What Is Not Polynomial: Unraveling the Non-Polynomial in Mathematics

What Is Not Polynomial: Unraveling the Non-Polynomial in Mathematics

Polynomials form the backbone of algebra, underpinning everything from elementary equations to advanced calculus and computational algorithms. Yet, not everything that appears in mathematical models or computations follows this structured form. What is not polynomial reveals a rich, often overlooked landscape of functions and expressions that defy the traditional algebraic framework—challenging assumptions, complicating analysis, and expanding the frontiers of mathematical inquiry.

This article explores the defining characteristics of functions that resist polynomial classification, illustrating their roles across theory and real-world applications with precision and depth.

Defining the Boundaries: What Makes a Function Not Polynomial

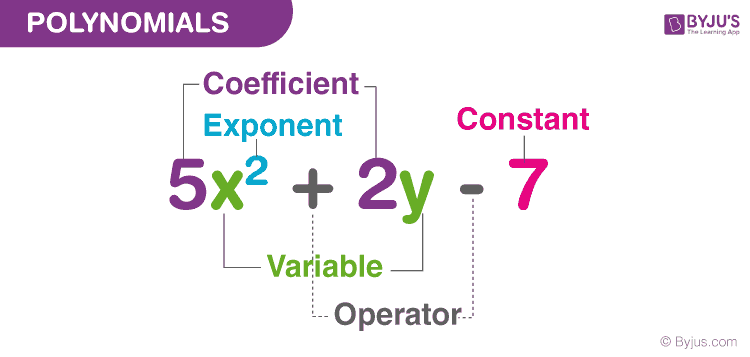

A polynomial function is defined by a finite sum of terms involving variables raised to non-negative integer exponents, combined through addition, subtraction, and multiplication. Example: $ P(x) = 4x^3 - 2x + 7 $. The non-polynomial realm encompasses anything that violates this core structure.These functions exhibit behaviors and complexities that polynomials cannot easily capture.

Several fundamental properties distinguish non-polynomial functions:

- Irrational and Transcendental Expressions: Functions involving constants like $ \pi $, $ e $, or $ \sqrt{2} $ in infinite or non-integer powers—such as $ \sin(x) $, $ e^x $, or $ x^{\sqrt{2}} $—fall outside polynomial space. Unlike polynomials with exponents restricted to $ 0, 1, 2, \ldots $, these transcend elementary algebraic closure.

- Infinite Series and Continuity Issues: Series expansions such as $ \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-1)^n x^{2n}}{(2n)!} = \cos(x) $ converge over entire intervals but include infinitely many monomials, making cosine not a polynomial despite polynomial-like local behavior.

- Exponential and Logarithmic Growth: Functions like $ a^x $ with $ a > 0, a \ne 1 $ stretch across exponential domains, showing growth or decay fundamentally incompatible with finite-degree polynomials.

- Non-algebraic and Transcendental Functions: Examples include the error function $ \text{erf}(x) $, the logarithmic integral $ \text{Li}(x) $, and fractional exponents such as $ x^{1/3} $ in unrestricted domains.

This divergence forms a conceptual fault line in mathematics: polynomials offer predictability and computability, while non-polynomial functions often encode dynamic, chaotic, or irregular phenomena essential to physics, engineering, and data science.

Key Catalogs: Functions That Stand Apart

The non-polynomial universe houses several canonical classes of functions, each with defining features that resist algebraic simplification.Transcendental Functions and Their Indelible Mark

Transcendental functions are perhaps the most prominent non-polynomial constructs. They include trigonometric functions (e.g., $ \sin(x), \cos(x) $), exponential functions ($ e^x $), logarithmic functions ($ \ln(x) $), and hyperbolic analogs. Unlike algebraic polynomials, they lack roots expressible in radicals and exhibit non-repeating, non-algebraic behavior across domains.The logarithm $ \log(x) $, for example, grows slowly yet infinitely—unlike any finite-degree term—and cannot be represented as a sum of monomials.

Hypergeometric and Special Functions Adding to this lineage are special functions like the Riemann zeta function $ \zeta(s) $ or Bessel functions $ J_n(x) $, which arise in number theory and differential equations. Though vital in solving Laplace’s equation, quantum mechanics, and vibration modes, their infinite series expansions and special convergence properties exclude them from polynomial classification.

These functions embody mathematical depth but require entirely different analytical tools to manage.

Rational and Algebraic but Non-Polynomial Constructs

Not all non-polynomials are transcendental. Rational functions — ratios of polynomials — are often mistaken for algebraic, but the broader category includes non-polynomial rational expressions like $ \frac{x^2 + 1}{x - 3} $. Even algebraic functions, defined implicitly through polynomial equations (e.g., $ x^3 - 2x + 1 = 0 $), extend beyond polynomials by introducing roots and multivalued constructs.When generalized, such roots introduce infinitely many potential inputs for each output, destabilizing finite-degree modeling.

The Hidden Complexity in Real-World Systems

In applied mathematics, non-polynomial functions are indispensable. Consider heat transfer governed by the heat equation, solved using $ e^{-kt} \sin(nx) $—a transcendental solution not a polynomial. Similarly, wave propagation, electrical circuit analysis, and signal processing depend on exponential decay and oscillation modeled by $ e^{-\alpha t} \cos(\omega t) $.In statistics, probability density functions involving empirical risks or nonparametric densities frequently adopt smooth but non-polynomial forms like Gaussian kernels or logistic curves.

These real-world dependencies underscore a key insight: polynomials model simplicity; non-polynomials capture complexity. Their refusal to collapse into sum rules and finite monomials reflects the rich, often chaotic nature of physical and digital systems.

Classification and Mathematical Hierarchy

Mathematicians distinguish functions rigorously through algebraic and analytic hierarchies.Polynomials occupy the foundational tier, easily defined, differentiated continuously, and integrated neatly. Functions stepping beyond this threshold fall into broader categories: analytic, differential, or transcendental. Non-polynomial functions—irrational, series-based, or tied to transcendental constants—reside at the upper tiers

Related Post

Nasdaq Symbols: The Pulse of Innovation and Market Momentum

Top Android Emulators: Your Guide To Mobile Gaming—Access Your Apps Anywhere

Unlocking the Digital Frontier: How Kat Cr Proxy Lists Bypass Internet Blockages and Restore Free Access

Shiva Negar: The Rising Star of Heartland’s Agricultural Renaissance