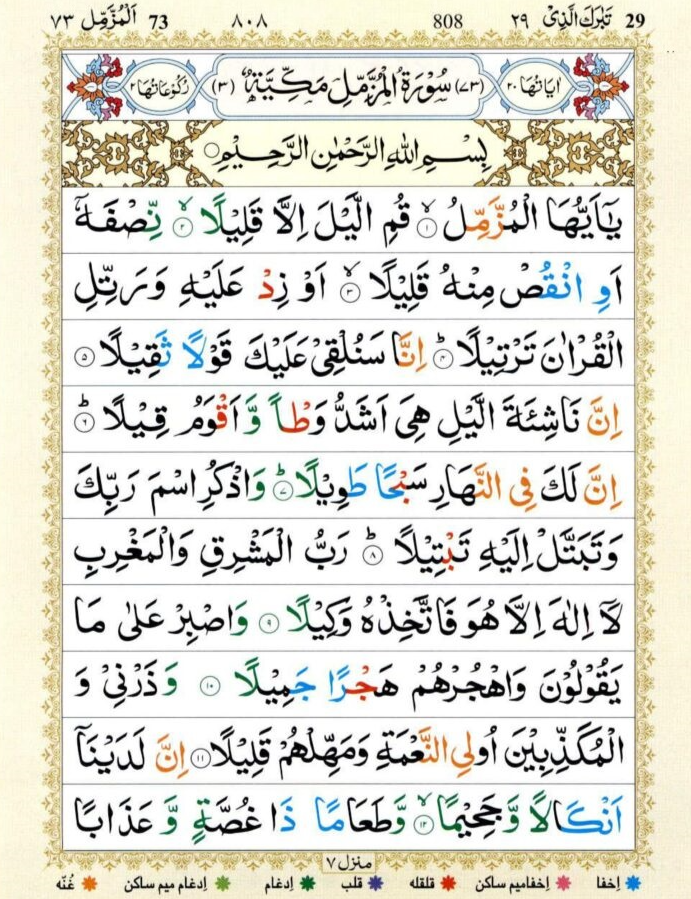

Unpacking Surah Al-Muzzammil (73:10): The Rentier’s Covenant Beneath the Shield of Protection

Unpacking Surah Al-Muzzammil (73:10): The Rentier’s Covenant Beneath the Shield of Protection

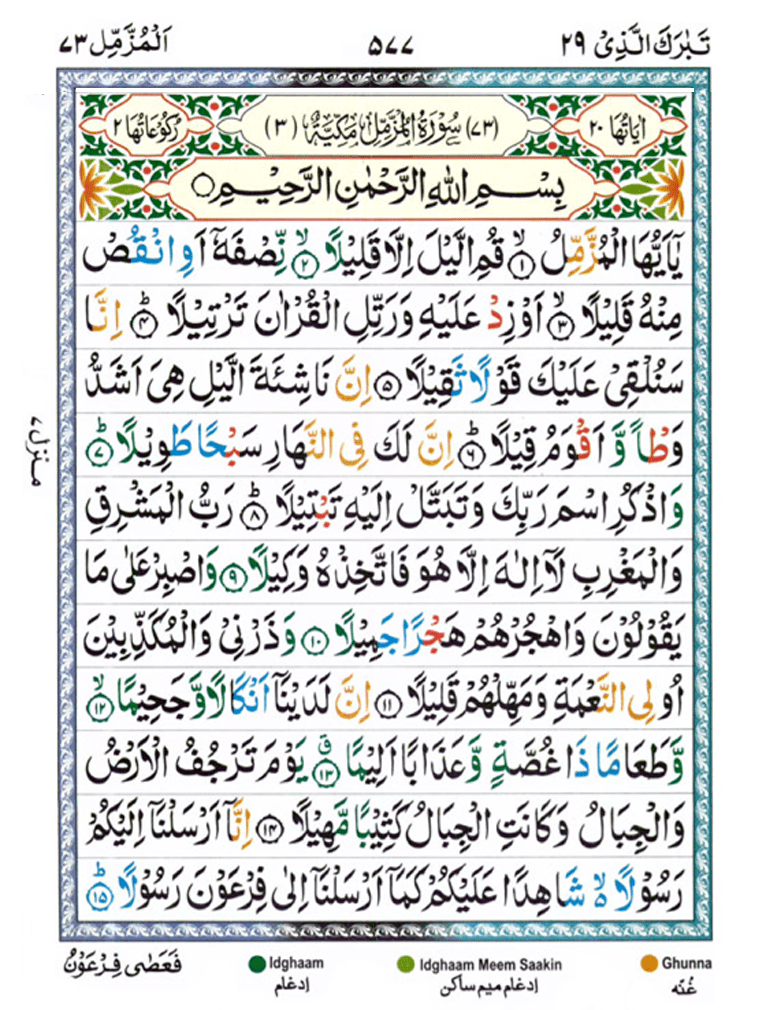

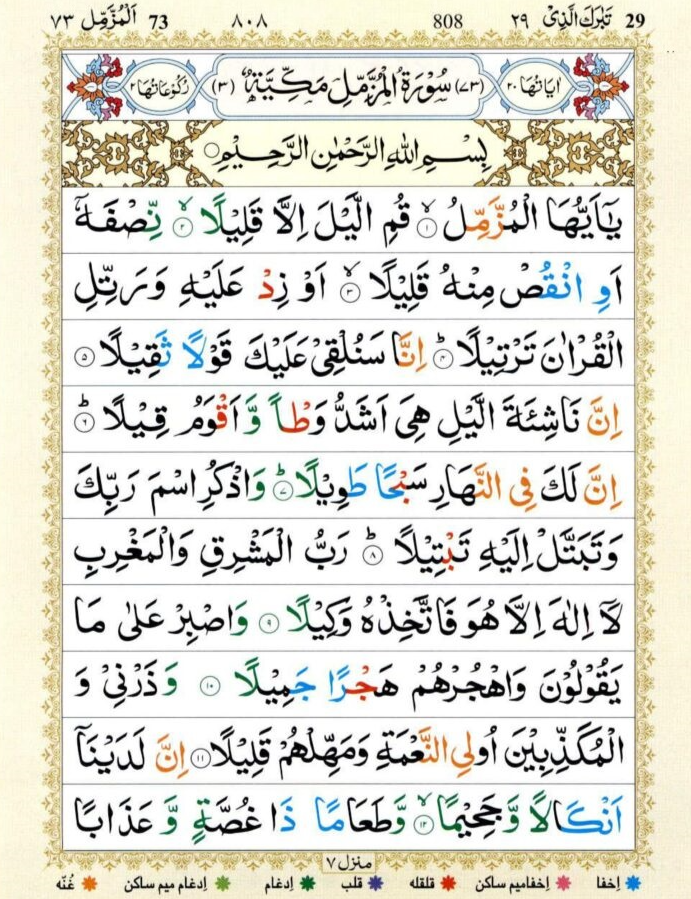

At the heart of Surah Al-Muzzammil, particularly verse 73:10, lies a powerful testament to divine compassion, social responsibility, and spiritual reciprocity. This verse, nestled within one of the most theologically rich chapters of the Quran, addresses the moral weight embedded in human relationships—especially between the powerful and the vulnerable. It speaks not only of material support but of the sacred bond forged through shared dignity and mutual obligation.

Through a careful examination of the linguistic nuances, historical context, and theological implications, Surah Al-Muzzammil’s 73rd verse reveals profound insights into Islamic ethics, emphasizing that protection and provision are not mere duties, but covenants undergirded by faith and accountability.

In Arabic, Surah Al-Muzzammil opens with the word "Al-muzzammil"—meaning “the one wrapped or mantled,” often interpreted as “the shielded” or “the one protected.” But beyond its literal portrait, the verse intensifies the meaning through the imperative: “Give to the guarantor what is owed, and to the captive justice.” This dual insistence—on paying a guarantor’s due and securing justice for captives—frames a principle of equity that resonates across time and cultures. The guarantor, historically a figure holding responsibility for another’s safety and reputation, becomes a symbol of trust in communal life.

Paying into their rightful security is not transactional; it is ethical and spiritual, reinforcing the idea that societal harmony depends on upholding fairness for all, particularly those stripped of agency.

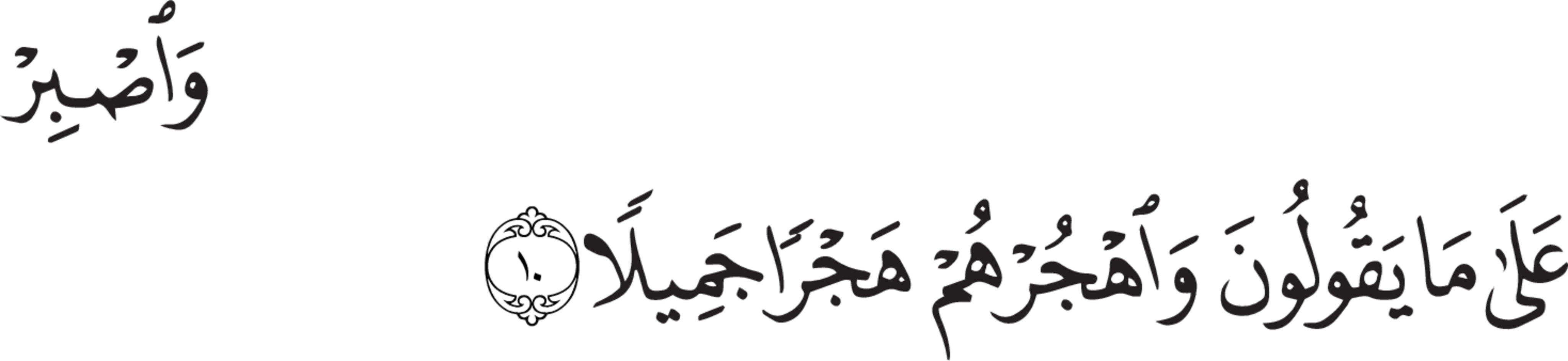

The Linguistic and Structural Strength of 73:10

The verse’s concise yet dense language packs layered meanings. The verb structure—“give to the guarantor what is owed, and to the captive justice”—reflects a deliberate prioritization: honor the responsibility of the protector, then restore the dignity of the held (the captive). The Arabic root (ʿ-ḍ-ḍ-m-m) associated with wrapping or sheltering evokes protection, safety, and containment—metaphors that deepen the concept beyond financial restitution into moral closure.This linguistic precision ensures the verse anchors itself in both legal fairness and spiritual grace.

In classical tafsir, commentators emphasize that “guarantor” ( tuck al-ḥimāyah ) often refers to a tribal or societal safeguard, responsible not only for physical safety but also for upholding honor. Captives, meanwhile, are contextualized not as passive victims but as individuals whose human dignity must be restored.

The juxtaposition underscores a holistic vision of justice—protecting the protector and redeeming the held as a twin imperative of the social contract.

Historical Context: Righthand Support in Prophetic Era

Surah Al-Muzzammil, revealed in Mecca during a period when social fragmentation and tribal honor codes dominated daily life, speaks directly to these realities. The “guarantor” ( tuck ) would traditionally assume responsibility for a debtor or hostage, a role laden with risk and trust. In pre-Islamic Arabia, failure to honor such bonds often led to cycles of violence and vengeance.By mandating timely payment, the Quran interrupts this spiral—shifting accountability from personal vendetta to institutional justice. The requirement to “give what is owed” transforms obligation into a moral act of mercy.

For captives, the call for justice echoes early Islamic commitments to humane treatment.

While not requiring full legal equality by modern standards, the Quranic mandate intrinsically challenges exploitation and calls for restoration—echoed in later jurisprudence that emphasized fair ransom, humane capture, and reintegration over revenge. This verse thus functions not only as a call to immediate action but as a foundational ethical stone in the building of a compassionate community.

Widespread Theological and Legal Echoes

The principles in Surah Al-Muzzammil (73:10) permeate Islamic thought and legal traditions.Fiqh (jurisprudence) elaborates on what “justice” entails—timely restitution, mutual negotiation, and avoidance of excess. Hadith collections reinforce the virtue of fulfilling such duties, linking them not just to legal obligation but to spiritual reward. A well-documented hadith states: “The most merciful of people are those who are kind to guests, especially captives.” This tradition binds the verse’s injunctions to lived piety and social conduct.

Modern Islamic scholars often cite Al-Muzzammil as a cornerstone in discussions of economic justice, social welfare, and humanitarian ethics. The verse’s demand to “give to the guarantor” reinforces accountability in mutual agreements, while the call for “justice to the captive” informs contemporary Islamic advocacy for prisoner rights and conflict mediation. Its timeless relevance lies in its insistence that security and equity are non-negotiable pillars of just societies.

Moral Dimensions: Beyond Compliance to Conscience

While Surah Al-Muzzammil sets clear legal parameters, it elevates the act beyond mechanical obligation toward conscious moral engagement. Giving “what is owed” demands not just financial accuracy but honor—recognizing the guarantor’s role with dignity. Securing justice for captives requires active empathy, moving beyond mere legality to genuine compassion.This dual focus—on repayment and redemption—reflects a holistic Islamic view where duty and mercy coexist.

In personal practice, this verse invites Muslims to reflect on their own roles as guarantors and advocates. Are they upholding commitments with integrity?

Are they standing for justice, especially on behalf of those silenced or imprisoned? Its quiet urgency calls for humility, integrity, and action rooted in faith. In a world often defined by power imbalances and broken promises, Surah Al-Muzzammil (73:10) remains a compelling reminder: true protection and security emerge not from force alone, but from trust, responsibility, and steadfast justice.

The Enduring Legacy of Sacred Economics

Surah Al-Muzzammil’s 73:10 stands as a bridge between divine instruction and human behavior, reminding believers that faith translates into concrete, compassionate action. By insisting on the proper settlement of debts and the just treatment of captives, the verse embeds ethics within the fabric of daily life—making social responsibility not optional, but sacred. As both historical decree and timeless principle, it challenges societies to build systems where protection is honored, dignity is restored, and justice is not a distant ideal but a living practice.In these lines, the Quranic voice speaks with clarity, conviction, and enduring moral urgency.

Related Post

Unpacking Surah Al-Muzzammil (73:10): The Strength in Humility and Divine Protection

Unpacking Surah Al-Muzzammil (73:10): A Stomach-Sobbing Supplication for Solace and Strength

Unpacking Surah Al-Muzzammil (73:10): The Refuge of the مرتد and the Promise of Divine Mercy

Benson Boone Parents: Behind the Spotlight of a Rising Hollywood Sensation