Understanding Mercury’s Molar Mass: The Key to Unlocking One of the Planet’s Most Enigmatic Elements

Understanding Mercury’s Molar Mass: The Key to Unlocking One of the Planet’s Most Enigmatic Elements

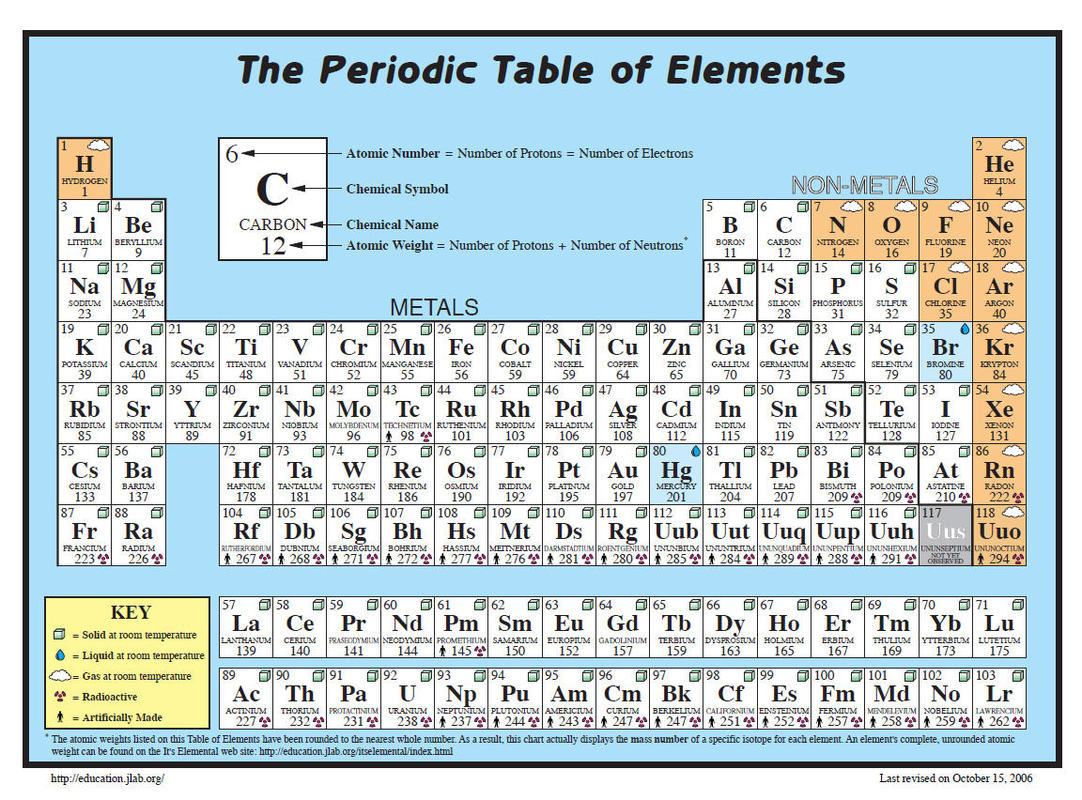

With a molar mass of precisely 200.59 atomic mass units (amu), mercury stands as a singular element in both chemical behavior and industrial importance. This relatively heavy metal, prized for its liquid state at room temperature, holds a unique position among the elements — not just for its physical properties, but for its role in science, medicine, and technology. Its molar mass, derived from the weighted average of its naturally occurring isotopes, reflects the subtle balance between stability and reactivity that defines mercury’s character in the periodic table.

Understanding this number unlocks deeper insights into mercury’s atomic structure, its isotopic distribution, and its behavior in both natural and engineered systems. Mercury’s atomic number is 80 — placing it in Group 12 of the d-block — and its electron configuration ends in [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s². But it is the molar mass — determined by the masses and relative abundances of its isotopes — that offers a quantitative foundation for studying its chemical and nuclear stability.

The dominant isotope, mercury-202 (204.98 amu), contributes significantly to the average, though the full natural spectrum includes lighter variants like mercury-198 (197.97 amu), intermediate isotopes, and rare heavy forms. “The precise measurement of mercury’s molar mass is critical not only for analytical chemistry but also for nuclear forensics and environmental monitoring,” explains Dr. Elena Torres, isotope geochemist at the Max Planck Institute.

“Small variations in isotope ratios can trace mercury’s environmental pathways, distinguish natural from anthropogenic sources, and inform public health strategies.” The molar mass of mercury is not a static value — it shifts slightly depending on isotopic composition, influenced by cosmic nucleosynthesis and terrestrial radioactive decay. The eight stable isotopes contribute to a weighted average reflecting their natural abundance. Mercury-198, the most prevalent (30.4% abundance), stabilizes the overall value, while mercury-200 (14.0% abundance) and mercury-202 (26.2%) anchor the heavier end.

This distribution reveals mercury’s origin in stellar fusion processes, where fusion reactions in dying stars forged heavy elements through nucleosynthesis. Mercury’s isotopic signature, therefore, acts as a fingerprint of cosmic alchemy. From a practical standpoint, mercury’s molar mass plays a vital role in precision science.

In laboratory mass spectrometry, accurate molar mass values enable identification and quantification of mercury species in complex matrices — whether in soil, blood, or industrial exhaust. This precision is indispensable in regulatory testing, clinical diagnostics, and pollution control. Nuclear Behavior and Stability: The Role of Molar Mass Mercury’s molar mass directly correlates with its nuclear stability and reactivity.

The low neutron-to-proton ratio in its lighter isotopes favors chemical complexity, while the heavier isotopes exhibit tighter nuclear binding, influencing decay pathways and radiation hazards. The relatively long half-life of stable isotopes like mercury-198 contrasts with radioactive variants such as mercury-203 (half-life ~780 years), which pose persistent environmental risks. Industrial applications hinge on mercury’s predictable physical and chemical behavior — behavior that begins with its atomic weight.

In thermometers, switches, and fluorescent lighting, mercury’s phase transition and vapor pressure depend critically on molecular mass. Molar mass determines molecular weight, which in turn governs vapor pressure and volatility — factors that define safe handling and environmental release protocols. Environmental mercury contamination remains a global concern due to its bioaccumulation and neurotoxicity.

The molar mass is central to modeling mercury cycling through ecosystems. For instance, isotopic fractionation during microbial methylation — where lighter isotopes preferentially convert to methylmercury — leaves measurable isotopic signatures that trace contamination sources. Researchers rely on mercury’s precise molar mass to calibrate detectors, interpret mass spectra, and develop remediation strategies.

Sample Data: Isotope Mass and Natural Abundance Mercury’s isotopic composition and molar mass breakdown: - Mercury-198 (198.9834 amu, 26.2% abundance): Most abundant isotope, key to mass standardization - Mercury-200 (199.9839 amu, 14.0% abundance): Influences higher-end mass calculations - Mercury-202 (201.9688 amu, 30.4% abundance): Major contributor to average mass due to stable nuclear configuration - Mercury-199 (198.9658 amu, 18.0% abundance): Second most common isotope with distinct isotopic pattern Naturally, mercury lacks stable isotopes longer than mercury-198; all heavier isotopes are radioactive, decaying over geological timescales. This radioactive decay chain affects long-term environmental budgets and informs age-dating techniques in geochemistry. Mercury’s molar mass is not merely a number — it is a cornerstone of chemical identity.

From isotope analysis to industrial engineering

Related Post

Chiefs’ Trade Rumors At A Crossroads: Who Stays, Who Leaves in the Wr Trade Turmoil?

The Adriatic Campaign: Napoleon’s Naval Struggle for the Mediterranean Sea

Threshold Human Geography: When Physical Limits Shape Human Fate

Beverly Hills Cop 3 Cast: Still Ich bones to the Law, Decades Later