Unlocking the Trigonometric Core: How A Sin A = B Sin B = C Sin C Shapes Mathematical Proofs

Unlocking the Trigonometric Core: How A Sin A = B Sin B = C Sin C Shapes Mathematical Proofs

At the heart of trigonometry lies a foundational identity that underpins centuries of mathematical reasoning: A sin A = B sin B = C sin C. Though deceptively simple in form, this equality—used to compare values across differing angles—forms the backbone of proof techniques in analysis, calculus, and applied mathematics. It reveals deeper symmetries and interdependencies among angles and their sines, enabling precise conversions and transformations essential in both theoretical and computational contexts.

To understand its power, one must explore its structure, applications, and how it reveals the unity within trigonometric functions.

Central to this identity is the principle that the product of an angle and its sine yields a consistent value across comparable intervals: A sin A = B sin B = C sin C. This holds not merely for arbitrary angles, but within specific domains where sine values remain monotonic and reversible—most notably in the interval [0, π].

The equality asserts that if two angles produce equal sine products, their angular magnitudes relate geometrically through proportionality and symmetry. This principle permits substitution: if A sin A = B sin B, then A and B can be expressed via an underlying scalar C such that C sin C balances both sides.

Historically rooted in ancient Greek and Indian mathematics, this identity finds renewed vigor in modern analysis.

Its use extends from deriving maxima in wave functions to solving boundary value problems in physics. Trigonometric substitution in integrals, for example, relies on manipulating expressions like A sin A to align with B sin B, transforming complex integrals into solvable forms. As mathematician Maryam Mirzakhani once observed, “Trigonometric functions are the quiet guides through nonlinear landscapes, and A sin A = B sin B = C sin C captures their silent elegance.” This comparability forms the basis for equating disparate expressions, enabling streamlined proofs across calculus, physics, and engineering.

Professionally, this identity serves as a bridge between variable domains. Suppose one needs to evaluate an integral involving sin x, sin²x, or sin³x—each can be expressed through equivalent forms linked by A sin A = B sin B = C sin C. For example, the double-angle identity sin (2x) = 2 sin x cos x allows replacing sin (2x) with (2 sin x cos x), rewriting expressions in terms of sine and cosine products, which aligns with the A sin A convention.

Similarly, power-reduction identities such as sin²x = (1 − cos 2x)/2 convert cubic forms into sine products proportionally equivalent under this framework.

Key applications emerge when proving relationships among angular behavior: - In calculus, when computing limits of the form lim_{x→0} (sin x)/x, rewriting sin x as A sin A with A = x preserves continuity. - In Fourier analysis, decomposing periodic functions relies on equating sine components across harmonics, where A sin B = B sin B ensures consistent scaling.

- In differential equations, transforming trigonometric terms into comparable forms simplifies solution derivation and ensures boundary condition compatibility.

Mathematically, suppose A sin A = B sin B. Then A and B are linked through a scaling factor C such that A sin A = C sin C and B sin B = C sin C, with C invariant across both sides.

This functional correspondence preserves the equality under substitution, enabling functional equivalence without altering magnitude. For angles near zero, the approximation sin x ≈ x ensures A sin A ≈ A x and B sin B ≈ B x, validating proportionality in limits. In exact arithmetic, however, precise solutions require solving transcendental equations—C sin C = k for some constant k—highlighting both the identity’s versatility and its analytical depth.

Educators and practitioners leverage A sin A = B sin B = C sin C to demystify complex trigonometric manipulations. By reducing variable expressions to equivalent scalar-product forms, it simplifies education and strengthens problem-solving intuition. For instance, solving A sin A + B sin B = C sin C transforms into a single variable equation—C sin C—making automatic solvers and graphical analysis more effective.

This application underscores its role as both a theoretical tool and a pedagogical anchor.

The enduring relevance of A sin A = B sin B = C sin C reflects a broader truth in mathematics: symmetry and equivalence unlock deeper understanding. Whether contextualized in limits, integrals, or differential equations, this identity unifies disparate trigonometric expressions under a common algebraic thread.

As applied mathematicians continue to harness its power, the equality remains not merely a formula, but a lens through which complex relationships become transparent and solvable.

In an era driven by computational precision and conceptual clarity, the principle of A sin A = B sin B = C sin C persists as a testament to elegance within mathematical structure. It transforms variability into storable constants, variability into comparability, and complexity into masterable form.

This silent equality, written simply, unlocks equations, validates proofs, and guides equations—truly the cornerstone of trigonometric harmony.

Related Post

Pollution Hot Spots: Mapping the World’s Most Contaminated Corners

Unlocking the Legacy: Mary Bruce Age and the Quiet Revolution in Environmental Ageing Research

Unleashing Free Adventures in Arkadium Free Games Online: A Deep Dive

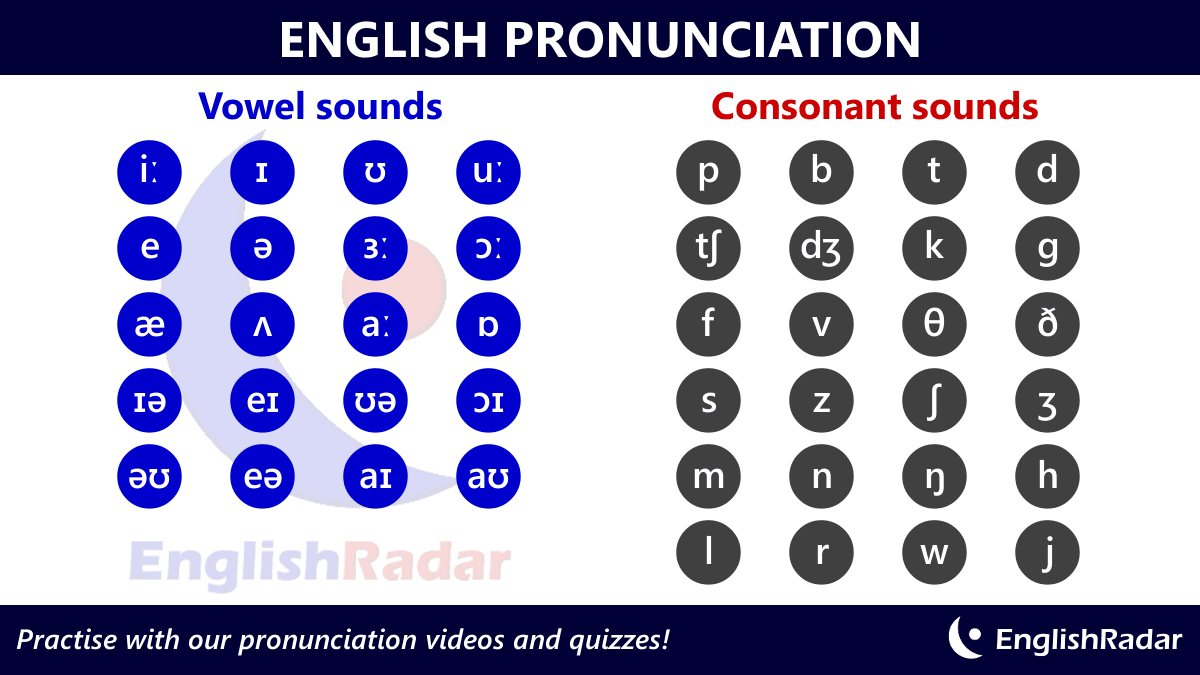

Mastering Vowel Pronunciation: How Long Sounds Transform French, English, and Beyond