WhatIsTheSectionalism? Unraveling the Deep Divide That Shaped a Nation

WhatIsTheSectionalism? Unraveling the Deep Divide That Shaped a Nation

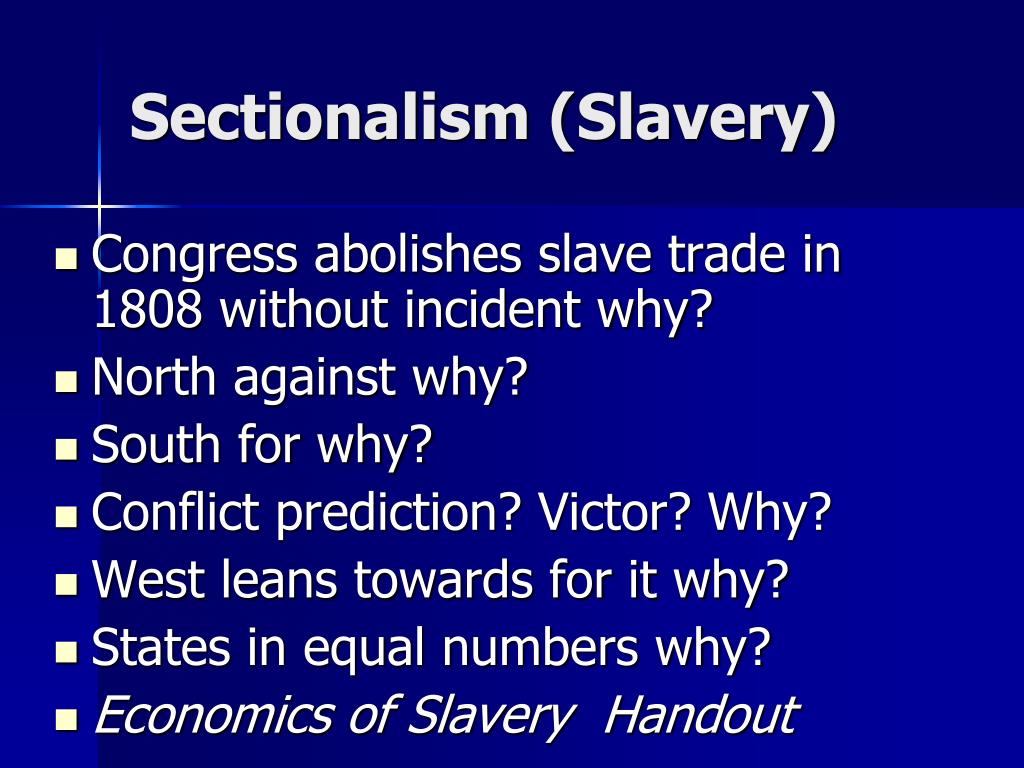

Sectionalism—the intense loyalty to one’s regional section, often at the expense of national unity—was a driving force in 19th-century American politics, culminating most dramatically in the crisis that led to the Civil War. Far more than a cultural or economic difference, sectionalism reflected fundamental conflicts over slavery, states’ rights, economic systems, and political representation that fractured the young republic’s cohesion across four decades. This article examines the roots, key phases, and lasting consequences of sectionalism, revealing how regional identities overpowered national identity and reshaped the course of U.S.

history. What is Sectionalism? Sectionalism denotes a powerful allegiance to one geographic region, entwined with distinct economic interests, political ideologies, and social values.

In antebellum America, two dominant sections emerged: the industrial, abolitionist-leaning North and the agrarian, slave-based South. Each developed unique economic systems—manufacturing and commerce in the North versus plantation agriculture and cotton exports in the South—creating divergent worldviews. These differences were not merely economic but ideological, challenging shared national principles.

As historian David Blight notes, “Sectionalism revealed how geography, race, and economic life fused into a battle over the soul of America.”

Historical Foundations: From Compromise to Conflict

The origins of sectionalism stretch back to the nation’s founding, but it intensified during westward expansion in the early 1800s. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 marked an early attempt at containment, admitting Missouri as a slave state and banning slavery north of the 36°30' parallel. Yet, each new territory reignited the struggle: Texas annexation, the Mexican-American War, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 reignited violence and political polarization.The principle of “popular sovereignty,” which allowed settlers to decide slavery’s fate, backfired spectacularly, triggering bloody conflict in Bleeding Kansas and exposing how regional interests overrode constitutional compromise.

Economic Foundations and Diverging Identities

The North’s rapid industrialization transformed cities into hubs of factories, railroads, and wage labor, fostering a diverse, urban economy dependent on free labor. In contrast, Southern wealth was rooted in cash crops—especially cotton—dependent on enslaved people. By 1860, Southern elites argued secession was inevitable if federal power threatened their “{\em’peculiar institution’}.” As Southern economist James heritage Frederick Douglass observed, “Our industry, your plantations—the South’s lifeblood and your moral crisis.” This economic divergence fed political distrust: each region viewed the other as not just ideologically opposed but economically incompatible, solidifying sectional identities.Political Exploitation and the Rise of Regional Blocs

Sectionalism thrived not only through culture and economy but through political maneuvering. The Democratic Party fragmented along sectional lines, with Northern Democrats increasingly aligned with anti-expansion sentiment, while Southern Democrats demanded protection of slavery in new territories. The formation of the Republican Party in 1854—opposing slavery’s expansion—marked a pivotal shift.Its platform appealed to Northern protestants, free labor advocates, and anti-slavery expansionists, creating a new sectional political bloc. By 1860, the election of Abraham Lincoln, a Republican from Illinois, triggered secession, proving that political loyalty had supplanted loyalty to the Union.

Key Events That Radicalized Sectional Tensions

Several pivotal moments deepened sectional mutual suspicion. The 1857 Dred Scott decision shocked the North, ruling that Black people—free or enslaved—were not U.S.citizens, fueling accusations that the South manipulated the courts to spread slavery. Meanwhile, John Brown’s 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry, meant to spark a slave rebellion, was seen in the South as proof of Northern aggression. These events, combined with profit-driven failures like the Nullification Crisis and debates over tariffs, ensured that compromise became impossible.

The regional fault lines were no longer masked by national institutions—they were exposed in blood, property, and ideology.

Lingering Shadows: The Legacy of Sectionalism in American Life

The Civil War (1861–1865) ended formal secession and slavery, but sectional divisions left lasting scars. Reconstruction deepened mistrust in Southern states, where resistance to federal oversight persisted through Jim Crow laws.Economically, the South’s agrarian model stagnated compared to the North’s industrial boom, creating regional inequality that endured well into the 20th century. Culturally, memories of the “Lost Cause” mythology perpetuated sectional nostalgia, complicating national reconciliation. Today, subtle hints of regional identity remain—from political alignments to economic disparities—reminding Americans of how deeply sectionalism shaped—and continues to influence—the nation’s evolving identity.

Sectionalism was not just a historical phenomenon but a foundational struggle over American unity. It revealed how regional loyalty, when fused with economic dependence and moral contradiction over slavery, could fracture a nation. Understanding what constituteeth theSectionalism illuminates not only the path to civil war but ongoing debates about diversity, federalism, and national cohesion.

Far from a relic of the past, Sectionalism endures as a cautionary story of how regional identities, left unchecked, can undermine shared destiny.

Related Post

IHaveNoMouthAndIMustScreamPdf

Miriam Hernandez Redefines Leadership in Public Service: A Trailblazing Force Across Policy and Community Impact

James Harden Beard: A Clean-Shaven Icon Who Redefined Masculine Style in Basketball

Detroit Lions vs Chicago Bears: A Clash of Speed and Strength Measured in Stats