The Fall of the Edict: How the Revocation of Nantes Redefined Religious Freedom in France

The Fall of the Edict: How the Revocation of Nantes Redefined Religious Freedom in France

When King Louis XIV formally revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685, he delivered a decisive blow to religious tolerance in France—marking a turning point in European history where state power suppressed minority faiths with ruthless finality. This act, often framed as the end of humane coexistence, transformed a fragile experiment in pluralism into a era of persecution, forcing hundreds of thousands of Huguenots—French Protestants—to flee or face annihilation. The revocation was not merely a political maneuver; it reflected deep-seated anxieties about sovereignty, loyalty, and the consolidation of royal authority in an increasingly centralized France.

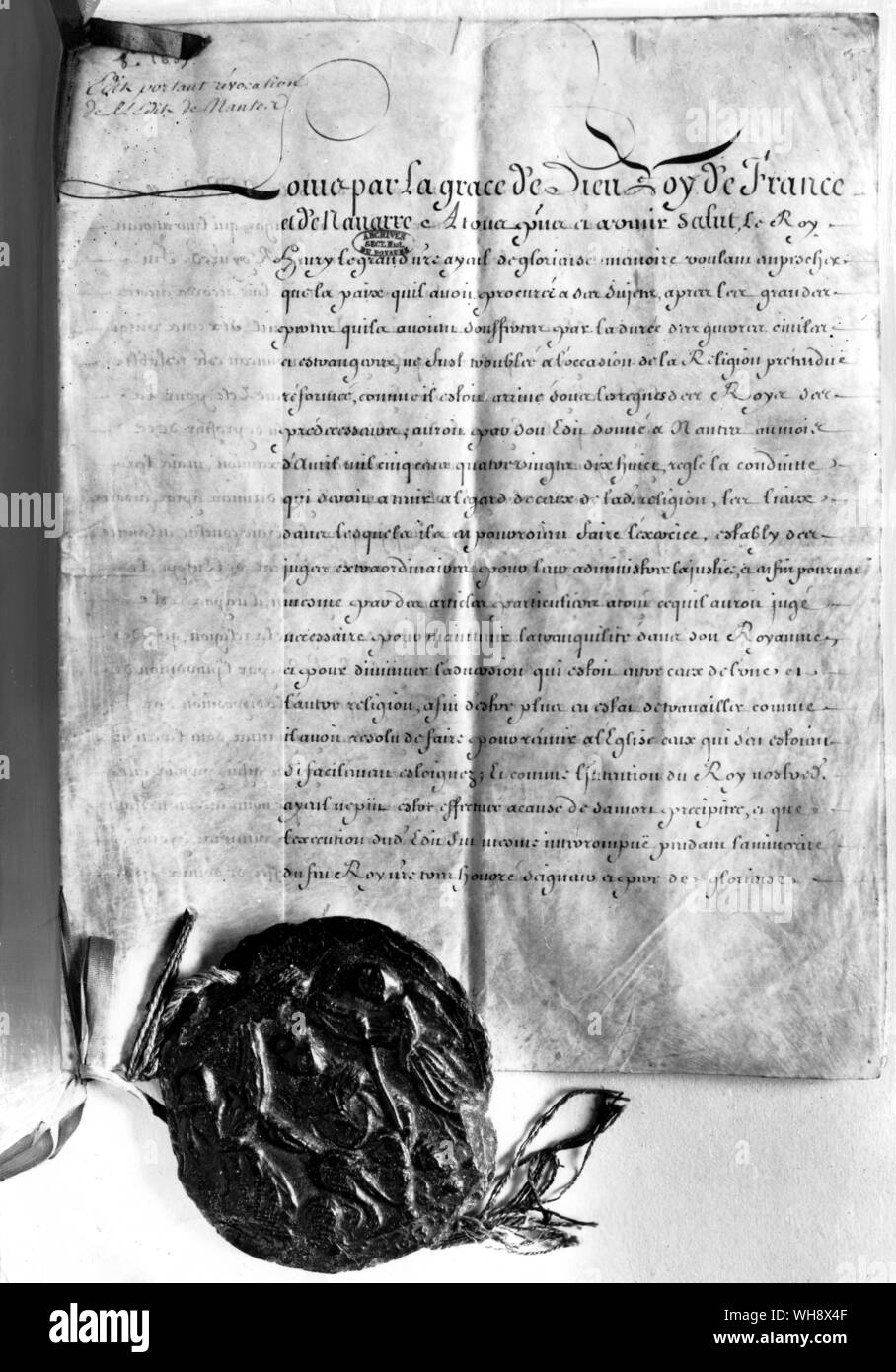

The Edict of Nantes, issued in 1598 by Henry IV, had granted Huguenots substantial rights to worship, hold public office, and govern their communities within a Catholic-majority kingdom. It was a pragmatic compromise born of decades of civil war, aiming to end the violence of the French Wars of Religion. As historian François Raspes notes, “The Edict was not a declaration of equality, but a carefully negotiated peace—a recognition that survival required mutual restraint.” For nearly a century, this fragile balance allowed moderate worship and civic participation for Protestant minorities, enabling a vibrant yet cautious coexistence.

Yet by the 1660s, Louis XIV’s vision for an absolute monarchy—centered on unity under Catholicism as a pillar of state power—clashed with that fragile equilibrium. Deeply committed to *un roi, une loi, une foi* (“one king, one law, one faith”), Louis pursued policies that increasingly marginalized non-Catholic worship. The king’s mistress, Madame de Maintenon, and strong advisors insisted that religious division posed a permanent threat to loyalty and order.

The path to revocation unfolded through escalating pressure: royal decrees restricting Protestant preaching, the forced conversion of Huguenot children, and the targeting of religious assemblies under the guise of enforcing orthodoxy. The dragonnades—dragoon-led house-to-house terror tactics—compelled public baptism through intimidation and brutality. By 1685, it became clear the Edict was no longer sustainable.

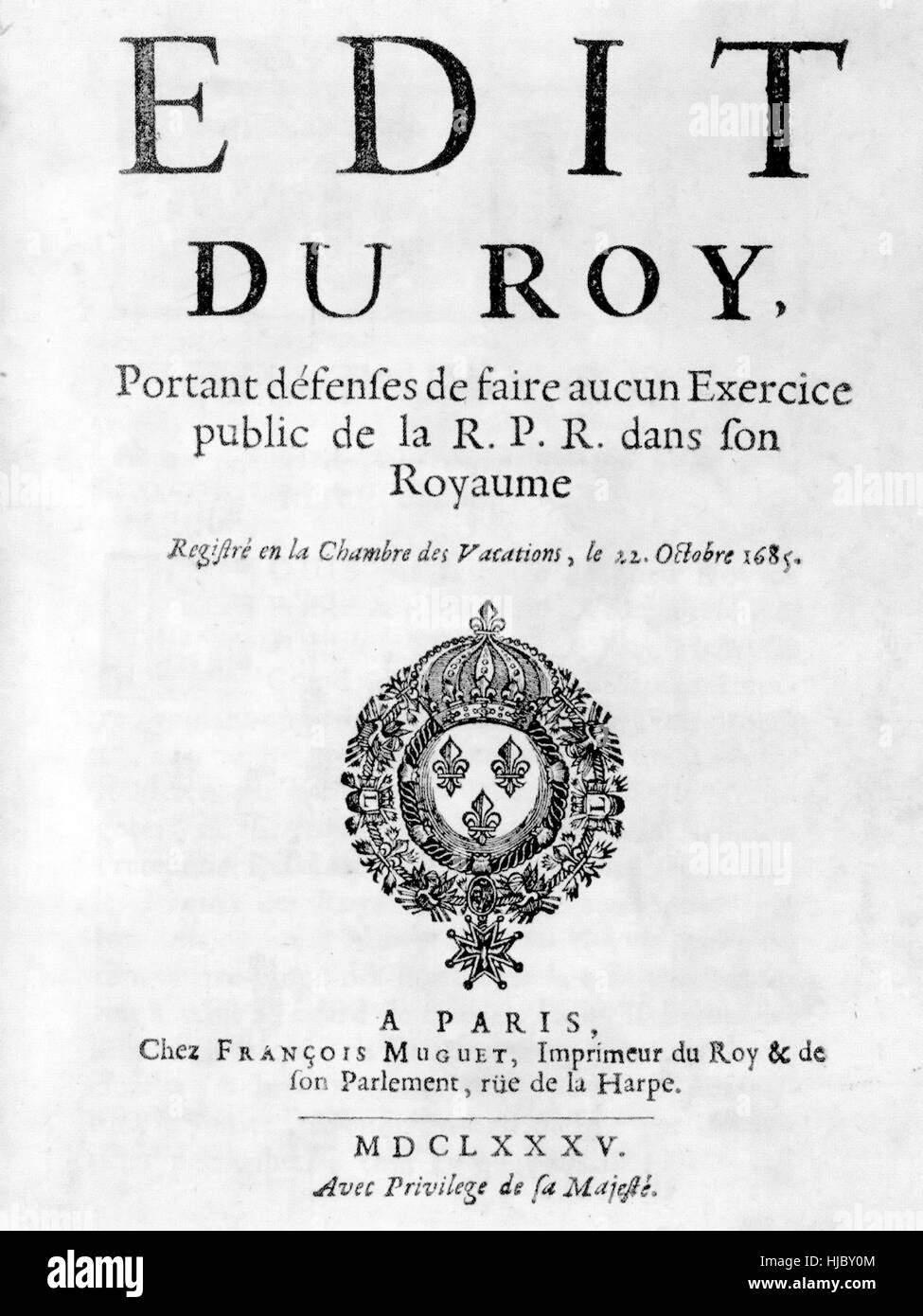

On October 22, Louis XIV issued the *Édit de Fontainebleau*, formally abrogating the Edict of Nantes. With it, Protestant worship was banned, Huguenot institutions dismantled, and pastors either exiled or imprisoned. Thousands faced torture, forced conversion, or execution; others fled across borders to the Dutch Republic, England, Prussia, and the American colonies—igniting a diaspora that reshaped global religious landscapes.

Contemporary accounts describe streets cleared of Protestant symbols: churches burned, Bibles destroyed, and congregations scattered like ash.

The Immediate Aftermath: Flight and Survival

The revocation triggered mass exodus: historians estimate between 200,000 and 400,000 Huguenots escaped France in the years following 1685. These survivors carried with them skills in textiles, banking, and craftsmanship—fields critical to Europe’s burgeoning economies.Cities such as Geneva, Rotterdam, and London welcomed them, eager to harness their talents while avoiding religious conflict at home. Meanwhile, France lost a significant skilled workforce; some estimates suggest the departure reduced its industrial and commercial potential by up to 10%.

Repression and Resistance: The Huguenot Response

Though outwardly subdued, Huguenot communities did not vanish.Underground worship persisted, often in remote villages or hidden homes, with clandestine pastors risking execution. Some secluded in fortified enclaves, while others smuggled Protestant texts across borders. In places like the Cévennes region, resistance briefly erupted in 1702 with the Camisard uprising—a violent protest crushed by royal forces but symbolizing enduring spiritual defiance.

The Edict’s revocation marked not just the end of tolerance, but a deliberate choice to subordinate religious identity to state control. Louis XIV justified the move with claims of national unity and divine right, asserting, “A believer cannot serve two masters—faith and rebellion,” a notion echoing broader absolutist ideology. Yet the policy backfired strategically: it alienated Protestant allies in Europe and weakened France’s long-term social cohesion.

Legacy and Historical Memory

Today, the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes stands as a stark warning about the costs of enforced uniformity. Scholars emphasize its role as a cautionary tale in the evolution of religious liberty—a turning point after which Europe’s trajectory toward pluralism would unfold slowly, through war, Enlightenment thought, and eventual human rights frameworks. As generations reflected on the tragedy, France’s reckoning with its past helped shape modern commitments to freedom of conscience.In remembering the revocation, we confront a defining moment: when a state’s will to homogeneity undermined the very stability it sought to secure. The memory of the Huguenots endures not only in archival records, but in the quiet resilience of communities scattered and the enduring principle that no faith deserves erasure. The Edict’s collapse did not end its influence; rather, it ignited a deeper understanding that tolerance is not concession—but the foundation of lasting peace.

Related Post

Unmatched Ego PC: The Ultimate Gaming Machine That Redefines Performance

Shh Or Shhh: The Correct Spelling That Quietly Dominates English

Download Instagram Stories on Your Desktop with Indownio — Speed, Simplicity, and Seamless Workflow

Zelensky Impeachment: The Unprecedented Political Crisis Shaking Ukraine’s Foundations