What Is a Consumer in Science? The Key Players in Ecological Energy Flow

What Is a Consumer in Science? The Key Players in Ecological Energy Flow

From tiny zooplankton drifting through sun-drenched seas to apex predators roaming vast savannas, consumers in science represent a cornerstone of biological systems. In ecological study, a consumer is any organism that derives energy by ingesting other organisms, forming a vital link in the complex web of energy transfer across ecosystems. Unlike plants and algae—autotrophs that generate their own food through photosynthesis—consumers depend entirely on external sources, breaking down organic material for sustenance and driving nutrient cycling.

Understanding this role is essential to grasping how ecosystems function, evolve, and respond to change.

At the heart of ecological science lies the classification of organisms by their feeding strategies, with consumers occupying a dynamic and essential niche. Biologists define consumers based on their dietary habits and the organisms they consume.

The term encompasses a diverse array of species, subdivided fundamentally into three main categories: herbivores, carnivores, and omnivores. Each plays a distinct role in shaping ecosystem structure and energy flow.

The Three Pillars of Consumption: Herbivores, Carnivores, and Omnivores

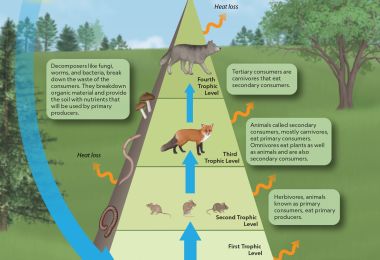

Herbivores, organisms that subsist predominantly on plant matter, initiate the transfer of solar energy stored in photosynthetic tissues. Together, they form the primary consumer level, converting sunlight indirectly harnessed through plant growth into biomass available to higher trophic levels."Grasshoppers on a meadow, finches on seeds—these are nature’s bridge between sunlight and complexity," observes ecologist Dr. Elena Torres. Examples include rabbits, elephants browsing acacia branches, and zooplankton feeding on algae.

Carnivores, by contrast, actively hunt and consume other animals. These consumers occupy secondary and tertiary levels in the food chain and are crucial in regulating prey populations. Their efficiency in energy transfer—though limited by trophic inefficiencies—underpins ecosystem stability.

Top carnivores, such as wolves in boreal forests or great white sharks in oceanic zones, exemplify apex consumers that maintain balance by preventing overpopulation and promoting biodiversity. Omnivores blur the boundaries between plant and animal feeding, eating both flora and fauna. This dietary flexibility enhances survival in variable environments.

Humans, bears, and many bird species like crows exemplify omnivorous behavior. Their dual consumption patterns make them pivotal connectors in food webs, capable of responding dynamically to resource availability.

Beyond these classical classifications, ecologists have identified specialized consumer roles that reflect adaptation to environmental niches.

Detritivores, such as earthworms and dung beetles, consume dead organic material, recycling nutrients and sustaining soil fertility. Parasitic consumers—like ticks, ticks, and tapeworms—derive sustenance at the expense of living hosts, illustrating a more parasitic form of consumption critical in population control. Each subtype reinforces the interdependence that defines ecosystem resilience.

Energy Flow and Trophic Efficiency: The Silent Drivers of Ecosystem Function

The movement of energy through consumers follows clear, quantifiable patterns.Ecologists quantify this through trophic levels—the vertical steps in the food chain—where energy declines at each ascending stage, typically by 80–90% due to metabolic loss, heat, and undigested matter. As a result, few organisms can feed on higher trophic levels; apex predators remain rare compared to herbivores, a pattern known as the ecological efficiency paradox. “Every bite of a honeybee’s nectar fuels a queen’s egg production, every salmon carcass nourishes forest soil—consumers are energy conduits with cascading influence,” explains Dr.

Malik Chen, a conservation biologist. This principle governs ecosystem productivity and stability, shaping species abundance, population cycles, and trophic cascades—echoes felt from field biologists in rainforests to oceanographers charting pelagic food webs.

Evolution and Coevolution: The Adaptive Arms Race Among Consumers

Over millions of years, consumers have evolved specialized traits optimized for catching, digesting, or navigating complex feeding strategies.Carnivores often evolve keen senses—binocular vision, acute hearing, swift agility—paired with teeth and claws adapted for killing or tearing. Herbivores counter with digestive adaptations such as multi-chambered stomachs in cows or coprophagy in rabbits, enabling efficient breakdown of cellulose. The predator-prey dynamic fuels an ongoing evolutionary arms race.

As prey evolve camouflage, speed, or defensive toxins, predators coadapt with enhanced detection or countermeasures. This reciprocal pressure drives biodiversity and functional complexity. For example, the peppered moth’s color shift during the industrial revolution exemplifies natural selection in response to environmental pressures, directly shaping consumer survival and ecological balance.

Human Influence and the Fragility of Consumer Networks

Human activity profoundly impacts consumer communities, destabilizing long-established ecological relationships. Habitat fragmentation disrupts migration routes of large carnivores like tigers and wolves, isolating populations and reducing genetic diversity. Overexploitation—through overfishing, poaching, or pesticide use—decimates key consumers, triggering trophic cascades.The collapse of sea otter populations, for instance, allowed sea urchin numbers to explode, decimating kelp forests and altering entire marine ecosystems. Yet, awareness of these consequences has spurred conservation efforts. Restoring apex consumers—reintroducing wolves to Yellowstone or protecting bats in tropical forests—has demonstrated ecosystem recovery and improved resilience.

Science now increasingly informs policy to preserve not just individual species, but the intricate networks of interaction that define ecological health.

In essence, consumers in science are far more than passive faith eaters—they are architects of energy flow, catalysts of evolution, and barometers of ecosystem integrity. From microscopic grazers to mighty predators, their roles are woven into the very fabric of life.

Understanding what a consumer is not only clarifies biological relationships but underscores the urgency of protecting the delicate balance sustaining our planet’s biological heritage.

Related Post

Unblocked The World’s Hardest Game: The Ultimate Test of Skill, Strategy, and Persistence

Brooke Taylor Fox: From Early Career Glimmers to National Spotlight — A Trajectory Built on Resilience and Vision

Example of Not a Function: The Case of Maximum in Set Theory

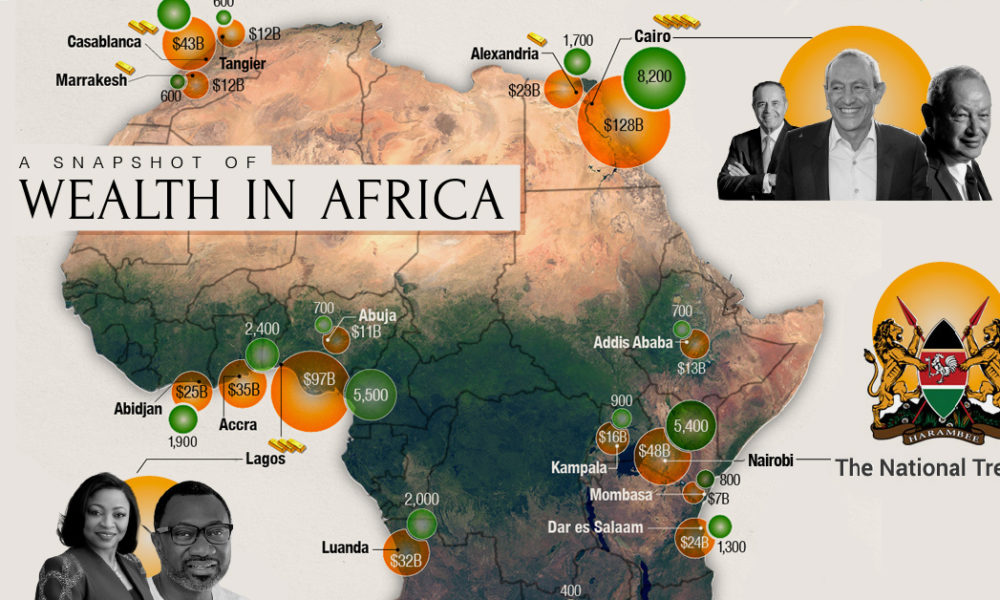

Top 10 Richest Nations: Where Global Wealth Concentrates in the Modern Economy