The Atomic Grip That Shapes Matter: Unraveling Bonding Chemistry

The Atomic Grip That Shapes Matter: Unraveling Bonding Chemistry

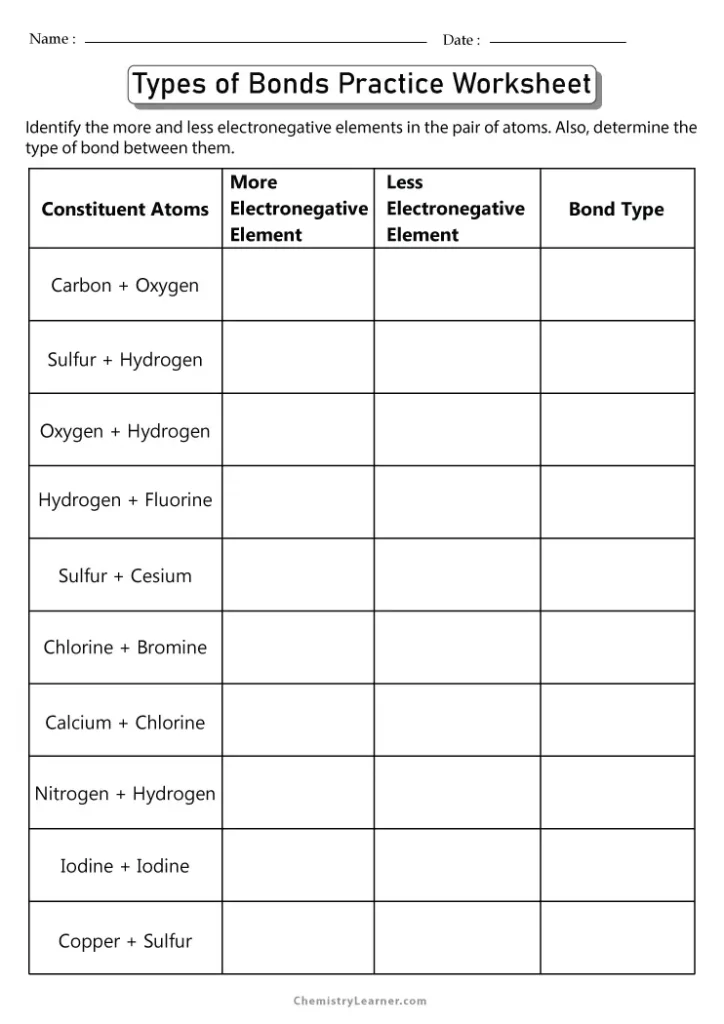

At the microscopic level, the stability, structure, and function of all known matter derive from a fundamental force: chemical bonding. Defined as the interaction between atoms that results in the formation of molecules or extended crystalline networks, bonding chemistry lies at the heart of chemistry, materials science, and biology. It governs everything from the way water molecules cling to each other to the robust strength of diamond’s carbon tetrahedral lattice.

Understanding bonding chemistry is not just a theoretical pursuit—it is the cornerstone of innovation in pharmaceuticals, nanotechnology, energy storage, and sustainable materials. ### The Core Definition: What Is Chemical Bonding? Chemical bonding refers to the forces that attract atoms to one another, enabling them to form stable molecular assemblies.

At its core, bonding arises from the quantum mechanical behavior of electrons—specifically their placement in atomic orbitals and their tendency to minimize energy states. When atoms approach each other, electrons are redistributed, creating regions of net attraction. This redistribution modifies electron density, forming what scientists describe as electrostatic and quantum fields that bind atoms into compounds.

Multiple types of bonds exist, each with distinct electron interactions and energy profiles. The most familiar include: - **Covalent bonds**: Shared electron pairs between atoms, as seen in organic molecules like methane (CH₄) or water (H₂O). These bonds typically form between nonmetals seeking stable electron configurations.

- **Ionic bonds**: Electrostatic attractions between oppositely charged ions, such as sodium chloride (NaCl), where sodium donates an electron to chlorine. - **Metallic bonds**: A unique cluster of interactions where valence electrons are delocalized across a lattice of metal atoms, conferring conductivity and malleability—qualities that distinguish metals from other materials. Each bond type follows principles rooted in orbital theory, electronegativity differences, and energy minimization, collectively defining the three-dimensional architecture of matter.

The Anatomy of Bond Formation: Quantum Foundations

The emergence of chemical bonds can be traced to quantum mechanics, particularly the Schrödinger equation and molecular orbital theory. When two atoms draw near, their atomic orbitals overlap, generating molecular orbitals where electrons are shared or transferred. Constructive interference forms bonding orbitals at lower energy, while destructive interference produces antibonding orbitals, raising energy levels.Bonding arises when electrons occupy stabilizing, in-between energy states—rejected orbitals remain empty. “This quantum dance of electrons,” explains Dr. Elena Torres, a physical chemist at ETH Zurich, “dictates whether atoms stay apart or unite into compounds.

The balance between attractive and repulsive forces determines bond strength and geometry.” Central to this process is electronegativity—the tendency of an atom to attract electrons. Within a bond, unequal sharing shifts electron density toward the more electronegative atom, generating polarized dipoles. Such polarization influences reactivity, solubility, and interaction with light or other molecules.

Understanding these quantum underpinnings allows scientists to predict bonding behavior with precision.

Primary Bonding Types and Their Implications

Covalent bonds, formed by overlapping orbitals rich in shared electrons, define molecular integrity in compounds from antibiotics to polymers. These bonds vary in strength and geometry—sp³ hybridization in methane leads to tetrahedral alignment, while double bonds in ethylene (C₂H₄) permit rotation and enable polymerization.Ionic bonds, arising from electron transfer, dominate salts and crystalline solids, forming rigid, high-melting lattices. Yet they reveal nature’s elegance: sodium chloride’s 1:1 ratio of Na⁺ and Cl⁻ ions crystallizes in a face-centered cubic structure, maximizing stable electrostatic interactions. Metallic bonding defies traditional electron sharing.

Here, valence electrons form a “sea” moving freely through positive ion cores, explaining metals’ conductivity, malleability, and luster. This cohesion enables flexible structures—from copper wiring to gold jewelry—without brittleness. Advanced bonding models extend beyond elementary categories.

Hydrogen bonding, though weaker, shapes biology: it stabilizes DNA double helices and directs protein folding. Van der Waals forces—temporary dipoles from electron fluctuation—govern molecular recognition in drug-receptor binding and phase transitions. Each bonding type, defined by electron dynamics and energy landscapes, tailors material properties and biological function.

The Spectacle of Bonding: From Nanotechnology to Life Itself

Bonding chemistry underpins breakthroughs across scientific domains. In nanotechnology, controlled covalent or non-covalent interactions guide self-assembly, enabling precise nanostructures with applications ranging from targeted drug delivery to quantum computing. Graphene’s extraordinary strength stems from its sp²-bonded honeycomb lattice—each carbon atom covalently linked via delocalized π-electrons, creating an ultra-strong, flexible sheet.In materials science, understanding bonding allows the design of smart alloys, high-temperature superconductors, and flexible electronics. For example, perovskite solar cells leverage tailored ionic and covalent bonding to achieve high light absorption and charge mobility, pushing renewable energy efficiency. Biologically, bonding defines life.

Hydrogen bridges between nucleotide bases in DNA enable replication; peptide bonds form peptide chains in proteins, dictating enzymatic activity and cellular architecture. Metalloprotein bonds—such as iron-heme clusters in hemoglobin—enable oxygen transport with remarkable specificity. Quantifying bonding strength, geometry, and electronic effects allows researchers to engineer molecules with tailored reactivity, stability, and function, forging links between atomic structure and macroscopic innovation.

Ongoing Revolution: Predicting and Engineering Bonds

Modern computational tools now simulate bonding at quantum levels, accelerating discovery. Density functional theory (DFT) and machine learning models predict bond formation, reactivity, and material properties with unprecedented accuracy. These advances enable “bottom-up” design—constructing novel compounds from first principles.Recent breakthroughs include single-atom catalysts, where individual metal atoms bond selectively to support molecules, drastically improving reaction efficiency. Machine-designed polymers mimic natural structures, exhibiting enhanced durability or responsiveness. Originally defined by electron behavior, chemical bonding continues to evolve from observed phenomenon to engineered science.

“Bonding is no longer just studied—it’s anticipated,” asserts Dr. Rajiv Mehta, computational chemist at MIT. “We’re shifting from passive observation to active design, respriting nature’s rules to build materials with besp

Related Post

Alf Casting: The Transformative Force Reshaping Modern Design Via Precision and Artistry

Cha Soobin: Architect of Korean Modernity in Photographic Visualism

Net Worth Vivica Fox: Hollywood Star Behind $50M Legacy and Persistent Stardom

Honda CR-V Diesel 2017: The Corvette of Compact Trails, Real-World Performance Across the Highway