What An Ionic Compound Is—The Electrically Charged Architects of Chemistry

What An Ionic Compound Is—The Electrically Charged Architects of Chemistry

Beyond the visible and tangible world lies a hidden realm where atoms bond not through covalent pairs or shared electrons, but through a far more dynamic force: ionic bonding. An ionic compound forms when one atom transfers one or more electrons to another, creating oppositely charged ions that attract each other with powerful electrostatic forces. This transformation defines not just molecular structure but also the behavior, properties, and very essence of countless materials essential to daily life—from the salt on a dinner table to the ceramics in high-tech devices.

Ionically combined substances act as conductors in concentrated electrolytes, resist high temperatures, and dissolve strategically in polar solvents, making them indispensable across industries ranging from pharmaceuticals to renewable energy.

How Ionic Compounds Are Born: The Dance of Atoms and Electrons

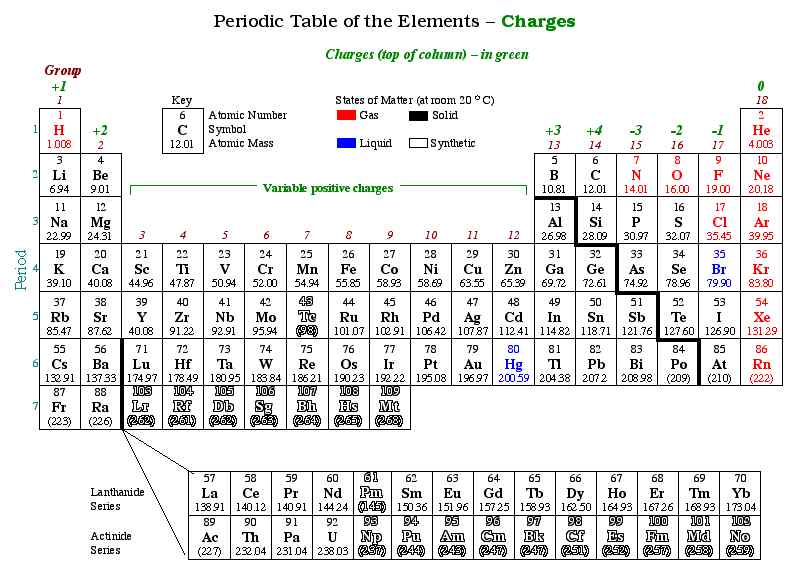

Ionic compounds originate in environments where metals and nonmetals interact under specific chemical conditions. Metals—naturally electron-rich—tend to lose electrons and become positively charged ions, known as cations.Meanwhile, nonmetals possess a strong reluctance to lose electrons but a high affinity to gain them, forming negatively charged anions. This electron transfer is not random but driven by the differing electronegativities between elements, as measured on the Pauling scale. When the energy required to excite valence electrons is overcome, whether through thermal energy, electrical current, or direct contact, ionic bonds stabilize.

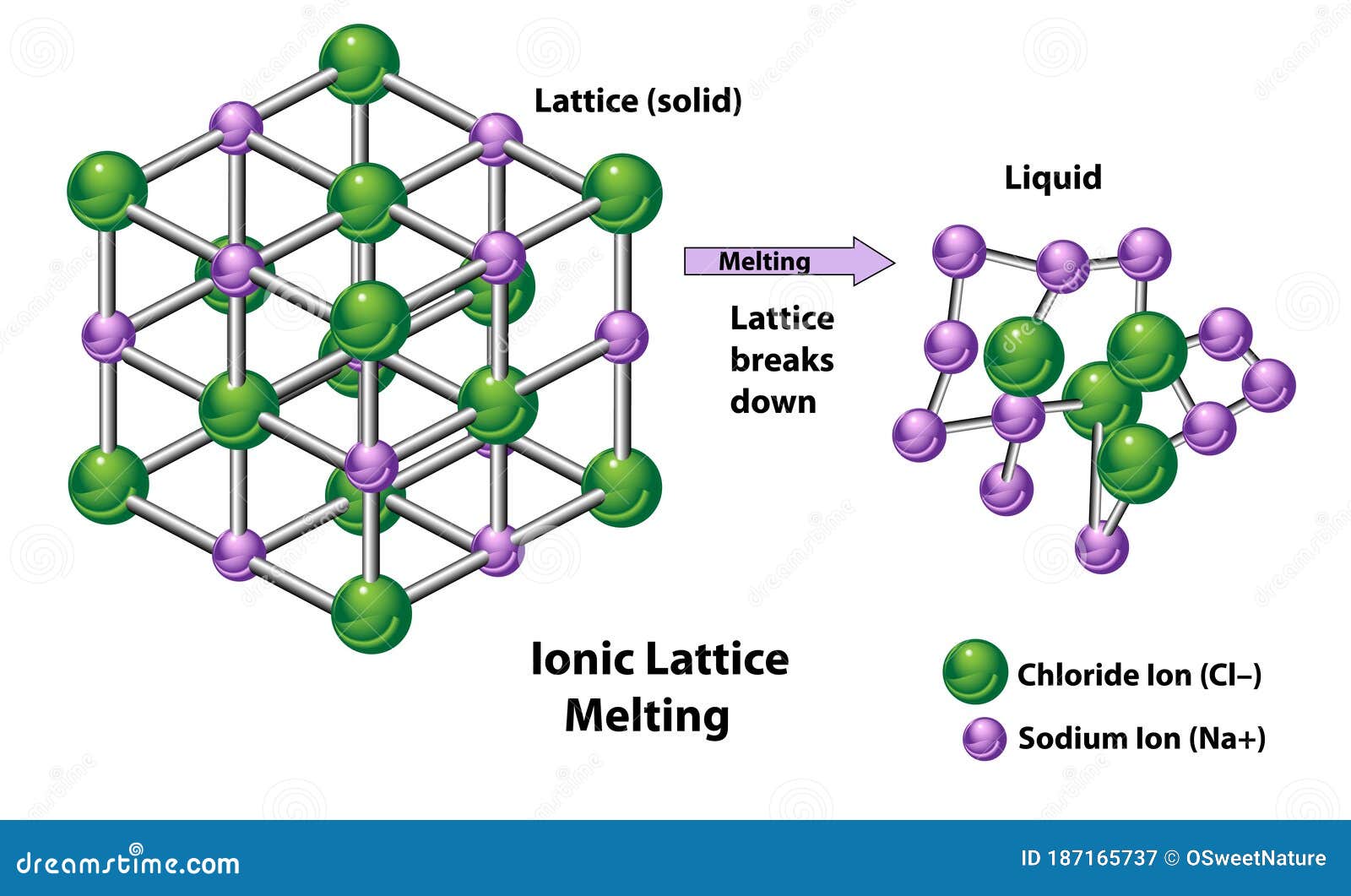

For example, sodium (Na), a highly electropositive metal, readily donates one electron upon contact with chlorine (Cl), a potent electronegative nonmetal. The resulting sodium cation (Na⁺) and chlorine anion (Cl⁻) arrange themselves in a repeating crystalline lattice optimized to maximize attractive forces while minimizing repulsive ones. This rigid, three-dimensional structure defines the stability of ionic compounds and explains why they often form hard, brittle crystals or brittle solids at room temperature.

The binding strength of ionic compounds hinges on Coulomb’s law: the electrostatic force between ions is proportional to the product of their charges and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. As a result, compounds composed of small, highly charged ions—such as magnesium oxide (MgO) or strontium carbonate (SrCO₃)—exhibit exceptionally high melting points, often exceeding 2000°C. This thermal resilience makes them ideal for refractory ceramics and industrial crucibles.

Routinely forming extended lattice networks, ionic compounds contrast sharply with molecular substances formed by covalent bonding. Their defining characteristic lies in electrical conductivity: in solid form, ionic compounds do not carry electricity due to fixed ions, but when dissolved in water or melted, they become potent conductors through ion mobility. This property underpins their critical role in biological systems—where electrolytes regulate nerve impulses and muscle contractions—and in technological applications such as batteries and fuel cells.

Physical and Chemical Properties: Foundation of Functionality

Ionic compounds manifest a distinct set of physical traits shaped by their lattice architecture.Their crystalline nature grants them sharp cleavage planes and brittleness—once a bond breaks along a lattice plane, adjacent layers shift and repel, vaporizing material rather than allowing deformation. This fragility limits mechanical flexibility but contributes to chemical durability in dry environments. Solubility is another hallmark behavior.

Ionic solids dissolve readily in polar solvents like water, where polar water molecules surround and stabilize individual ions through ion-dipole interactions. Sodium chloride, for instance, disperses effortlessly in aqueous solutions due to this mechanism, enabling its widespread use in food, medicine, and wastewater treatment. Thermal stability further defines their utility.

Their high lattice energies mean ionic compounds resist decomposition under moderate heat, making them reliable in applications from baking soda (NaHCO₃) in kitchen chemistry to refractory materials in steel furnaces. However, excessive thermal stress can fracture the lattice, breaking ionic bonds and leading to structural failure.

Everyday and Industrial Applications: From Table Salt to Solar Cells

Ionic compounds permeate modern life, their utility evident in countless products and processes.Calcium carbonate (CaCO₃), found in limestone and shells, reinforces construction materials and stabilizes soil pH. Potassium nitrate (KNO₃), historically used in fireworks and now in organic fertilizers, underscores ionic compounds’ dual role in technology and agriculture. In electronics, lithium cobalt oxide (LiCoO₂) enables energy storage in lithium-ion batteries

Related Post

Best Th9 War Base: The Ultimate Strategy Hub for Modern Battle Simulation

From Small Town Roots to Global Phenom: Thecomplete Masterclass Journey of Shohei Ohtani

Understanding The Dictator Saiyan: Power, Control, And Legacy

Charlie Kirks Smile A Closer Look: The Power Behind a Single Gesture in Leadership and Connection