist specializing in minimally invasive techniques. “Understanding these compartments is essential to preventing compartment syndrome or performing precise mobilizations.” For instance, the anterior compartment of the thigh contains the quadriceps muscle and deep extensor tendons, protected by the fascia lata but vulnerable to pressure buildup—a risk missed without awareness of deep structural boundaries.

Vascular and neural depth further complicate this picture.

Major arteries like the femoral and popliteal lie deep to superficial layers, their locations predictable but their spatial relationships critical in trauma or vascular grafting. The deep branches of the brachial plexus, emerging from C5 to T1, follow complex pathways through bone and muscle, guiding nerve conduction and clinical tests like reflex assessment. Without appreciation of these hidden pathways, interventions from injections to orthopedic surgery risk inefficiency or injury.

Mapping the Relationship: From Surface to Structure and Back

The interface between superficial and deep anatomy forms a dynamic spatial dialogue, where upper layers often indicate or constrain deeper function.The cervical spine’s bony landmarks, visible externally, dictate the depth and orientation of neural foramina—holes through which spinal nerves exit, influencing disorders like thoracic radiculopathy. In the abdomen, superficial muscle groups such as the external oblique mirror the deep transversus abdominis, forming a functional corset that protects internal organs and stabilizes movement—an elegant example of form following function across layers.

Surface anatomy also relies on deep structures for context.

The dorsal palmar crease, a superficial fold in the hand, aligns with the deep flexor digitorum profundus tendons beneath. Misinterpreting superficial contours without considering deep embryology or biomechanics can lead to misdiagnosis; for example, a deep neuroma in the hand may mimic superficial ganglion cysts, misleading in both imaging and treatment planning. Precision demands integration: knowledge of where a subcutaneous bump ends and where a branching nerve or vessel begins.

Modern imaging technologies, such as MRI and ultrasound, bridge this gap by visualizing both superficial and deep anatomy in real time, validating clinical landmarks while revealing hidden intricacies.

In interventional radiology, ultrasound-guided catheter placement depends on correlating superficial skin markers with deep vessel depth, minimizing risk and improving accuracy. Similarly, laparoscopic surgery hinges on distinguishing superficial layers from embedded visceral structures via depth perception and tactile feedback—an ability honed through deep anatomical understanding.

Clinical Implications: When Deep Knowledge Meets Surface Reality

In emergency medicine, a trauma patient’s torn meniscus may appear superficial, but its rupture often disrupts deep profundis muscle attachments and ulnar collateral ligaments—features not visible on initial exams but crucial for prognosis and repair. During orthopedic procedures, surgeons map superficial skin incisions against underlying bone, muscle, and neurovascular bundles to preserve function while repairing damage.In physical therapy, addressing superficial tightness without resolving deep fascial adhesions or restricted joint mechanics often results in only temporary relief; “Surface fixes mask deeper dysfunction,” warns Dr. Alvarez. “A holistic view is

Related Post

Econ Job Rumors Thrive on the Anonymous Omic Market Forum—Who’s Spearheading the Push?

Washington, D.C.’s 1300 D St SW: A Historic Epicenter of Policy and Prestige

9am Ist To Est

Unveiling the Secrets to Fitness Success: What Really Works Beyond the Hype