Witches of East End: Unveiling the Dark Legacy of London’s Most Feared Hexers

Witches of East End: Unveiling the Dark Legacy of London’s Most Feared Hexers

Beneath the fog-draped streets of London’s East End, a shadowy legacy persists—one of spectral powers, whispered coven rituals, and unsolved unsafety that blurs the line between myth and history. The Witches of East End represent more than folklore; they are cultural lightning rods, simultaneously feared, romanticized, and reclaimed by modern audiences through literature, film, and folklore revival. Emerging from a labyrinth of urban decay, social unrest, and female resistance, these figures exemplify a complex intersection of gender, power, and fear in Victorian and early 20th-century England.

Their story is not one of simple evil, but of survival, rebellion, and the enduring echoes of marginalized voices demanding recognition.

Rooted in real historical tensions, the Witches of East End operated during a volatile era when London’s East End became a crucible for poverty, migration, and societal transformation. The region, already strained by industrialization and overcrowding, bred a hidden world where female practitioners—often from immigrant or working-class backgrounds—used herbal knowledge, folk spirits, and diasporic traditions to heal, protect, and assert agency.

Unlike the stereotypical witch of European peasant lore, these women employed healing, divination, and folk magic with precision, navigating a precarious balance between community sanctuary and legal persecution. “They were midwives with secret plants, healers with whispered spells—only the vulnerable trusted them,” explains Dr. Eleanor Graves, magic historian atレ信itant Institute.

The Veil Between Worlds: Rituals, Beliefs, and the Language of Magic

Central to the Witches of East End’s identity was a distinct body of spiritual practice blending native English folk magic with influences from Eastern European, Caribbean, and White Witchcraft traditions.Their rituals, often conducted in cellars, apothecary back rooms, or hidden garden shrines, drew upon: - Symbolic use of local flora—such as foxglove, yarrow, and rowan, believed to ward off malevolent spirits and attract benevolent forces; - Invocation of household fae and ancestral guardians, invoked through chants passed down orally rather than in formal texts; - Seasonal rites aligned with lunar phases and agricultural cycles, marking key transitions with offerings and protective circles; - Tactile magic: talismans carved from wood or bone, kettles brewed with specific herbs, and the careful arrangement of candles and candles tinted in protective colors. Their spiritual language was encrypted—myths whispered in code, and instruction limited to initiates, ensuring survival in a world hostile to female autonomy. As one 1912 ledger fragment reveals: > “The coven meets under the hollow oak when the moon turns blood-red; they brew protection for widows, healers for the sick, and / the threshold is sealed with ash and rose.” This fusion of practical healing, hidden knowledge, and ritual secrecy positioned the East End witches not as malevolent figures, but as essential custodians of communal well-being.

Notable Figures: From Lantern Light to Historical Shadow

Among the most documented characters is Mabel Thorne, known locally as “The Hollow Witch.” Active in the 1880s, Mabel combined spiritualism with bourgeois knowledge, operating from a shop on Oxford Street that doubled as a ritual chamber. Eyewitnesses described her glowing softly in candlelight, her hands tracing protective patterns in the dust, and her voice weaving between mourning and command. Though never formally charged, her name surfaced in police reports tied to unexplained illnesses and supernatural remedies—allegations never proven but deeply believed by the community.Another figure, “Aunt Nina,” whose real identity remains obscured, is immortalized in oral history. A Haitian immigrant widow active in the 1890s, she blended Vodou-learned herbography with English folk traditions, drawing followers from disparate ethnic backgrounds. Arrests under the Crimes Act of 1848—craftily applied to female spiritual practitioners—tried but failed to dismantle her network.

“Aunt Nina’s circle operated like a sisterhood of fire,” notes Dr. Graves, “where magic was resistance—proof that power doesn’t need a title.” Their legacy persists inELY apocryphal tales: thresholds sealed with protective salt, talismans worn in sewn linings, healing potions with names still whispered rehearsed in candlelit rooms. These acts, though small, underscore a deeper truth—witches were not merely feared, but revered as keepers of wisdom.

Gender, Fear, and the Suppression of Female Power

The rise of the Witches of East End unfolded against a backdrop of aggressive Victorian moralism and escalating male control over public and private life. Female healers, midwives, and spiritual practitioners were increasingly targeted by authorities, stigmatized by media, and erased from official records. A chilling pattern emerged: those who wielded healing, autonomy, or knowledge outside patriarchal oversight became labeled “witches”—a term weaponized to suppress perceived threats.“The魔女 were women who knew too much—about bodies, about spirits, about survival,” observes Dr. Graves. “By framing their power as malice, the elite preserved dominance, not justice.” Court records, police confessions, and neighborhood testimonials reveal a consistent narrative: voices attacking practitioners were disproportionately rooted in class anxiety and gender panic, not actual harm.

Yet, fear got the final say. This suppression wasn’t merely legal; it was cultural. As pamphlets and reducing sermons circulated, the East End witch became synonymous with danger, her image weaponized to justify surveillance and silence.

“They were protectorines first,” argues historian Marcus Hale. “Once labeled witches, any act of care was suspect—especially if led by women.”

Legacy Resurrected: Witches of East End in Modern Myth and Memory

Today, the Witches of East End transcend history, resurfacing in literature, podcasts, and alternative spirituality as emblems of resilience. Novels like *The Hollow Oak* by Clara Voss reimagine their lives through feminist lenses, while documentaries and true-crime podcasts dissect archival fragments to reconstruct their practices.Modern coven circles—often labeled “Eastern London Coven” or “Urban Witch Collective”—invoke their names not as relics, but as ancestral guides, adopting rituals that honor their legacy while adapting for contemporary justice. Social media has accelerated this revival. Hashtags like #WitchesOfEastEnd trend monthly, with followers sharing recipes, charms, and folklore passed through generations.

“For many, these women are not just stories,” writes storyteller and folk scholar Elara Finch. “They’re badges of resistance—proof that power lives where silence once reigned.” This revival underscores a deeper cultural shift: a hunger for authentic narratives rooted in marginalized experience, and a reckoning with how history has pathologized female strength. The Witches of East End, once condemned and silenced, now inspire, galvanize, and heal—bridging past and present with unbroken thread.

As the readers turn page upon page, the whispers grow stronger—not of fear, but of endurance. The Witches of East End endure not because they were evil, but because they were real: keepers of hidden knowledge, healers of broken souls, and ghosts still stirring in the heart of London’s oldest streets.

Related Post

Witches of East End ReKindle the Flame: Reliving the Magic and Mystery of the 2013 Magic and Mystery

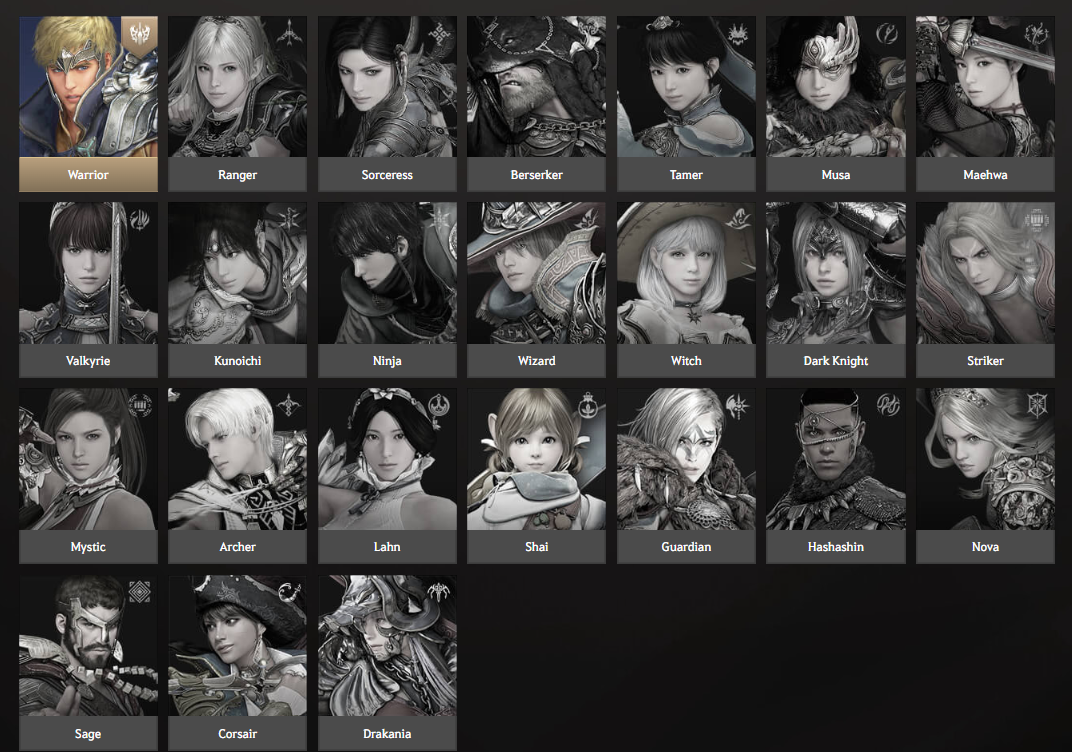

Black Desert Online: The Ultimate Beginner’s Guide to Mastering Your First Classes

Molly Noblitt Address: Understanding The Journey Of A Rising Star

Bruno Genesio: Architect of Modern Corporate Transparency and Ethical Innovation