Who Stood Before the Silent Guardian? Decoding the Sphinx’s Riddles in the Odyssey

Who Stood Before the Silent Guardian? Decoding the Sphinx’s Riddles in the Odyssey

In the timeless shadow of ancient myth, the Sphinx of Greek lore stands as one of the most imposing and enigmatic figures of the ancient world—its riddle a psychological and linguistic trial that tested not just wit, but the very essence of human identity. Central to this legend are the perilous riddles posed to travelers who dared approach Thebes, where the Sphinx’ immobilizing presence guarded the city’s threshold. Among these, the most celebrated is the one that earned her immortal curse: “What walks on four legs in the morning, two at noon, and three in the evening?” This riddle, rich in metaphor and layered meaning, invites endless interpretation, while also revealing the intricate cultural fabric woven into Homer’s *Odyssey* and the broader classical tradition.

The Sphinx’ riddles were more than mere puzzles—they were trials of wisdom, early metaphysical reflections, and symbolic gateways between mortal certainty and divine insight.

The Sphinx’ riddle—“What walks on four legs in the morning, two legs at noon, and three in the evening?”—has fascinated scholars, poets, and adventurers for millennia. Its simplicity cloaks a profound duality rooted in the human life cycle: a quadruped representing infancy, bipedal adulthood at midlife, and a three-legged figure symbolizing old age.

This tripartite structure reflects ancient Near Eastern and Mediterranean symbolism, drawing on the metaphor of walking as a life progression. As expressed in Homeric tradition, each stage mirrors a phase of human destiny: dependently clinging to support, achieving balance, and eventually relying on guidance. The riddle’s phrasing belies philosophical depth: the riddler must grasp not just the biological journey, but the symbolic arc of transformation.

In later traditions, this passage became synonymous with rite-of-passage trials—symbolizing wisdom won through introspection and experience rather than brute force or luck. It reflects a core Greek insight: that true knowledge emerges through the complex interplay of time, strength, and maturity.

Within the epic *Odyssey*, although Odysseus himself does not face the Sphinx directly—she resides in Thebes, while Odysseus traverses the wider Mediterranean—her riddle exerts a pervasive influence.

The poem's civilization-wide reverence for such enigmas underscores a shared Greek preoccupation with cunning, fate, and the limits of mortal understanding. Like Odysseus’ labors, the Sphinx’ challenge demanded more than clever deduction; it required moral and intellectual alignment with deeper cosmic truths. The sphinx thus embodies the tension between hubris and humility—posing questions only solvable by those who recognize human frailty and divine design.

The Life Cycle Metaphor: Life Stages Encoded in Motion

The Sphinx’s riddle hinges on the universal metaphor of movement through life, articulated through physical posture. Early in life, humans crawl—on four limbs—a stage of dependence and vulnerability. As adults, they stand upright, a posture symbolizing stability and purpose—a phase defined by mobility in two “legs,” representing societal roles.By old age, most adopt a cane, adopting a three-legged gait that symbolizes wisdom earned through experience, slowed but grounded. This progression is not merely biological but moral and spiritual: each phase demands a different kind of strength. Scholars note parallels in Egyptian and Mesopotamian iconography, where deities and kings are depicted in characteristic three-legged forms during representations of aging or divine authority.

Such symbolism transcends Greek culture, pointing to a shared ancient understanding of life’s arc as cyclical and layered. The riddle, therefore, serves as a compact allegory, teaching that maturity lies not in youthful vigor but in reflective wisdom—qualities Odysseus himself embodies through his long journey.

Linguistically, the riddle’s power lies in its deliberate brevity and dual meaning.

The Greek phrase *πηλαίη ἣ δύνη* (“walks on four legs in the morning”) subtly merges literal description with metaphor, relying on the reader’s intuitive leap from physical position to existential stages. Ancient sources, including Pausanias and later Greek grammarians, highlight how this riddle’s enduring appeal springs from its ability to provoke both logical and philosophical engagement.

The Riddle in Classical Interpretation and Beyond

Throughout antiquity, the Sphinx’s riddle was treated not just as a mythic test, but as a cultural touchstone.Plato references similar cryptic dialogues in *The Republic*, using riddles to guide soul-searching toward eternal truths. The Sphinx thus becomes emblematic of the Socratic method—where questioning unlocks deeper understanding. Even in Roman literature, Ovid and Seneca echo the motif, reinforcing the idea that profound wisdom often resides in paradox and indirect inquiry.

In archaic and classical Greece, such riddles were embedded in rituals, initiation rites, and civic identity. Hours spent solving them in assembly or educational gymnasia cultivated collective wisdom, linking individual insight with communal values. The Sphinx, in this context, was not merely a monster but a symbol: balancing guardianship with transformation, isolation with revelation.

Modern analysis, drawing from comparative mythology, linguistics, and psychology, reveals layers of meaning often obscured by time. Some scholars interpret the riddle’s “three legs” as a metaphor for past, present, and future selves

Related Post

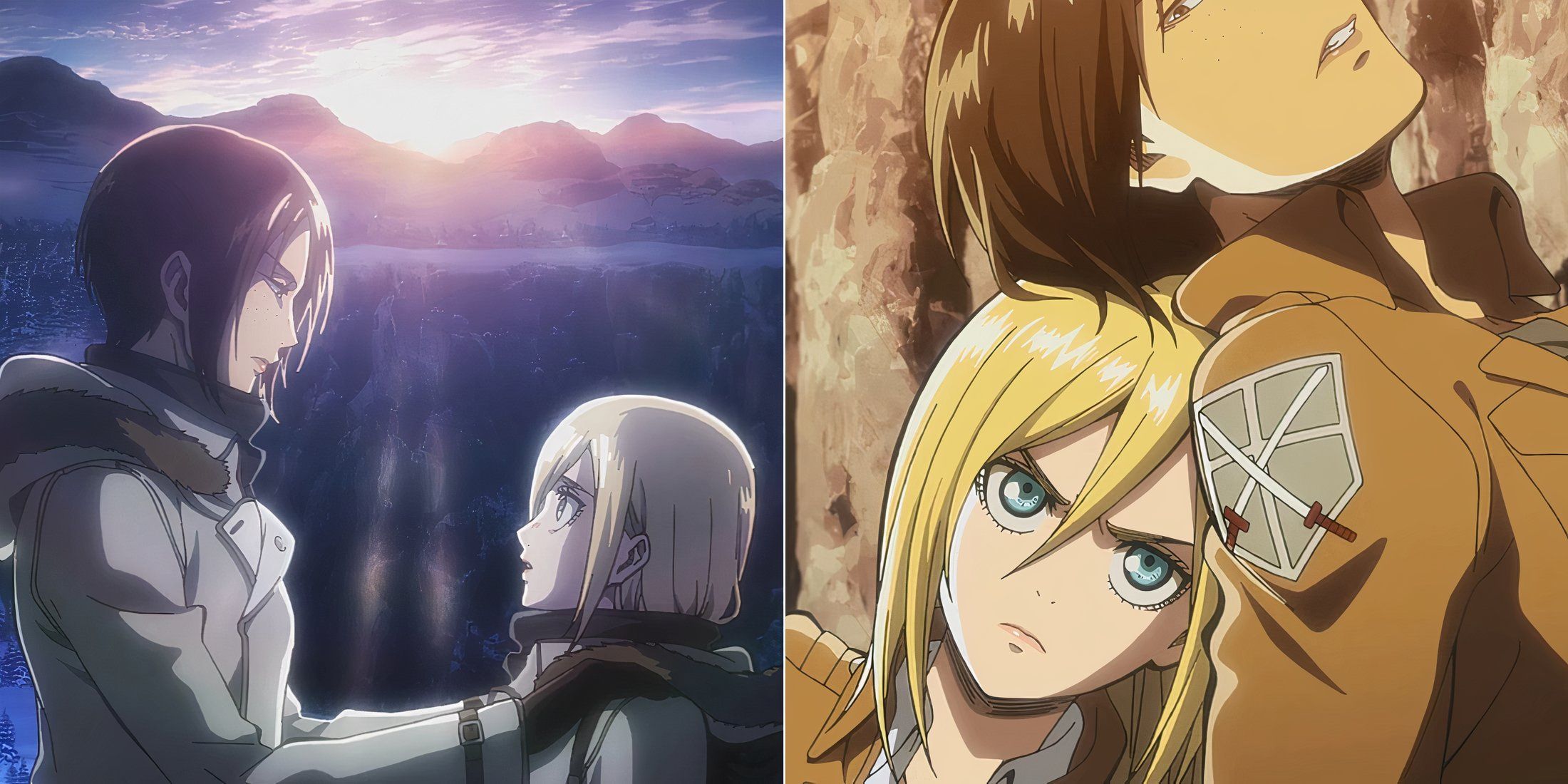

Unlocking the Secrets of Aot Ymir: The Ancient Catalyst Reshaping Modern Innovation

Pami Baby ED: How Early Development Shapes Lifelong Child Growth

Tyler James Williams: Age, Height, Wife, and the Trace of a Rising Star

Unlock the Power of Admirer By Aden: Your Ultimate MP3 Download Guide