Unlocking Life’s Blueprint: How Prokaryotic Gene Expression Control Drives Survival and Adaptation

Unlocking Life’s Blueprint: How Prokaryotic Gene Expression Control Drives Survival and Adaptation

At the heart of microbial evolution lies a masterful system: the precise control of gene expression in prokaryotic cells. Organisms like bacteria and archaea—some of Earth’s oldest and most prolific life forms—respond to environmental shifts with remarkable speed and accuracy, thanks to tightly regulated genetic circuits. Rather than rigid blueprints, prokaryotes employ dynamic regulatory mechanisms that activate, suppress, or fine-tune gene activity in real time.This adaptive control enables them to thrive in fluctuating conditions, from nutrient scarcity to oxidative stress, making gene expression regulation a cornerstone of prokaryotic biology. Through frameworks like the Pogil model, students explore how molecular switches and signaling pathways orchestrate the delicate dance between DNA and function, revealing nature’s elegant solution to survival at the cellular level.

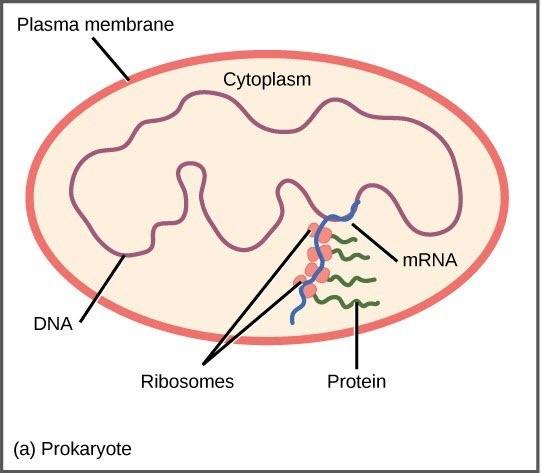

Prokaryotic gene regulation is distinguished by its speed, efficiency, and versatility—qualities essential for organisms without the complexity of eukaryotic nuclei. Unlike their eukaryotic counterparts, prokaryotes rely primarily on transcriptional control, where the initiation of RNA synthesis is the principal site of regulation.

This streamlined system allows rapid responses to external stimuli, often within seconds. Mechanisms include operons—clusters of functionally related genes co-regulated by a single promoter—serving as biological microprocessors. The most famous example, the *lac* operon in *Escherichia coli*, illustrates how gene clusters activate only in the presence of specific substrates like lactose, demonstrating precise metabolic efficiency.

Operons: The Genomic Command Centers

Operons represent the cornerstone of prokaryotic gene expression control. A functional operon consists of a promoter, operator, structural genes, and regulatory regions—allowing coordinated transcription of multiple genes. The *lac* operon, for instance, contains genes encoding β-galactosidase, permease, and transacetylase, all essential for lactose metabolism.Operon activity hinges on regulatory proteins that bind DNA in response to cellular signals. The *lac* repressor, a key player, binds tightly to the operator in the absence of lactose, blocking RNA polymerase and preventing transcription. When lactose is present, it binds the repressor, inducing a conformational change that releases the DNA—unlocking gene expression.

Conversely, in high glucose conditions, catabolite repression via cAMP-CAP complex ensures energy-efficient regulation. This system exemplifies how prokaryotes balance metabolic demands with environmental availability, minimizing wasteful gene activity.

Regulatory proteins are the molecular extensively workhorses of prokaryotic control systems.

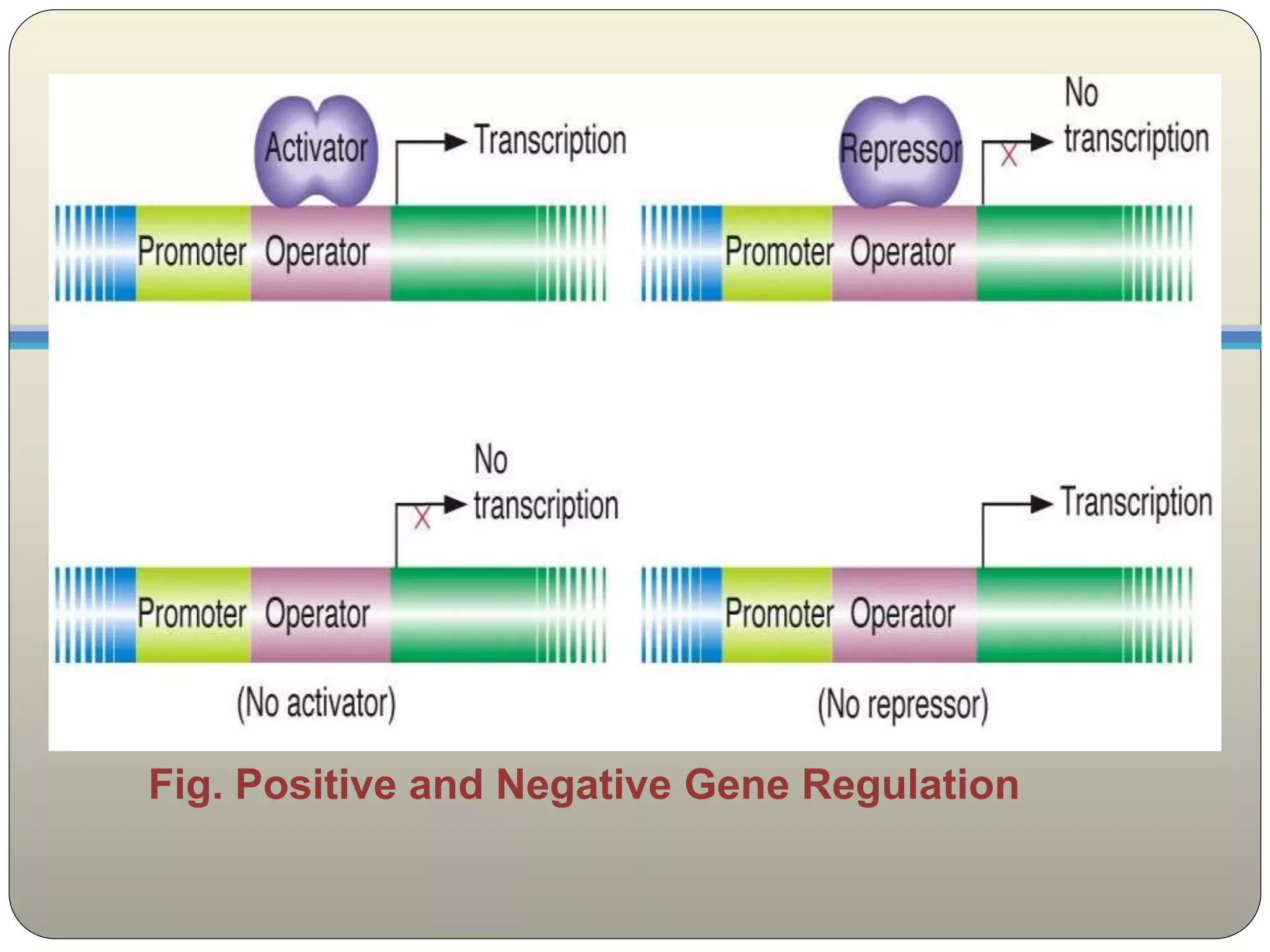

Activators and repressors respond to chemical cues, modulating transcription with remarkable specificity. Activators like CAP (catabolite activator protein) enhance RNA polymerase binding by recognizing cAMP signals, boosting expression during low glucose. Repressors, such as the lactose-borne LacI/G, enforce strict repression by physically obstructing transcription—only lifting upon inducer binding.

These proteins interface directly with DNA sequences via kissing loops or helix-turn-helix motifs, ensuring precise local control.

Environmental Sensing and Signal Transduction

Prokaryotes survive by sensing and adapting to their surroundings, and their regulatory systems are exquisitely tuned to environmental signals. Two-component systems (TCS) stand out as primary transducers of extracellular stimuli.These modular pathways consist of a sensor histidine kinase and a response regulator. The kinase autophosphorylates upon detecting signals like osmotic pressure or iron availability, transferring the phosphate to the response regulator. Activated regulators then modulate gene expression—either activating defense genes or repressing unnecessary functions.

Such systems enable rapid adaptation across environmental gradients, proving indispensable for pathogenicity and persistence.

Post-Transcriptional and Global Regulatory Layers

Beyond transcription, prokaryotic gene expression is refined at post-transcriptional and metabolic levels. Small regulatory RNAs (sRNAs) and riboswitches exert fine control without protein intermediates.Riboswitches, structured RNA elements in 5’ untranslated regions, alter conformation upon ligand binding—blocking or enabling ribosome access to mRNA. sRNAs, guided by Hfq proteins, base-pair with target mRNAs, influencing stability, localization, or translation. This rapid, protein-free control supports swift responses to stress or nutrient shifts.

Global regulatory proteins further coordinate large-scale cellular programs. Sigma factors, such as σ^32 in heat shock or σ^S in stationary phase, redirect RNA polymerase to stress-responsive promoters, altering the transcriptome en masse. RNA polymerase itself is regulated through subunit modulation and allosteric changes, ensuring context-specific activation.

Together, these layers create a responsive, adaptive network capable of managing complex environmental transitions with minimal genomic overhead.

Related Post

Mastering Fe Script in Roblox: Unlocking Unlimited Potential for Developers

Lake Havasu Zip Code 85341: The Turquoise Gateway to Arizona’s Desert Oasis

Sadie Sink’s Boyfriend: Decoding the Ubeck Relationship Behind the Headlines

RCB vs Pbks IPL 2024: A Clash of Traditions and Tactics Under the Lights